Table of Contents

The world’s leading centre for textile images, the textile printing museum in Mulhouse, France, known locally as Musée de l’Impression sur Etoffes, houses more than 6 million patterns. Located in a city that has been synonymous with the textile industry since the 18th century, the museum is the key to understanding Mulhouse. In 2018, its annual temporary exhibition includes an audio walk specially created by composer André Manoukian.

“Bal(l)ade” is a musical meander through the history of textiles – from the 17th century to the present – brought to life by a panoply of digital technology. We take a closer look at a small museum that quietly collaborates with some of the biggest names in contemporary couture and decoration.

Mulhouse: a major centre in the history of textiles

The insatiable demand for imported Indian fabrics in Europe from the 17th century onwards meant that many textile manufacturers set up shop in the Kingdom of France in the 18th century. This delighted everyone, except wool and silk makers, as the new competition meant considerable loss of earnings for these trades. As a result, measures were taken to protect these industries: the import, manufacture and sale of these printed textiles, or indiennes, as they were known, was prohibited.

Despite severe penalties – including exile from the kingdom – it was difficult to completely ban this hugely popular new fabric. At the time, Mulhouse was not part of France and made the most of this situation, getting a head start that put it more than ten years ahead.

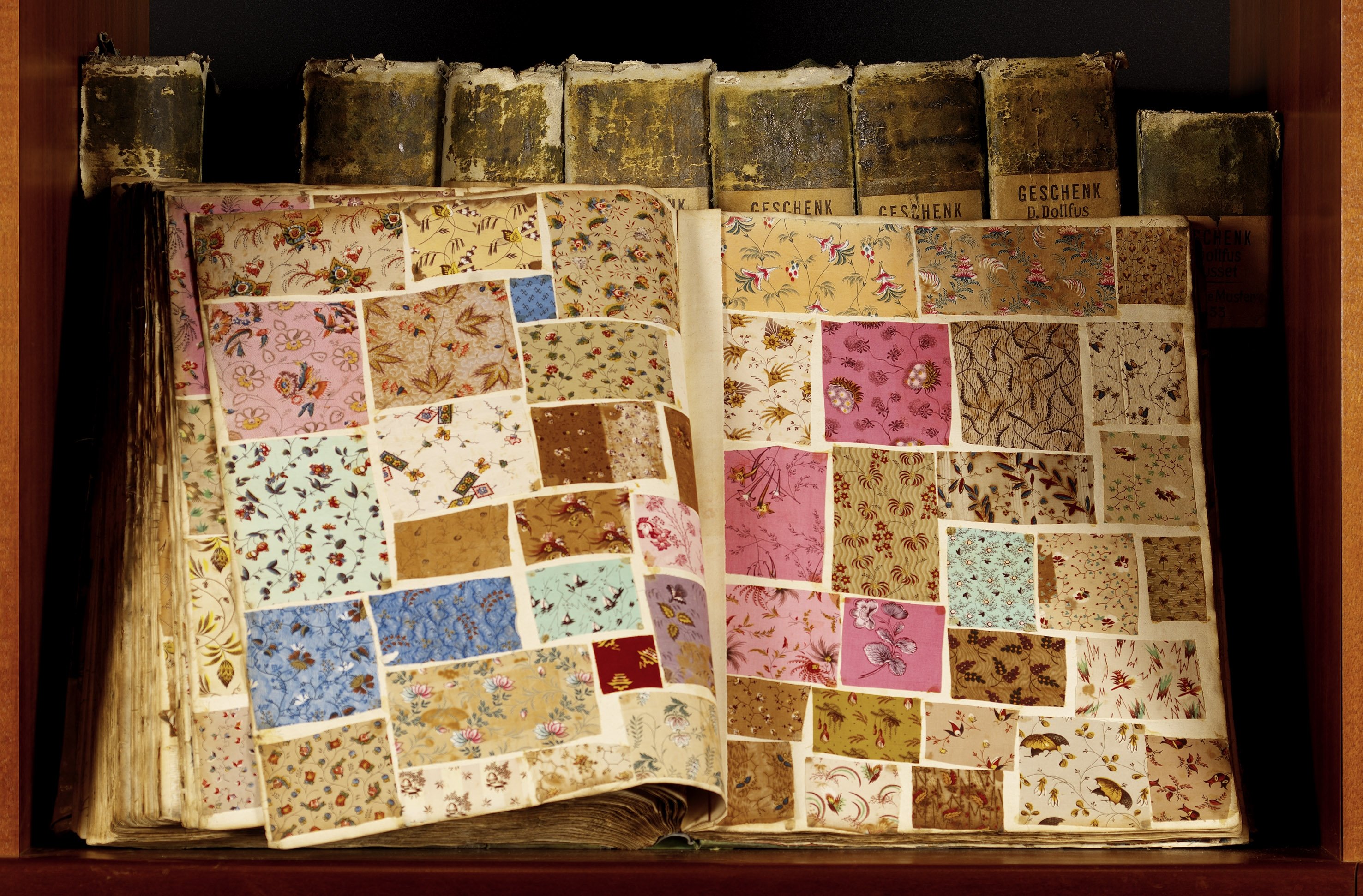

Furthermore, the geography of the city lent itself particularly well to textile manufacturing and trade, with its strategic location on the salt road and abundant water supply. The museum’s origins date to 1833, when Mulhouse’s industrialists decided to get together and start collecting prints. But it wasn’t until 1955 that the museum officially opened its doors. Today, it welcomes over 30,000 visitors a year.

