Table of Contents

Since ancient times, humankind has been seeking and refining techniques that allow shapes and signs to be reproduced quickly and automatically without having to draw or write each one individually. Over 35,000 years ago, humans were using their hands as stencils over which they blew pigment to decorate their caves. This was not just a simple drawing, but an automatic process that enabled (albeit rudimentary) rapid and “mass” production.

Today, industrial printing seems a world away from a manual and instinctive action; rather, it’s a mechanised process that uses cutting-edge technologies. That said, with the exception of digital printing (only possible thanks to computers), almost every other printing technique used today has in fact evolved out of manual processes invented centuries ago.

Below we describe the main techniques for reproducing signs and symbols that humans have devised over the centuries. Some are now no longer used for large-scale production, but continue to be appreciated in the artistic world for their distinctive features. Other techniques, however, have been progressively perfected and mechanised for use on an industrial scale, yet are still based on the same fundamental principal.

Xylography

From the Greek ξύλον, xìlov, “wood” and γράφειν, gràphein, “to write”

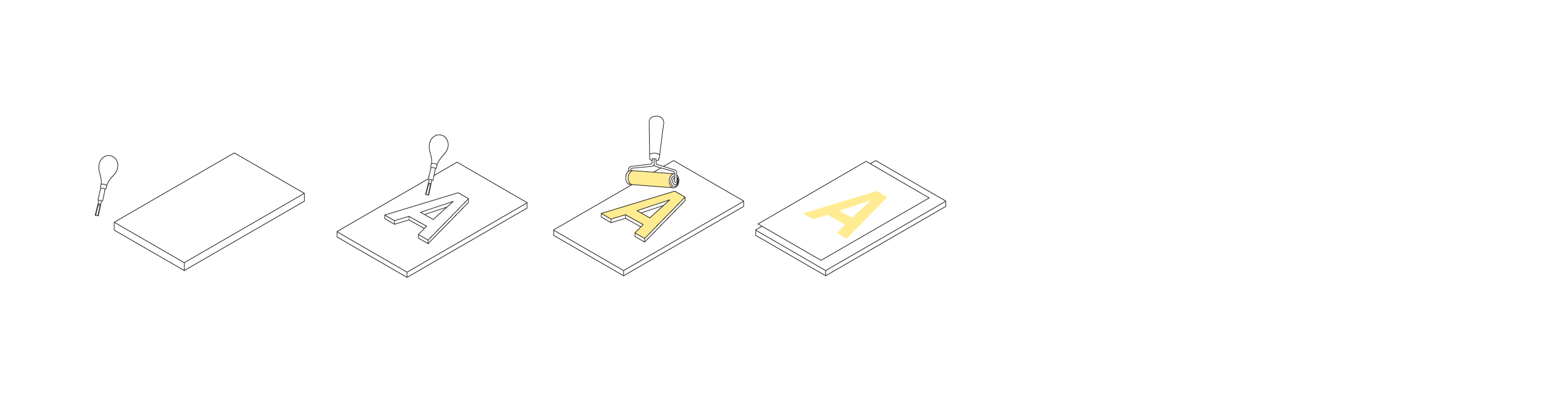

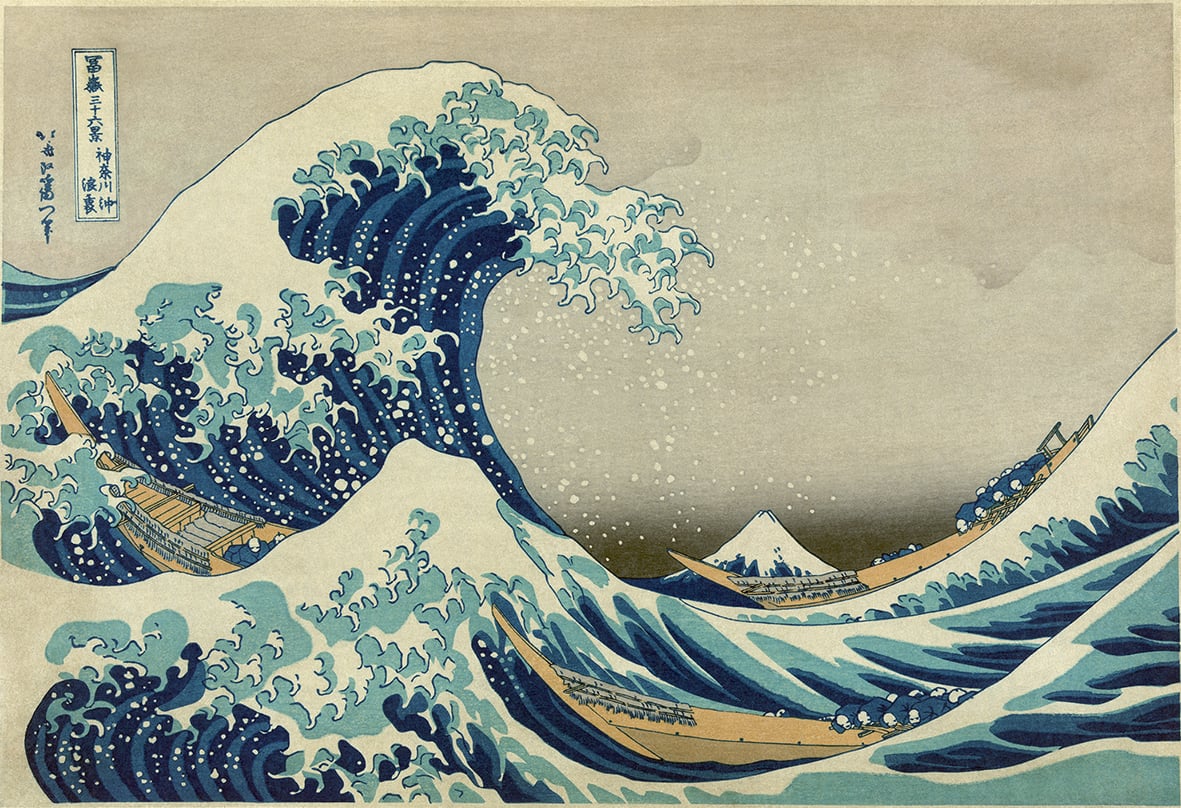

Xylography, also known as woodcut, is the oldest known printing method. The technique consists of engraving a wooden block in relief by using a gouge to remove non-printing parts. The parts in relief are then inked so that, when pressed against a substrate (paper or fabric), they transfer a mirror image to that engraved on the block.

Xylography was even used for printing entire books, using blocks carrying both the text and illustration, until the introduction of movable type printing by Johannes Gutenberg in the second half of the 15th century.

However, the technique continued to be used by artists. More recently, linoleum and Adigraf, which are softer and easier to engrave, have often replaced wood as a substrate, although, strictly speaking, this variant of the technique is called linocut.

Chalcography

From the Greek χαλκός, khalkòs, “copper” and γράφειν, gràphein, “to write”

