Table of Contents

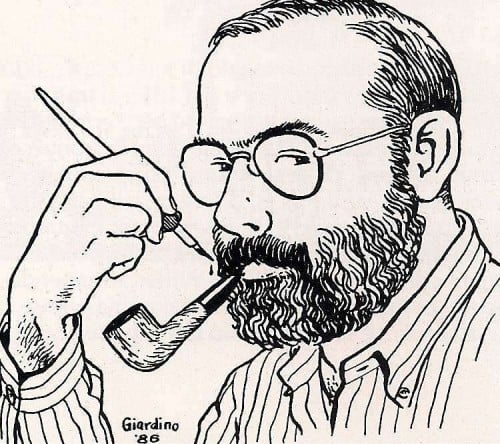

The life and works of Vittorio Giardino, the ligne claire maestro considered Italy’s most sophisticated comics artist.

Born in Bologna in 1946, Vittorio Giardino is widely regarded as a master of comics, both in his native Italy and abroad. Inspired by ligne claire, his elegant style is more than just a drawing technique, it’s a visual language for exploring complex political, social and psychological themes.

From Sam Pezzo to Max Fridman, Giardino tells gripping tales that interweave personal lives with historical events. His own story is unusual: he worked as an engineer for many years before making a living as a cartoonist. Over a long and successful career in comics, he has won numerous awards, including a Yellow Kid for Hungarian Rhapsody and Harvey and Alfred awards for Jonas Fink.

We look back at the life and works of this extraordinary Italian artist.

From engineer to cartoonist

The Giardino family did not come from the art world, although they did value culture and learning. After finishing school, Vittorio went on to study engineering, but his true love was reading and drawing comics.

As a kid, he devoured Disney comics such as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. Indeed, Carl Barks and Floyd Gottfredson would be huge influences on his own work. Then, as he approached adulthood, Giardino discovered Linus magazine and the more grown-up and high-brow comics inside.

Reading Hugo Pratt, Guido Ceppa, Philippe Druillet and Moebius in its pages, Giardino realised that comics could tell complex stories to adult audiences, and soon graduated to the works of José Muñoz and Jacques Tardi.

Although he never formally studied art, Giardino has always been minded towards precision and perfection, qualities that shine through in his drawing style. After receiving a degree in electronic engineering, he duly began a career in the field, but his passion for drawing remained undimmed.

Which is why, in 1979, now in his early thirties, married and father to two little girls, he decided to pack in engineering and dedicate himself to creating comics full time. A decision he later said was “tantamount to suicide” and “completely reckless” (despite having family to fall back on if things didn’t work out), because he knew nothing about making a living from comics art.

Of course, there was no internet in the seventies, but there was pirate radio. And Giardino was an avid listener to a comics show presented by Luigi Bernardi, a prominent writer and critic in Bologna. Through Bernardi’s broadcasts, Giardini got a crash course on the comics business.

Despite his science background, Giardino quickly learnt the language of comics, drawing on his technical skills to develop a clear and precise storytelling style. His engineering experience also helped him compose panels that are perfectly structured and balanced, but leave space for artistic expression.

Early works and Sam Pezzo

Vittorio Giardino was completely self-taught: having never studied art, he instead honed his craft alone, feeding what he called his “addiction to drawing”.

