Table of Contents

Today we would like to take you on the first stage of a journey into the world of Italian illustration.

This extremely varied and highly creative sector is brimming with opportunities, and has grown and developed rapidly in recent decades, with passion at its heart.

Over the last twenty years, little by little, trends in the world of visual communication have changed enormously (although the general public may not have noticed at all). New creative professions have emerged, while other roles that already existed, including illustrators, have grown in stature and complexity.

Modern images increasingly seek to create parallel worlds: we have moved from the didactic realism of a certain type of photography to hyper-realism, often exaggerated and caricatured, which blurs the line between reality and fiction (a line that is acknowledged and still just about recognisable in live-action films and special effects, but no longer identifiable in ‘deep fakes’). The concept of photo editing is now universally accepted, to the extent that ‘to Photoshop’ is widely used as a verb, while realistic-looking fantasy creatures and landscapes can be created thanks to 3D modelling. An opposing trend has also developed, embracing surreal, imaginative, conceptual and symbolic ideas, and giving rise to an alternative approach to photography, where disorienting effects are created, with or without Photoshop. As part of this search for alternative realities, illustration has also gained in popularity – concept art has been given a new lease of life in the world of fantasy and comics, and artists are increasingly experimenting with graphic design, creating new images, forms and colours and producing increasingly complex alternative visions that are lapped up by an appreciative public.

The widespread use of digital technologies, even for those who employ analogue artistic techniques, means all these images – both photos and illustrations – can increasingly be tailored to the design concept of the medium where they will be used, effectively turning photographers and illustrators into graphic designers.

These trends have seen illustration take root as a versatile, colourful and innovative communication tool, slowly spreading into more mainstream, kitsch and poorly designed communications too.

IL – Intelligence in Lifestyle, a men’s supplement from the newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore, may have kickstarted this process. Several years ago, in around 2010, it produced trailblazing output that led to international awards and recognition for its deus ex machina, the art director Francesco Franchi (who after many years at Il Sole 24 Ore is now in charge of the graphic layout of La Repubblica and many of the works published by the Gedi group). The magazine used a mix of different languages, with constant crossover between graphic design, illustration and photos, creating a trendsetting infographic language where everything fitted perfectly into the magazine’s overall design and concept. It became clear that images that can be quickly altered, like illustrations, have an advantage over photographs, and this even led photographers to work in a more ‘graphical’ way, both when shooting and in post-production.

During the same period, Wired proposed a new way of using illustration, mixing it, as Franchi had done, with graphic design and data visualisation. These publications and the daily national newspapers revitalised the sector, creating a sort of laboratory for young illustrators that saw new trends emerging, some of which had not been seen anywhere else in the world.

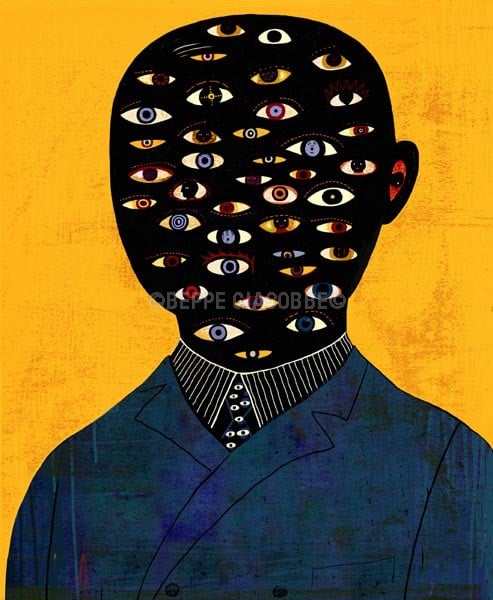

Italian illustration enjoyed a sort of renaissance in this new environment: illustrators already renowned internationally, such as Emiliano Ponzi, Alessandro Gottardo (aka SHOUT), Beppe Giacobbe, Guido Scarabottolo, Valeria Petrone and Olimpia Zagnoli (my apologies to any I have forgotten!) were joined by dozens of new faces. Magazines and newspapers all over the world, where the illustration was previously the sole domain of American and British professionals, received a dose of Italian creativity, as well as featuring top illustrators from Japan, Spain, France and Germany.

What inspired the renaissance in Italian illustration?

In the now distant 2013 (apologies for citing myself, but it serves a useful purpose here) I wrote a short book entitled ‘Illustrazione, l’immaginario per professione’ (‘Illustration, using the imagination for a living’), in which I predicted the arrival of a new type of “hybrid illustrator” who “will no longer be afraid to tackle the market, to create direct relationships with clients, to talk to their audience, to handle technology, to design their own products and manage their career”, adding “because the function of illustration is to reach as many people as possible, using any means available”.

A lot has changed in the world of communication in recent years, most strikingly in the role of technology, both the use of digital tools to create images and the spread of these images online or on various devices. One shift resulting from this new context is the major role played by animated illustration, which is better at grabbing readers’ attention.