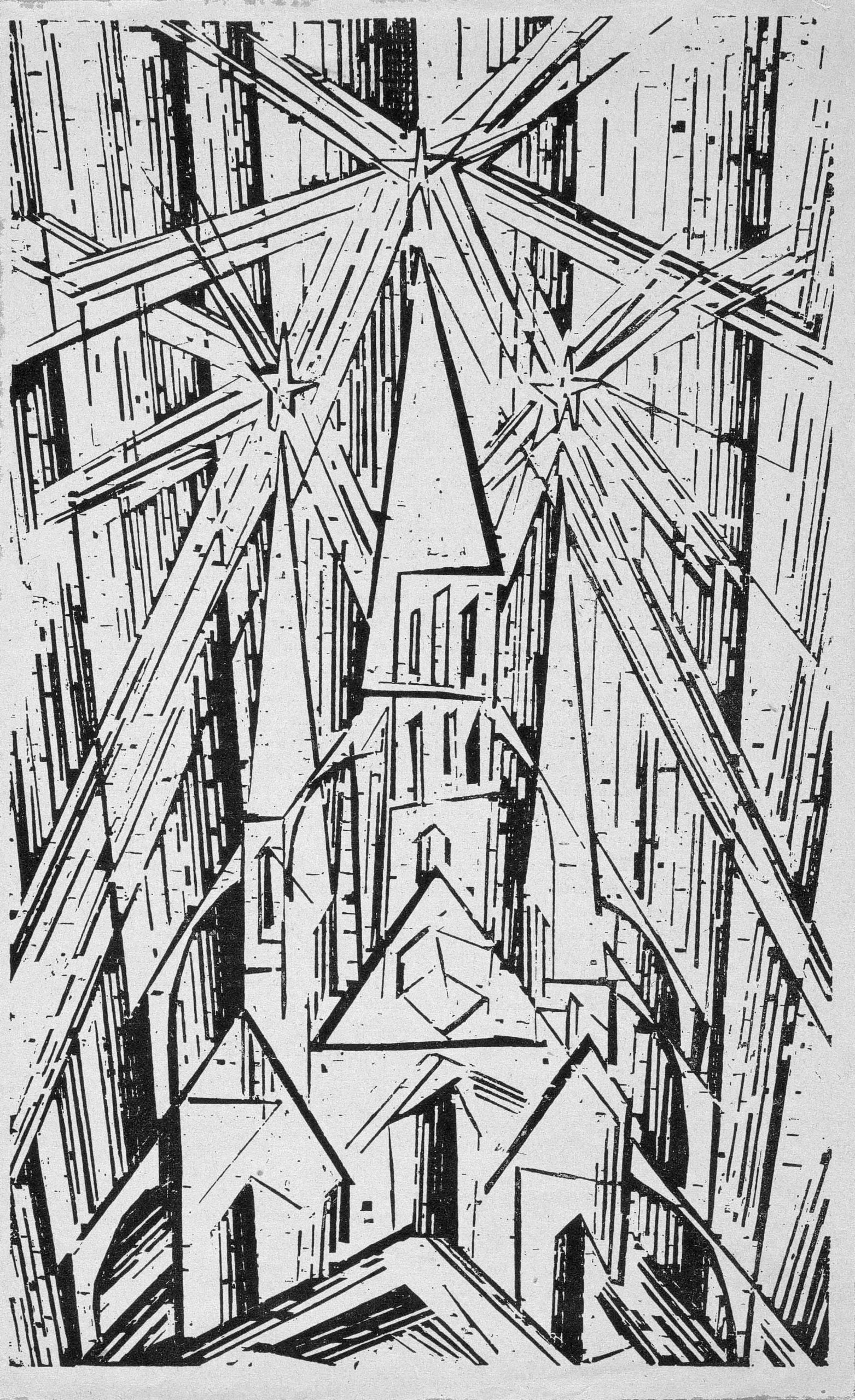

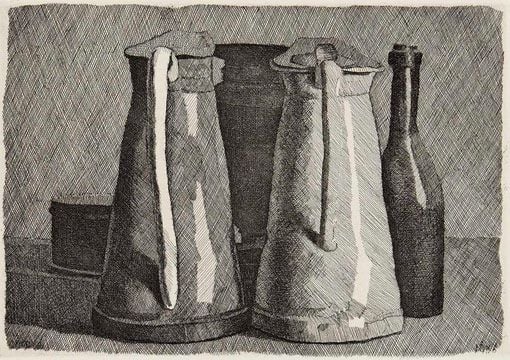

Chalcography is an engraving technique used to create illustrations. Unlike xylography, images are created in positive rather than negative and engraved directly onto the printing plate.

The technique involves engraving a metal plate and then inking the incisions, in other words, the grooves. By applying pressure using a press, the ink that was deposited in the grooves is transferred to the substrate.