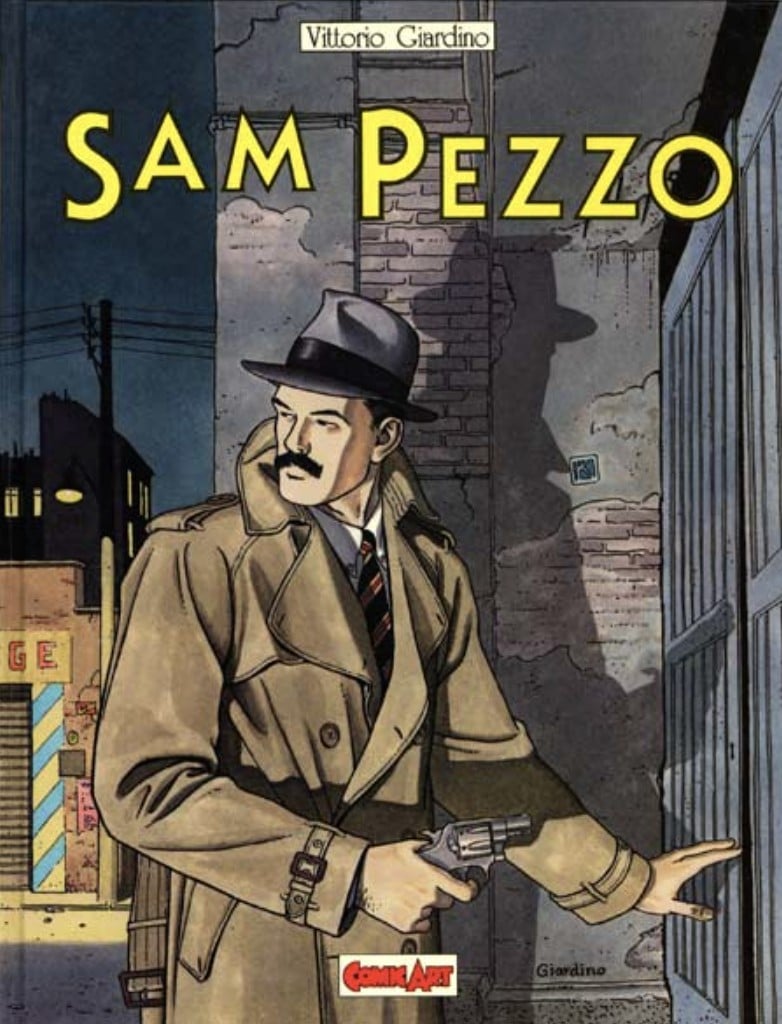

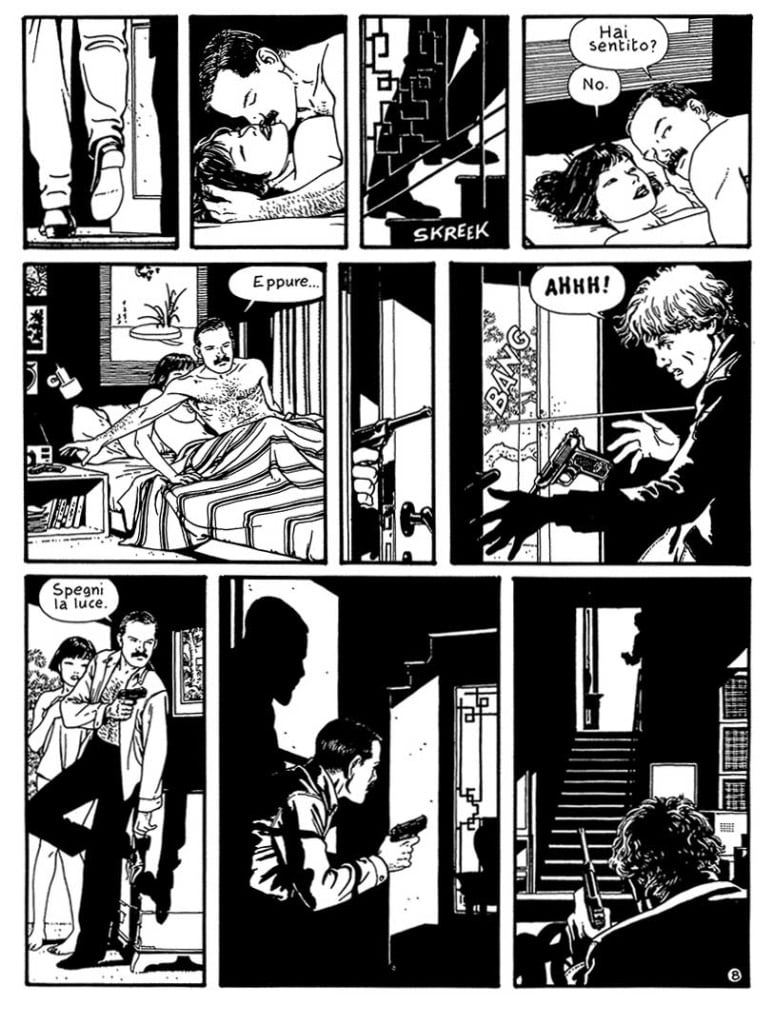

He began by publishing pieces in fanzines and independent magazines, before getting his big break in Il Mago magazine with his first character, Sam Pezzo. At turns funny and poignant, this black and white comic follows the hard-boiled adventures of the titular private investigator in a city that is never named, but clearly resembles Bologna.

