Table of Contents

The golden age of video game magazines was the 1980s and 1990s, when the internet

was still in its infancy, used only in the workplace and by a handful of early adopters. Back then, specialist information mostly came from printed magazines, creating true communities of fans, who exchanged information at what would now be considered a snail’s pace.

Meanwhile, video games went from being a niche pastime to a mass phenomenon, and the information, reviews and analysis columns in video game magazines played a vital role in this evolution of gaming culture.

From the 2000s onwards, as the web continued its unstoppable ascent, video game mags began to disappear from newsagents, apart from a few exceptions, which managed to cling on. When the genre was at its peak, however, there were vast numbers of them, each one with a different style in terms of both its graphics and tone of voice. Listing them all would be impossible – in many cases there were even magazines dedicated to individual gaming platforms.

Instead, we have selected some of the best video game magazines from the 1980s to the present day, both from Pixartprinting’s home country of Italy and the rest of the world, and ranging from ultra-serious to very light-hearted. Taken together, they perfectly represent the history and countless changes in this constantly evolving medium.

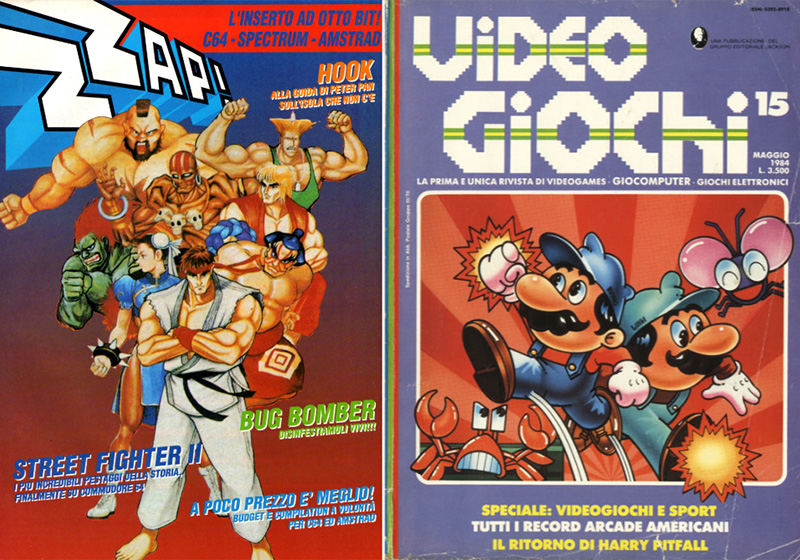

Video Giochi

This was practically the first Italian magazine dedicated exclusively to video games, launched in late 1983 by the Jackson publishing group. Video Giochi was written by Studio Vit, led by Riccardo Albini, who would go on to create other history-making magazines in subsequent years.

It was inspired by the American magazines being produced at the time, and was also the first publication to create a genuine community of (mostly very young) readers, who interacted with the editors by letter. This was a period when shops were selling the Atari 2600 and Colecovision, practically prehistoric in home console terms.

There was a special title for each of the magazine’s various content types: for example, news came in a section entitled “Ready”, the reviews were headed ‘A che gioco giochiamo?‘ (‘What game are we playing?’) and the column on arcade games was entitled ‘Al bar‘ (‘At the bar’). Arcade games have now largely disappeared from our daily lives, as have games rooms, the public spaces where people once shared their passion for video games.

Video Giochi created a spin-off entitled Home Computer, and from issue 29 the two merged, taking on the name Videogiochi & Computer. Production stopped in April 1986, when Studio Vit decided to create and edit a brand-new magazine…

Zzap!

That magazine was Zzap!, first published that very same year, 1986. Predominantly dedicated to systems like the Commodore 64, and to a lesser extent the consoles of that era, the early issues in particular had a very basic graphic design. It was only the advent of the Macintosh in 1987 that finally led to full four-colour printing on all pages.

What set Zzap! apart from all the magazines that came before it was its editorial slant, especially in its reviews. While previously these had simply been descriptions of the characteristics and game modes, here the editors took on a central role, including personal opinions in dedicated boxes that even included a hand-drawn portrait of each reviewer.

With its wacky columns and division of reviews into categories like graphics, sound, desirability and longevity, Zzap! was a seminal magazine for the sector, paving the way for a particular type of specialist journalism. Following several changes of publisher and a decline in the number of releases for 8-bit computers, Zzap! finally closed in 1992.

The Games Machine

1988 was the year of the first issue of The Games Machine, also known as TGM, which is still available in newsagents today, making it the longest-running magazine in the sector published in the West.

Initially masterminded by Bonaventura di Bello and published by Edizioni Hobby, it focused on video games for 16-bit computers, i.e. Amiga, but also included reviews for systems like NES and Sega Master System. In 1991, the magazine transferred to the Milan-based Xenia Edizioni while the publisher was in its heyday.

