Table of Contents

Adventures along the river, collecting and cataloguing new plant species

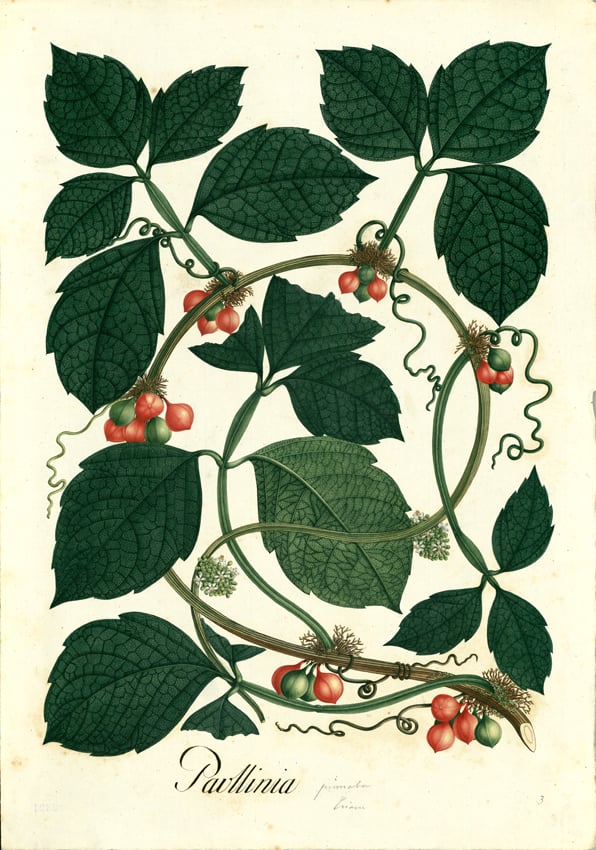

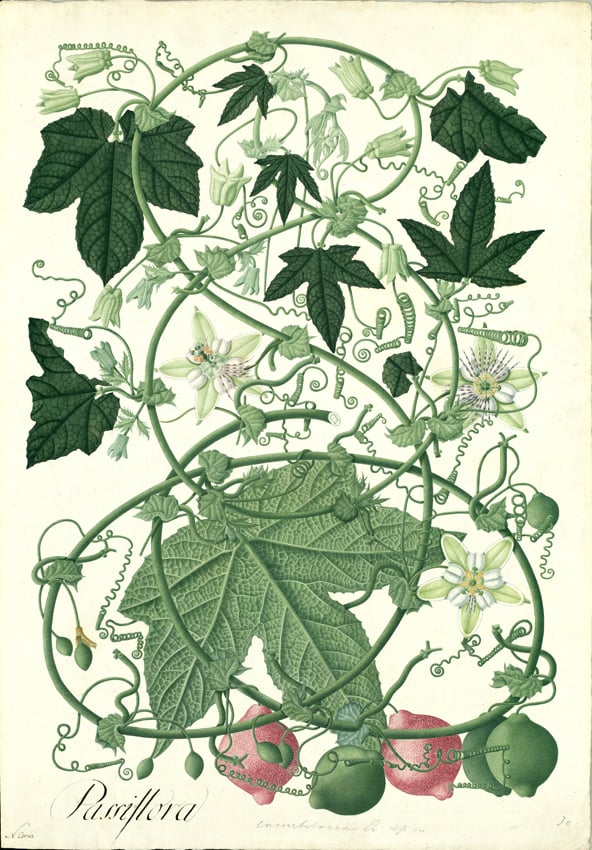

In June 1817, the director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Don Mariano Lagasca, received a shipment at the port of Cádiz of 104 crates that would become one of the greatest contributions in history of the dissemination of scientific knowledge. This cache of treasures, packed with extra special care, was comprised of seeds, resins, minerals, drawings of plants, and the manuscripts of José Celestino Mutis.

The Cádiz-born priest and botanist was the driving force behind the Royal Botanical Expedition to the New Kingdom of Granada, which covered some 8,000 square kilometres along the path of the Magdalena River in Colombia, between 1783 and 1816. The sole objective of this mission was to make an inventory of the country’s natural wealth. Over the course of the voyage, around 20,000 plant species were collected and 6,000 illustrations of exceptional quality were drawn.

In 1954, Spain and Colombia reached an agreement to publish 51 volumes detailing the various plant families studied during the expedition, many of which can now be viewed in digital format.