Sam Pezzo stories were published in Il Mago until 1980, before switching to Orient Express from 1982 to 1983. In his first published work, Giardino displays a flair for storytelling and an obvious debt to Raymond Chandler. He makes effective use of black shading to create a noir atmosphere, but, unsurprisingly, his penwork is not quite as polished as it would be in his later output.

Over the years, the Sam Pezzo series allowed Giardino to refine his style, his penwork becoming softer but never static.

The series was also a testing ground for experiments in storytelling through powerful panels. And it showcased not just Giardino’s drawing skills, but his knack for constructing compelling plotlines with meticulous attention to detail and an uncanny ability to create atmosphere.

Max Fridman: Giardino’s artistic coming of age

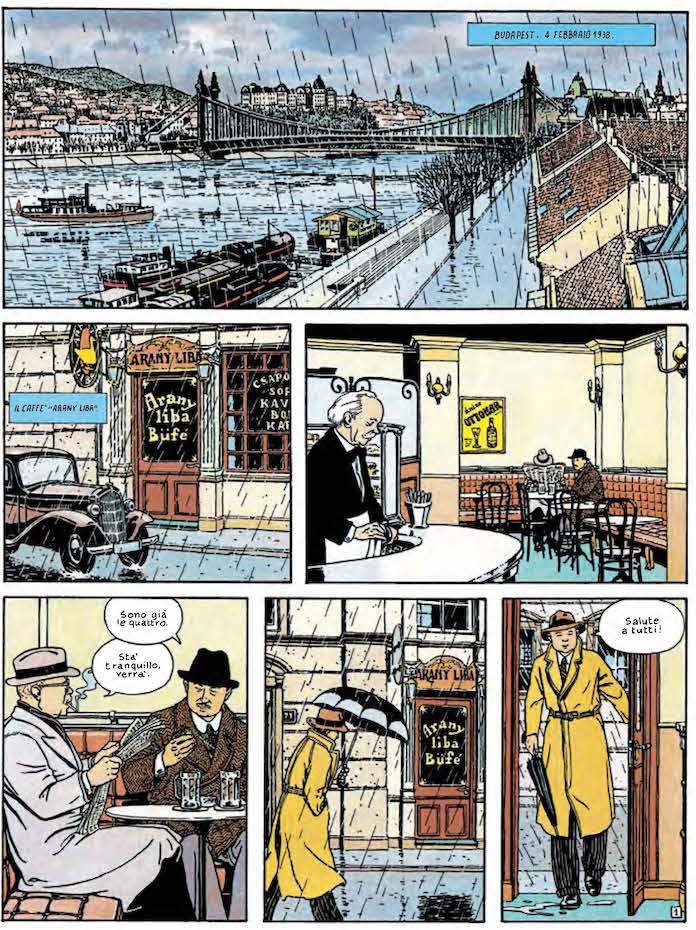

Vittorio Giardino really hit his stride with Hungarian Rhapsody, the first Max Fridman story, which was published in instalments in Orient Express in 1982. The timing was fortuitous, coinciding with a resurgence in so-called ligne claire. This term was first used by Dutch cartoonist Joost Swarte to describe a graphic language defined by clean and precise lines. Originally developed by authors like Hergé, the creator of Tintin, and adopted by the likes of Hermann, Juillard and Pellerin, ligne claire is masterfully employed by Giardino for sinuous and seamless storytelling.