Xenia completely overhauled the magazine: the number of pages increased from 100 to 180 and the articles became less wacky and much more intelligent and witty. During this period, screenshots of unreleased games could only be depicted on paper, and readers’ letters created a lore of their own, combining stories, characters and slang unique to each magazine. In other words, it was the analogue predecessor of what we would now call a community.

Consolemania

In 1991, The Games Machine‘s sister magazine, Consolemania, came out, dedicated, as the name implies, to console games.

This time the wacky style permeated almost every page. A news section was followed by previews and reviews: the reviews were often very lengthy, with half of the text recounting the editor’s personal affairs, rather than anything related to the game.

Although it gave the impression of having no rules, these were actually specific editorial choices. Consolemania was the ultimate light-hearted magazine, and was often accused of not treating video games seriously enough.

Super Console

Super Console, launched in February 1994 by Futura Publishing, was a magazine unlike any other. It initially only covered Nintendo games and consoles, but in 1995 it expanded its horizons to include other products, like the PlayStation and 3DO consoles. For a few years it even changed its name to Super Console 100% Playstation.

The magazine’s editorial line was what made it stand out, particularly when it was managed by Ivan Fulco: it categorically refused to go down the wacky route taken by its competitors, and instead featured essays on video game culture and even theoretical, almost academic writing on this constantly evolving medium.

One particular issue of Super Console went down in history: it came with a book on the history of video games, the thesis the magazine’s author Matteo Bittanti – now an author and lecturer – had written for his degree.

Super Console ended after its hundredth issue in February 2003.

PSM

In 1998, a new magazine arrived in the world of specialist Italian publishing like a bolt from the blue: PSM. With its garish graphic style, covers illustrated in the style of American comics and a more ‘pop’ layout, for better or worse it introduced a completely different approach to video game journalism. It was also the first publication to design its own mascot: Chibi.

The magazine contained all the classic content that fans expected from this type of product: news, previews, reviews and columns. However, the texts did not get bogged down in personal ruminations or philosophical musings; they went straight to the point in their description of the virtual experience.

After issue 187 in December 2012, PSM started again in 2013 with a ‘new’ number 1. It folded in 2017, before returning to news stands in late 2023 with some of its original editorial staff.

Edge

One of the world’s most popular surviving video game magazines is undoubtedly the UK-based Edge. The first issue came out in 1993, produced by the highly experienced specialist journalist Steve Jarratt.

The magazine is best-known for its iconic covers and its ‘The Making Of’ column, a behind-the-scenes look at how the top video games are developed. Its columns are another trademark feature: spaces where experts from the sector (including the Italian artist Matteo Bittanti) offer a wide range of opinions and more in-depth thoughts about the video gaming world. Edge also launched an Italian edition, but it was halted after 25 issues.

Famitsu

Famitsu is probably the world’s most famous, most important and longest-running video game magazine. It has been published in Japan since 1986, and is practically an institution when it comes to opinions on the latest releases.

Famitsu comes in various editions, and still manages to sell hundreds of thousands of printed copies. On top of its interviews with game designers, editorials and columns, the Famitsu feature that has made the biggest impression is the scoring system it uses for new releases. Every title is tested by four of the publication’s journalists, who give their opinion and a mark from 1 to 10. These are then totted up, making the highest possible score 40, something only very few games have ever achieved.

Micromanía

Second only in renown to Famitsu, and launched not long before the Japanese title, the Spanish Micromanía was one of the longest-running video game mags in the world. The first issue was dated May 1985, making it one of the first publications in Europe dedicated exclusively to console and PC games.

It managed to adapt to the myriad changes and new trends in the video game industry by continuing to expand its coverage to feature all gaming platforms. Over time it also changed its format, layout and publication frequency, and added new sections including strategy guides, analysis, investigative reporting and much more.

Micromanía finally closed in January 2024, after 355 issues and 39 years in business.

Joystick

Joystick, initially known as Joystick Hebdo, was one of France’s most successful video game magazines. It was founded in 1988 by Marc Andersen, and was released as a weekly publication for the first two years. It became monthly in 1990, and was most famous for its cover mount: floppy disks, CD-ROMs and then DVDs that came free with the magazine, and which included some full games.

The magazine had various columns, including reviews and previews, and at certain periods the issues reached almost 300 pages, focused on video games for computers like Amiga, Mac and PC. After changing publishers several times, the magazine finally folded in 2012.

Other magazines

Hundreds of video game magazines have been published in Italy and across the world over the last few decades. From Giochi per il mio computer to Game Power, and from K, Game Republic, Mega Console and GamePro to Nintendo Power, each one epitomised its era, and they all played a crucial role in promoting video games as a form of entertainment and culture.

We will conclude our journey through the world of video game magazines with a thought that, while it may seem trivial, is difficult to argue with: although the web has greatly expanded our access to information, it is still impossible to beat the experience of flicking through a magazine and appreciating a well-designed layout.