Between art and science, to help scientists and researchers

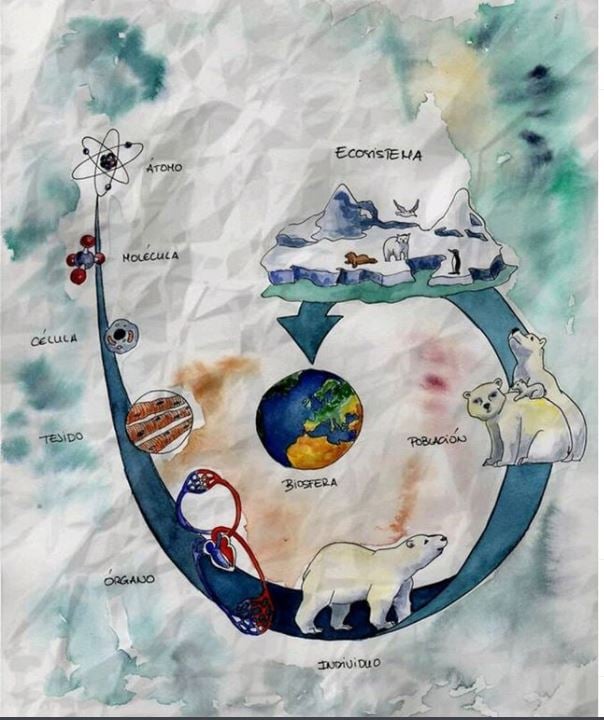

Scientific illustration is a discipline that sits midway between the arts and sciences, which serves to provide visual support for the work of researchers in areas as diverse as botany, biology, zoology, astronomy, geology and archaeology, among others. They may depict an object, a complex process, diagrams, or any other information that requires graphic representation. In any event, this type of illustration requires rigour and precision, and is often the only means by which a scientific concept can be understood.

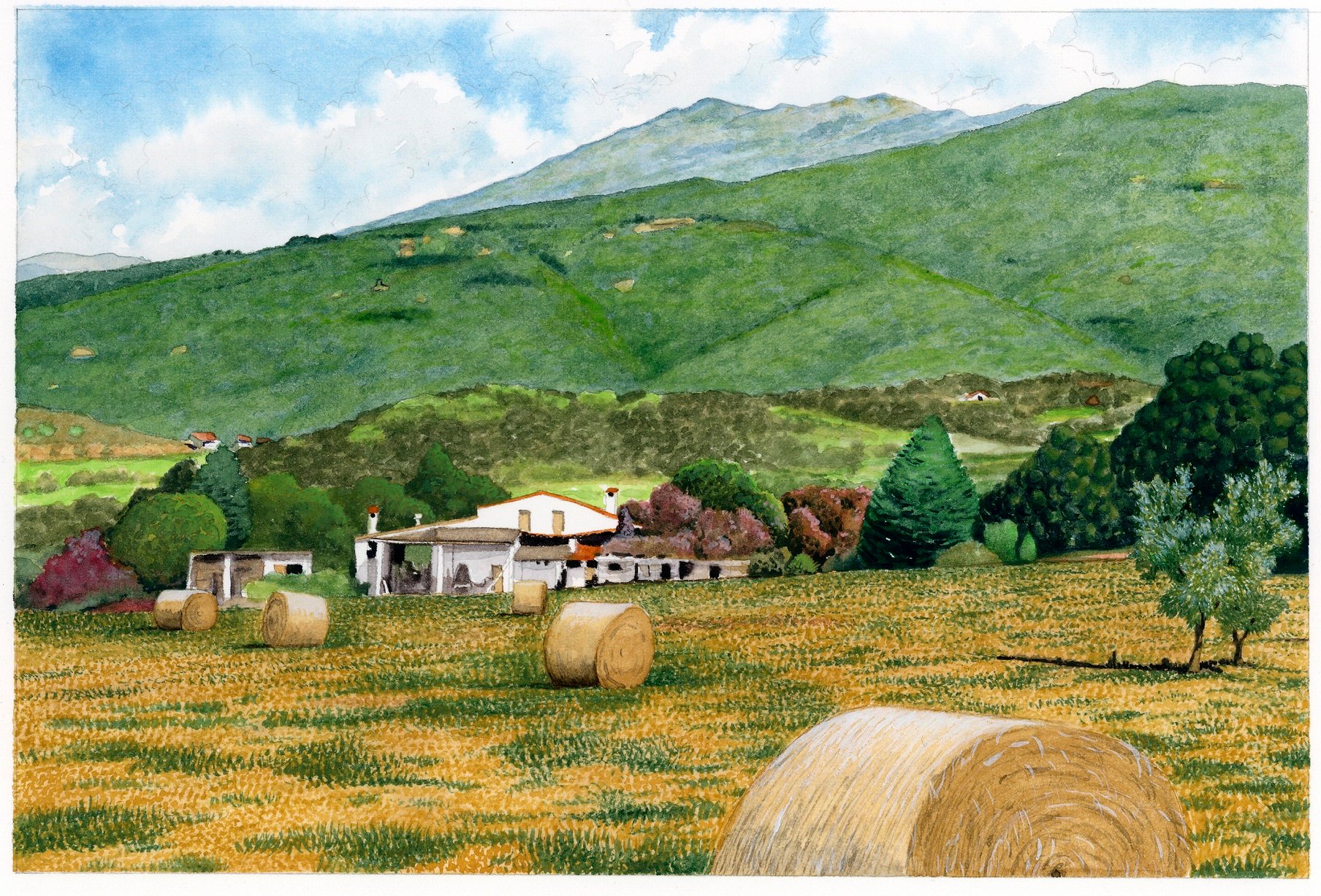

One of Spain’s greatest exponents of this discipline is Carles Puche, a self-taught illustrator who never goes out on the field without a notebook and pencil. He not only illustrates specimens of fauna and flora with great skill, but he also shares his knowledge about the profession in illustration workshops in institutions and universities. In addition, he has taken part in numerous exhibitions, the most international of which was in the New York State Museum; three of his works were selected to be exhibited there throughout 2014.