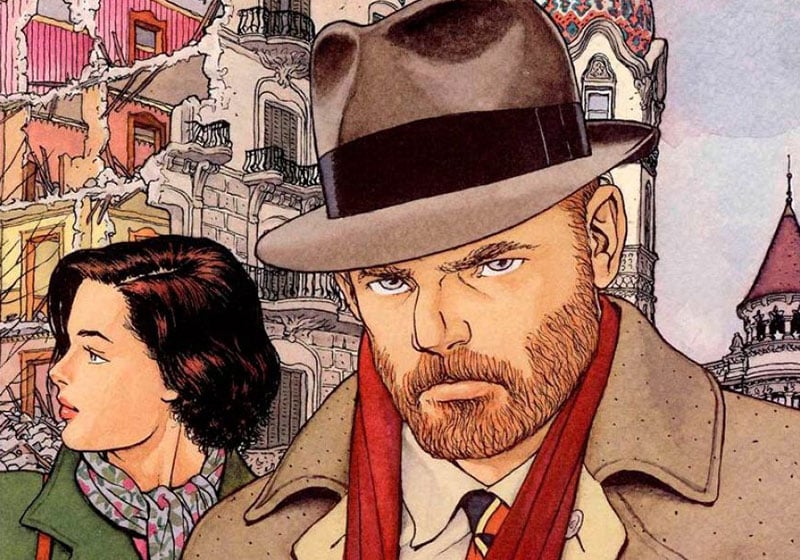

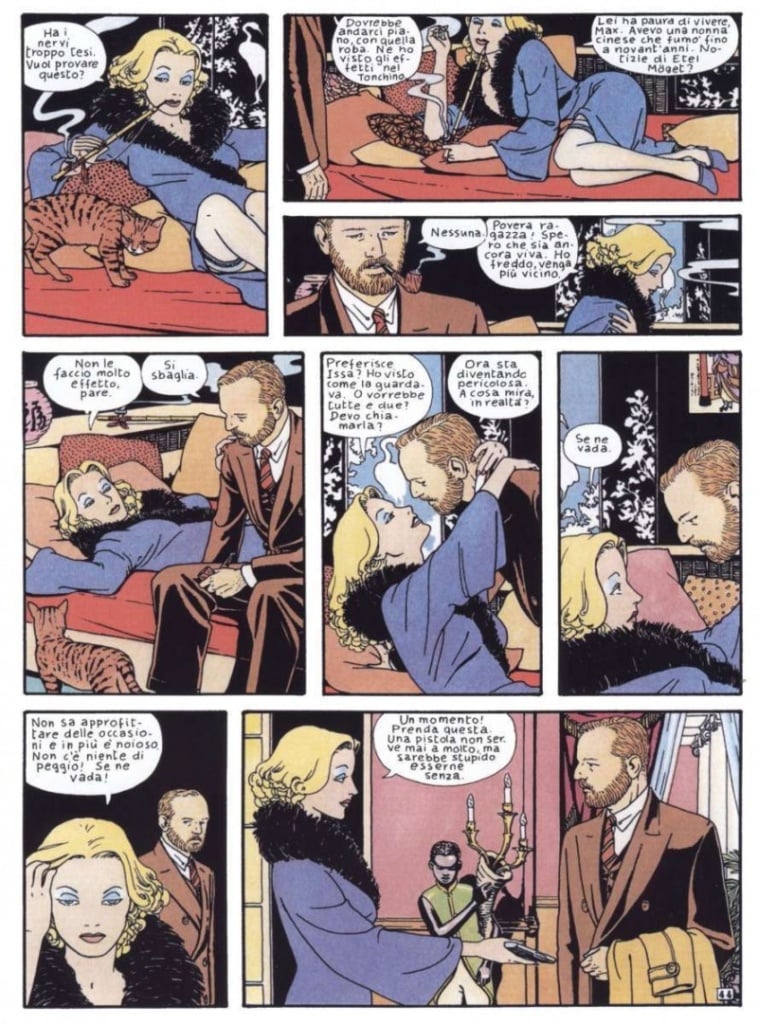

The character Max Fridman is an ex-secret agent and specialist in international disasters who works for the “Firm”. He is blackmailed to come out of retirement and rejoin the great game of espionage in this spy story. As in much of Giardino’s work, there is a strong element of personal introspection, with the main character forced to confront his convictions and his fate as the tide of history sweeps over him.