A new aesthetic and innovative approaches to an ancient profession have emerged, changing the relationship between image and context, with the illustrator becoming increasingly capable of creating work with graphic design in mind.

What was a complex profession, reserved solely to those with certain technical, art and design skills as well as the ability to depict metaphors or create particularly beautiful and interesting images, has become increasingly open to newcomers, thanks to the exponential growth in the number of courses and schools available and the fact that new technologies – particularly digital drawing and painting – have made it easier to achieve certain results.

Being an illustrator has become ‘trendy’, a profession people aspire to, seen as much more creative than graphic design, especially since it promises the chance to develop an individual style, something the world of graphic design – focused on projects and the concept of the invisible designer – has never been particularly fond of.

This new wave of illustrators went down well with the public, and people started to commission works, expanding the opportunities for illustration to be used.

Now, in this new decade, there are many internationally renowned illustrators in their thirties and forties with a versatile approach to work, able to adapt to the numerous possibilities provided by modern visual communication.

Schools, shows and events for illustrators: helping the profession develop

Over the last twenty years, a significant number of schools have been founded that ‘churn out’ illustrators capable of producing increasingly high-quality work (although for years the most fashionable styles were repeated ad nauseam, creating increasingly soulless clones rather than prioritising variety and creativity). Here’s a list – in no particular order – of these schools, for anyone considering studying illustration in Italy: the IED, in its various forms, was ahead of the curve when it opened in Italy; the ISIA, and particularly its Urbino campus, has excellent tutors and produces top illustrators; MiMaster in Milan, meanwhile, is growing in renown, and allows students to come into contact with big names in international illustration. Various academies have also invested in the profession, and the numerous comics and graphic design schools dotted around Italy, who do a lot of local work, have also shown a certain amount of interest in illustration. One shouldn’t forget the immense amount of work in the field of children’s illustration, which in Italy, thanks in part to the Bologna Children’s Book Fair, the most important trade show of its kind in the world, has created a rush of top-quality ideas and artists, including the Sàrmede workshop, the illustration school in Macerata, Officina B5 in Rome and countless local workshops (it would be virtually impossible to list them all!), often set up by associations who have promoted illustration for years.

