Table of Contents

The Council of Europe was founded in 1949 following the Treaty of London, with the aim of preventing a repeat of the events of World War II. To this day, the 47 members of this international organisation work together to promote democracy, human rights and European cultural identity and seek solutions to social issues.

The Council of Europe should not be confused with the European Union (a political and economic organisation with 27 member states) or with Europe (a geographical region of the world, commonly considered a continent).

Between the year it was founded and 1955, over 150 suggestions of designs for flags to represent Europe were sent unsolicited to the council. There was never an official tendering process – the various proposals came from people all over the world (although France and Germany dominated) after hearing the issue discussed on the radio or reading about it in the newspapers.

Various evaluation committees analysed the proposals, and the design we know today was eventually approved and finalised in 1955. Jonas von Lenthe describes this process and reveals a large number of the ideas that didn’t make the cut in his book Rejected: Designs for the European Flag, which was published in November 2020.

Jonas is a photographer and researcher based in Berlin, who works on art exhibitions and publishes books on extremely niche yet fascinating topics. He became interested in the European flag back in 2016, when the symbol began to spread in cultural and fashion contexts. He started to research the origin of the flag’s design and found out about the hundreds of rejected designs, and so contacted the Council of Europe’s archive, which shared the material with him.

Jonas was struck by the variety and quality of the proposals, which he saw as containing hope for a better future. Although all the designs share the idea of a united Europe as a model for the future, graphically they are extremely varied.

After an introduction, the book is divided into sections: more abstract and simple designs made up of block colours, suggestions based on the letter ‘E’, ‘EU’ or the word ‘Europe’ or ‘Europa’, designs including the sun in various forms, the Swiss cross as a sign of peace and multiculturalism, and then a final chapter on stars, before arriving at the proposal that was eventually chosen. Let’s have a look at some examples from each section.

Block colours

Letter ‘E, ‘EU’, ‘Europe’ or ‘Europa’

The sun

Swiss cross

Stars

Images from Rejected: Designs for the European Flag, copyright Council of Europe

The final section contains various proposals that include a circle of yellow stars on a dark blue background. Officially, the chosen flag was credited to Arsène Heitz, a former postal employee at the Council, but various people can lay some claim to the design. As Jonas says in the book, it is actually very difficult to work out who really created the winning design, and perhaps it is better to think of it as a group effort.

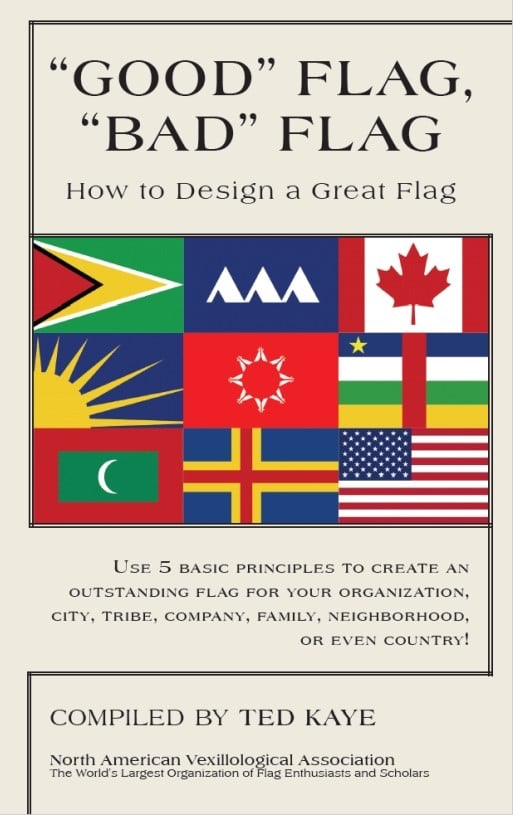

Rejected: Designs for the European Flag uses images to tell the interesting story of a very rare event: the ‘branding’ of a continent – Europe – in the modern age. In 2006 Ted Kaye, secretary of the North American Vexillological Association (vexillology is the scientific and academic study of flags) published the book Good Flag, Bad Flag. Based on five rules, the volume urges designers to opt for simplicity and basic symbolism in their choice of images, colours and patterns.

Unfortunately, in the 1950s Kaye’s book had not been written, and research into flags was not at the level it is today. Despite the unsolicited nature of the suggestions (many of them were sent by amateur graphic artists and illustrators) the European flag’s design makes it unique and recognisable, and reflects the values that have unfortunately been put to the test in recent years by nationalism, the financial crisis and the migrant crisis. Perhaps now is the right time to develop a new design that reaffirms Europe’s ideals?