Political battles and personal fortunes intertwine as Giardino conveys a sense of disillusion, a desire for justice and a quest for an ideal that seems ever further away. Giardino’s ability to mix the personal with the political makes Max Fridman one of his most accomplished pieces of work, a comic that doesn’t just tell a story, but asks the reader to reflect upon important social themes.

Drawings are in the author’s trademark realistic but retro ligne claire. Pages are laid out French style (which means square or rectangular panels, with nothing protruding beyond the grid) and become ever more complex as the series goes on. Giardino adds more details and his approach to light, shade and colour is increasingly sophisticated, as is his panel composition: it’s a masterful piece of visual storytelling.

The Max Fridman character features in La Porta d’Oriente (1986) as well as No Pasarán vol. I (2000), No Pasarán vol. II (2002) and No Pasarán vol. III (2008), which explore Nazism, the Spanish Civil War and Stalinism.

The masterpiece: Jonas Fink

With the success of Max Fridman, Vittorio Giardino made a name for himself in Italy and France as a creator of realistic comics telling gripping stories for adult audiences.

He dabbled in other genres, including erotic comics with Little Ego (a hat tip to Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo) and short stories, some of which featured in Corto Maltese and Il Grifo, such as La terza verità. He also produced stories for national newspapers and magazines like la Repubblica and L’Espresso, as well as illustrations for fashion magazines. But it wasn’t until 1991 that he published his masterpiece: Jonas Fink.