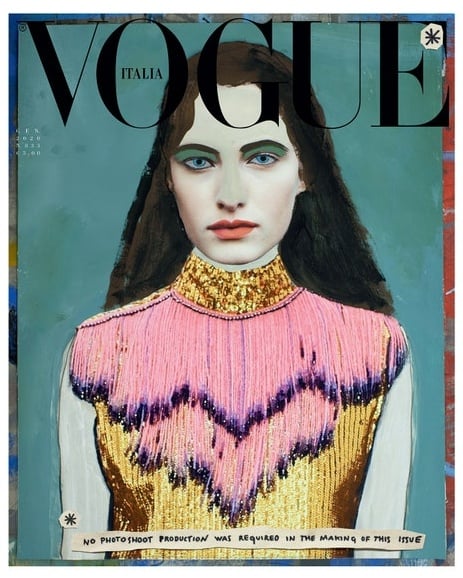

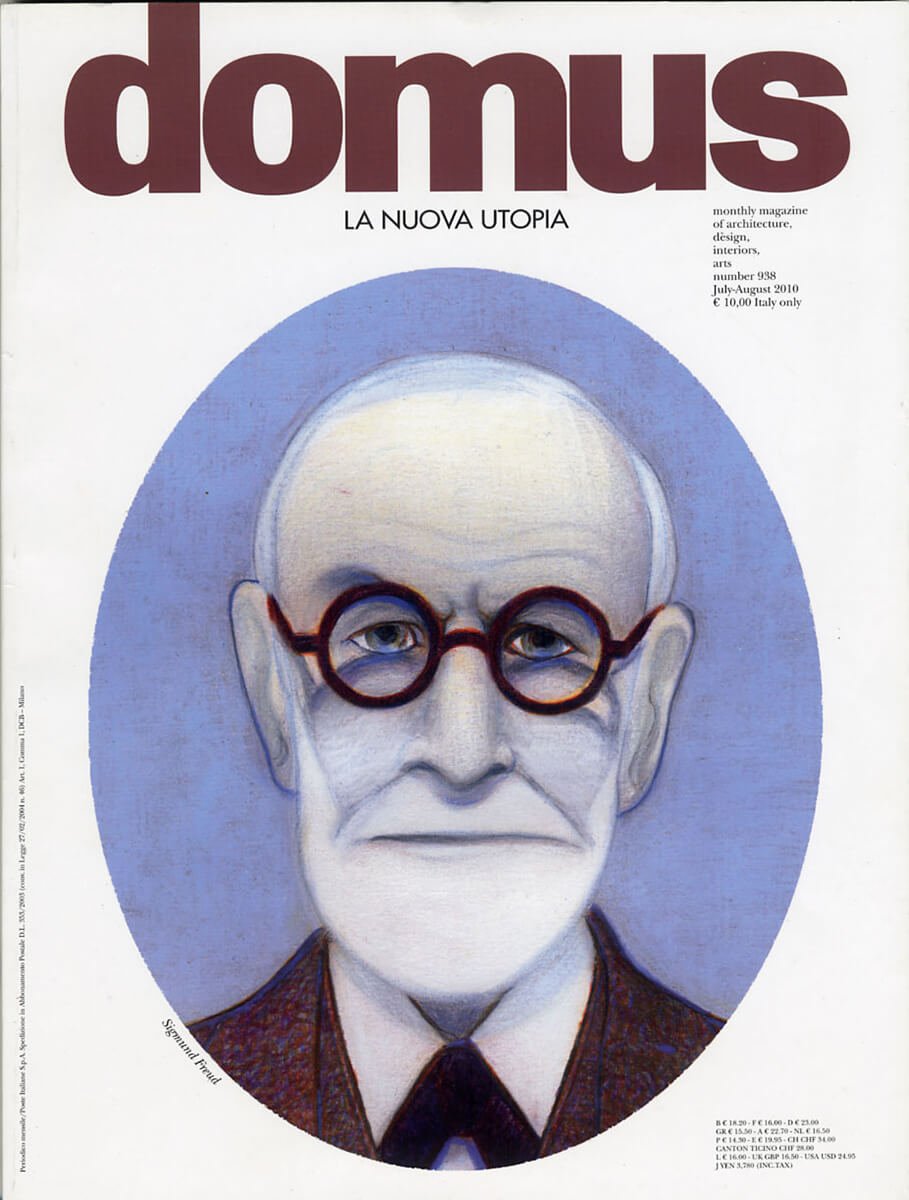

Further proof of the wide interest in this type of image can be seen in the print media, where newspapers and magazines have made growing, and better, use of illustration; consider, for example, the special edition of Vogue Italia, which used drawings and illustrations instead of photos, or the series of Domus covers created by Lorenzo Mattotti. The same trend can be seen in publishing, where, as well as using illustrations on covers, the number of illustrated books (no longer solely aimed at children, but increasingly aimed at adults too) and books that include drawings has gone up.

More traditional, mainstream communication also uses images created by illustrators every now and again, albeit irregularly and nowhere near as frequently as was seen until the 1980s. One almost revolutionary example was the posters created for the 2013 and 2014 Sanremo Music Festival, hosted by Italian TV presenter Fabio Fazio, and entrusted to two artists who are known and loved all over the world, Emiliano Ponzi and Lorenzo Mattotti.

Shows and festivals dedicated to illustration have also sprung up all over Italy, including Tapirulan in Cremona, Illustri in Vicenza, Ratatà in Macerata, Inchiostro in Alessandria, Gomma and Paw Che Go in Milan and UAU in Bergamo, to name but a few; it has also been mixed with the world of comics, in particular at Bilbolbul in Bologna, and been given more prominence at other events and in street art, as seen at Subsidenza in Ravenna, Viavai in Salento, Memorie Urbane in Campania, Outdoor in Rome and ALT!rove in Catanzaro, plus many other, less prominent events.

Finally, Italian illustration and the various trends connected to it have increasingly been promoted online, especially through magazines like Frizzifrizzi, Picame and Osso. There is even now a magazine (available in both digital and printed formats) dedicated solely to the sector: ILIT, or Illustratore Italiano (Italian Illustrator).

This boom in colourful and evocative images also has its downsides: it sometimes gets repetitive, there is a tendency to copy the styles and solutions used by more established artists, the trend for ‘flat’ graphics has now become boring and obvious, and there can be a shortage of inventiveness and experimentation. For the most cutting-edge designs, people to continue to look to American illustration, where the variety of solutions, styles, formats and subjects is much vaster than that produced in Italy. This is in part thanks to a plethora of curious clients and art directors who are good at spotting talent and are willing to invest much more in this kind of applied art, making the country a sort of mecca for illustrators all over the world.

Illustration in Italy today: a vibrant world we’ll describe in several articles

Italy has undoubtedly rediscovered its interest in illustration, and therefore in a metaphorical, evocative, symbolic, often surreal and unusual approach to images, frequently seen as the antithesis of overly didactic and tired photography. The younger generations, and especially Millenials and Generation Z, i.e. everyone born from the 1980s onwards, are au fait with the fantasy language of illustration, the limitless use of images to decorate all objects, and a pop culture featuring manga, anime, video games, lettering, Art Attack rip-offs, artificial colours and new materials (gel, slime and memory foam). In other words, a completely different post-modern worldview that mixes high and low culture, childhood and academic study, speed and emotions.

Our series of articles will take you on a journey through the varied world of illustration. We will attempt to understand it and recognise it, analyse how it can be used, provide information on how to commission illustrations and explain where to find the most suitable illustrators for your projects.

This voyage of discovery will explore a colourful and dreamlike world full of imagination and intellect, which – as it becomes more widely used and promoted – could even change the way we see the world. Instilling communication materials with an inventive vision can help to educate people about art and creative thinking, teaching the general public that using your imagination is not a pointless exercise, but one of the main drivers of any technological or social innovation.