The job of a scientific illustrator is not only to reliably reproduce a sample. Sometimes they have to create images of situations that do not exist today. How else would we have begun to understand the world of the dinosaurs? In this aspect, Raúl Martín, considered one of the world’s finest paleoartists, has frequently reconstructed the time before humanity, in which these creatures freely roamed, for magazines such as Scientific American and National Geographic. To achieve this, he first had to research many different fields of information, from the environment in which the dinosaurs lived to the type of vegetation. Sometimes, there is no data on these subjects whatsoever.

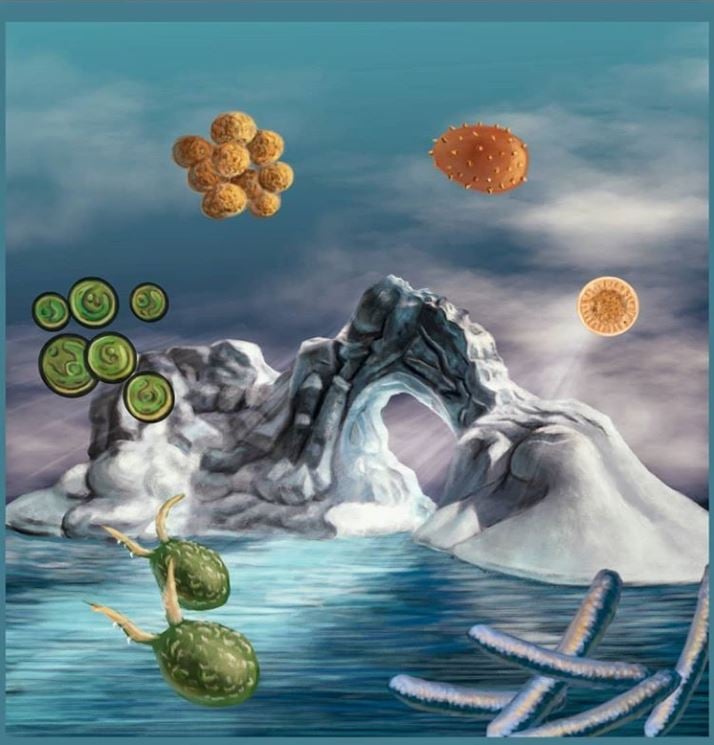

Unlike photography, which represents a specific moment, scientific illustration depicts an entire process. That is why in the field of biology, for example, drawings are essential. María Lamprecht, as well as being a doctor of Microbiology, is also a freelance illustrator who represents complex scientific concepts through images, such as the formation of bacteria communities of the origin of eukaryotic cells, in a very characteristic style.

Scientific illustration is a discipline that not only conveys information to the general public, but is also useful for scientists themselves. Vanessa González Ortiz mostly receives commissions from professors and researchers to design thesis covers, PowerPoint presentations for conferences, scientific posters, illustrations for books, etc. A graduate in Marine Sciences, she decided to become a scientific illustrator while she was a PhD student writing a thesis on seagrass, as she realised that science requires a lot of visual support. Nowadays, González also teaches courses and gives lectures at universities on how to improve scientific research through graphic design.

Scientific illustrators: how to become one?

Formal training in this discipline, however, is still scarce in Europe. In the US there is a greater tradition, with centres such as the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine, at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, which has been training medical illustrators for more than 100 years. The curriculum covers illustration, medical photography, 3D modelling, human anatomy, and much more.

In Spain, specific training in scientific illustration can be found at the Olot Foundation for Higher Studies (Girona), with their Postgraduate Degree in Scientific Illustration of Natural Sciences. The University of the Basque Country also teaches a Postgraduate Degree in Scientific Illustration. Media such as Principia , both an online platform and print magazine featuring illustrated science and literature, helps to spread the word. There is also a competition, Illustrate Science, which has set out to publicise and reward the best in science and nature illustration since 2009.

As for the future, while it’s true that digital techniques are contributing to better illustrations and greater awareness of the work of these professionals, few are able to devote themselves exclusively to scientific illustration. This is due to the fact that, inexplicably, fewer and fewer funds are allocated to these types of projects, which have been taking an artistic approach to science for centuries.