Textile printing since its inception in Europe: 4 key periods

Indiennes

The roots of textile printing lie in India. Since roughly 2000 B.C., Indian artisans have been decorating cotton fabrics known as “indiennes”, French for “Indian”. They use a mixture of two techniques: recurring motifs are obtained using a small piece of wood (think of it as an inking pad), while figurative parts are drawn using a reed pen.

The manufacturing process also uses mordants, metal salts that are applied to the fabric to fix natural dyes. This technique introduced a rich palette of colours, with rose madder and indigo blue chief among them. Indiennes were the first printed fabrics to arrive in Europe, reaching the continent at the end of the 16th century.An instant success, they were highly sought after by Westerners for clothing and interior decoration alike.

In the 17th century, trade between the East and West intensified. The French East India Company began importing tonnes and tonnes of these lightweight fabrics. It also exerted a strong influence on the iconography featured on indiennes, giving direct instructions to Indian artisans to ensure fabric designs catered to European tastes: this meant a predominance of stylised flowers with undulating stems and natural or imaginary plant patterns.

18th century textiles

Demand for indiennes was such that the French East India Company was unable to keep up. In the 1640s, Armenian merchants settled in Marseilles and began replicating the techniques to manufacture indiennes: it was the birth of textile printing in Europe. England and the Netherlands also entered the market. French producers were hugely successful, sparking strong protests from wool and silk makers, which would eventually result in the Kingdom of France banning indiennes.

In 1759, the manufacture of indiennes was legalised and production recommenced in earnest across Europe, led by Switzerland, Great Britain and the Netherlands. The tools used were the same as for traditional printing: a small piece of wood and an inking pad. Although production costs were low, a real advantage, there remained questions over the fragility of the material, which prevented fine engraving.

Brass was subsequently introduced, allowing for finer engraving, before the wooden board was complemented by the engraved copper plate, which was developed in Ireland. But success was limited as the cost of this tool meant it was not cost effective.

19th century textiles

The 19th century revolutionised textile printing. Machines took their place at the heart of the creative process. The advent of copper rollers saw a 25-fold increase in output, which ensured a return on the initial capital outlay. Developments in dye chemistry also brought about significant change in textile printing. In 1856, British chemist Sir William Perkin discovered mauveine, the first synthetic organic dye. His discoveries in the field of colour would spur significant aesthetic research and innovation.

20th century textiles

In the 1930s, a new printing technique emerged: the flatbed. Gauze is stretched over a frame and the areas that are not to be printed are covered in varnish: it works a bit like a stencil. The same thing that occurred in paper printing in the 19th century happened in textile printing in the 1960s: the flatbed was replaced by a cylinder. A rotary screen made from micro-perforated nickel transfers the dyes. This quickly became the dominant technique used in textile printing.

And today?

Digital ink-jet printers have revolutionised textile printing because they do away with the costly and time-consuming process of engraving the screen: all that remains are the graphic design costs. This makes short print runs cost-effective.

The Bal(l)ade temporary exhibition: Q&A with Céline Dumesnil, development manager at Mulhouse’s Musée de l’Impression sur Etoffes.

This year’s temporary exhibition is a deep dive into the museum’s collection, which has been completely overhauled for the occasion. The textiles are brought to life through digital technology like video mapping, sound design and interactive multimedia, while an extra layer of texture is added by the exhibition’s soundtrack, composed by André Manoukian. Céline Dumesnil, development manager at Mulhouse’s Musée de l’Impression sur Etoffes, gives us the low down.

Can you tell us about your temporary exhibitions at the museum?

We work on the principle of annual temporary exhibitions. We always try to work with the same goal in mind: to showcase this rich heritage with the help of a highly contemporary stylist, designer or, in this case, composer. We dedicate a large space to the temporary exhibition, which means the museum is transformed every year. We have already worked with fashion designers Jean-Charles de Castelbajac on the theme of childhood, Christian Lacroix on that of cashmere and Chantal Thomass on women… Some superb collaborations.

Speaking of collaborations, how did this year’s collaboration with André Manoukian come about?

It was a lucky coincidence, or rather a serendipitous encounter. One of our partners is Barrisol, a local firm that is a world leader in stretch ceilings. It turned out that André was restoring an artists’ residence in Chamonix and was working with Barrisol on the project. He had used some patterns from the museum’s image bank for this residence. He then came to Mulhouse and we discussed the idea of a future exhibition: a history of patterns since the 17th century. The idea was agreed upon and André said he would be very happy to set this historical journey into music.

What are the main themes of the exhibition?

There are a dozen or so themes: the Mughal rug, the most precious item in our collection, being both our oldest and rarest piece and dating to the beginning of the 17th century; the imitation fabrics, the first European copies inspired by indiennes; cashmere; the textile craze of France’s Second Empire; and other themes like tradition, design, innovation and so on.

Can you tell us more about the use of digital technology in the exhibition?

Many technologies are used to showcase the museum pieces. Video mapping was used for one installation: traditional patterns and silhouettes are projected onto a white dress that acts as a screen. It’s a very modern version of a mannequin that can be dressed in all sorts of ways.

Quick digression: can you explain the principle behind the SUD, the Service d’Utilisation des Documents [Document Use Service] which is part of the museum?

The SUD is a textile library. It contains over 6 million documents by researchers, designers and companies from all round the world. Providing access to archival documents is a business activity that is a source of revenue for the museum. Documents never physically leave the museum. Rather, we provide the client with a high-definition digital version of the hard copy. It allows our heritage to live on through contemporary collections. Our clients include Ikea and Ladurée, the luxury macaroon maker. They can rework the pattern, or use it as is.

What’s your next big project?

Our next exhibition dedicated to flowers on printed fabric, which opens on 26 October and is supported by the Musée Yves Saint-Laurent Paris, as well as fashion houses Agnès B. and Leonard Paris.