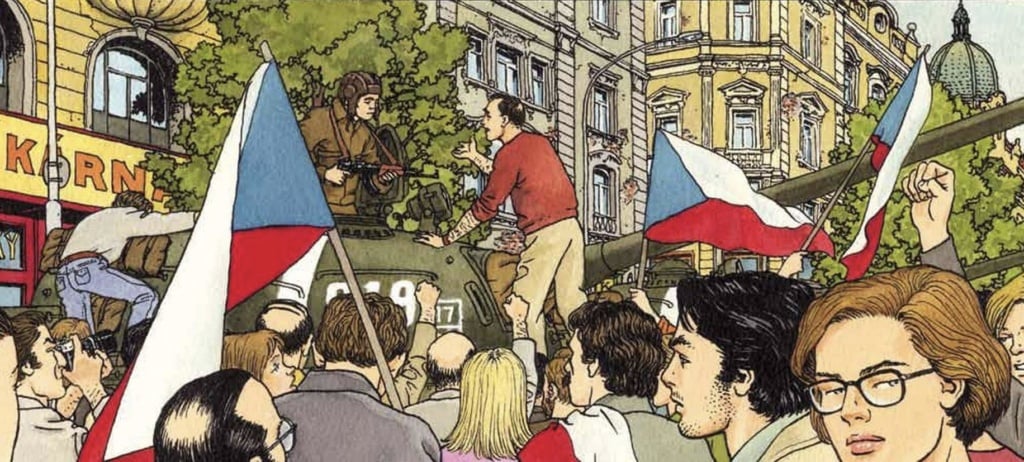

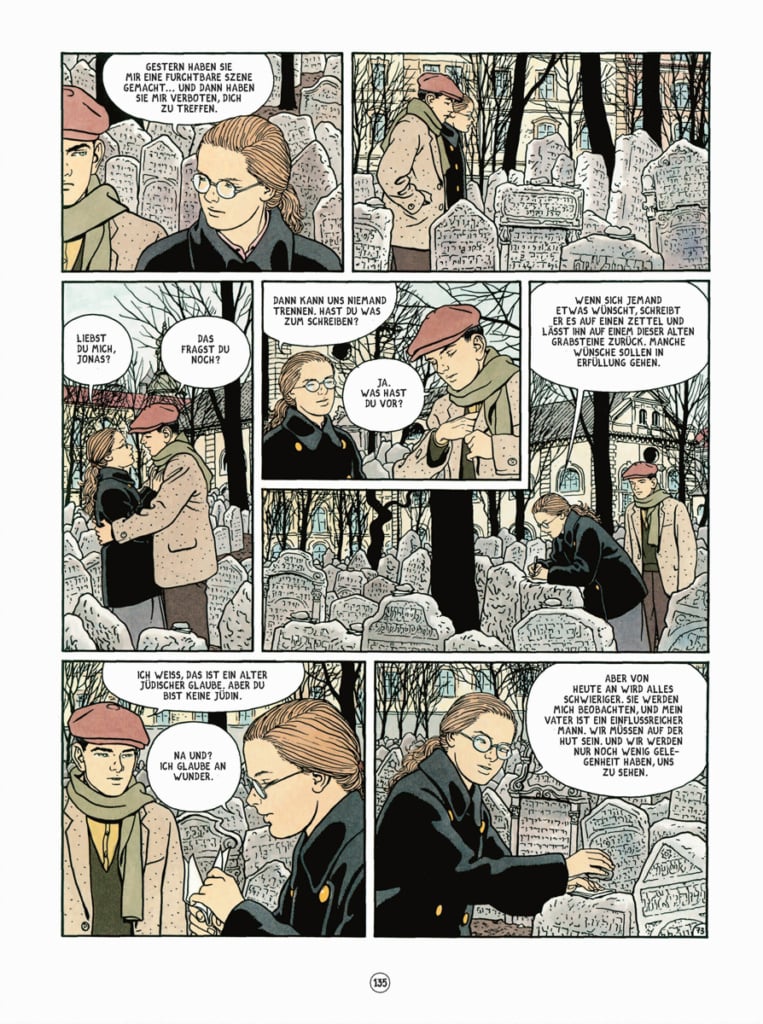

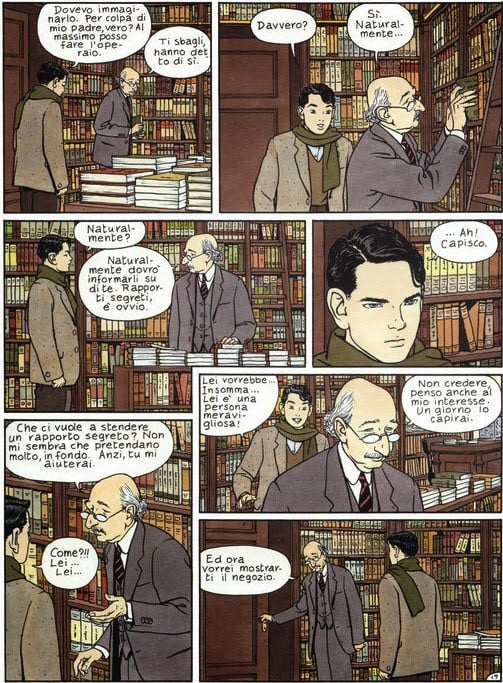

Featuring Giardino’s best-loved character, the Jonas Fink series was published over a 25-year period that began shortly after the Berlin Wall came down. It’s split into three chapters: the first, Childhood, was published episodically by Il Grifo magazine between 1991 and 1994, then as a single volume in 1997. The second chapter, Adolescence, came out in 1998. And finally, after a 20-year hiatus, Giardino released the third and final chapter, The Bookseller of Prague, in 2018.

Set in Prague between 1950 and 1990, it tells the story of a Jonas Fink, a young Jewish boy who sees his father arrested by the communist regime in an anti-bourgeois and antisemitic purge. Here again, Giardino shows how the great events of history shape the lives of ordinary people. He explores the complex themes of the Holocaust and Soviet totalitarianism through intimate storytelling that focuses on the central character.

In Jonas Fink, Giardino’s penwork is at its most evocative and sophisticated. Impeccably put together as ever, the artist’s panels expertly express a full gamut of emotions, from tension and fear to hope and optimism, as Fink’s life is caught up in historical events.

Vittorio Giardino’s legacy

To this day, Vittorio Giardino remains actively involved in comics. His work shows how comics can be a powerful language for talking about historical, social and psychological themes with a depth rarely found in other media. His ability to tell complex stories about multi-faceted characters and universal themes has influenced entire generations of cartoonists and will undoubtedly inspire more.

Giardino’s legacy is not just visual, but cultural, too: his approach to comics has elevated the medium, taking it from pure entertainment to a tool for social and historical exploration and reflection: in his hands, comics are drawn literature.