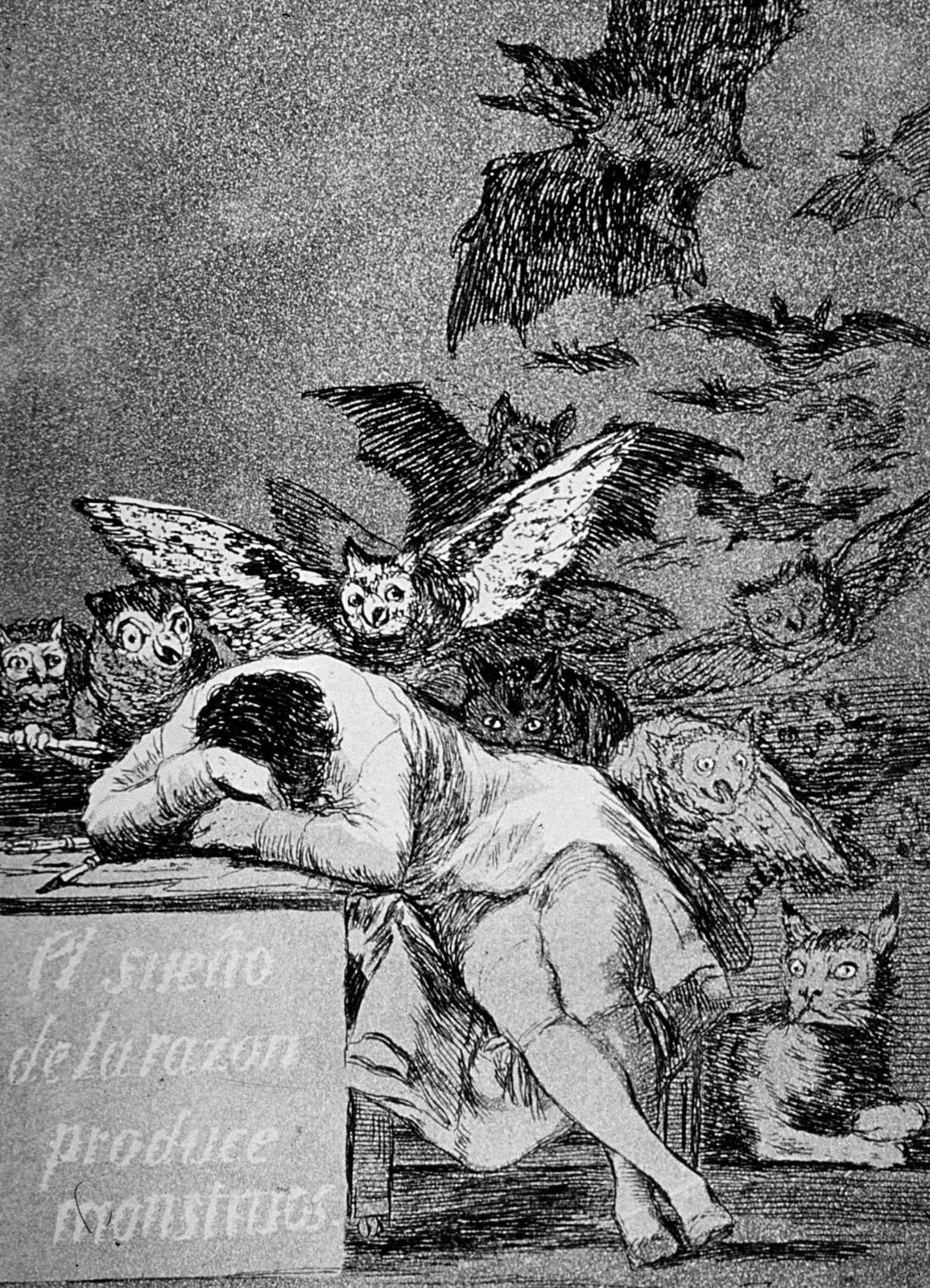

The direct method involves engraving the plate by hand, while the indirect method, known as etching, uses corrosive chemicals to incise the image onto a metal plate. In the latter technique, the plate is covered with an acid-resistant substance; a needle is then used to create the image to be printed by removing this covering. The plate is then dipped in acid, which incises the uncovered parts. The depth of the incision depends on the length of time the plate is immersed in acid.

Rotogravure is a more advanced form of chalcography that uses a rotary printing press with cylinders that have been photomechanically engraved. The ink is transferred to paper using a system of cells of varying depth. The deeper the cells, the more ink they can hold and the darker the resulting print.

Thanks to its glossy, high-fidelity image reproduction, from the first half of the 20th century it was used to print mass-circulation magazines.

Lithography

From the Greek λίθος, lìthos, “stone” and γράφειν, gràphein, “to write”

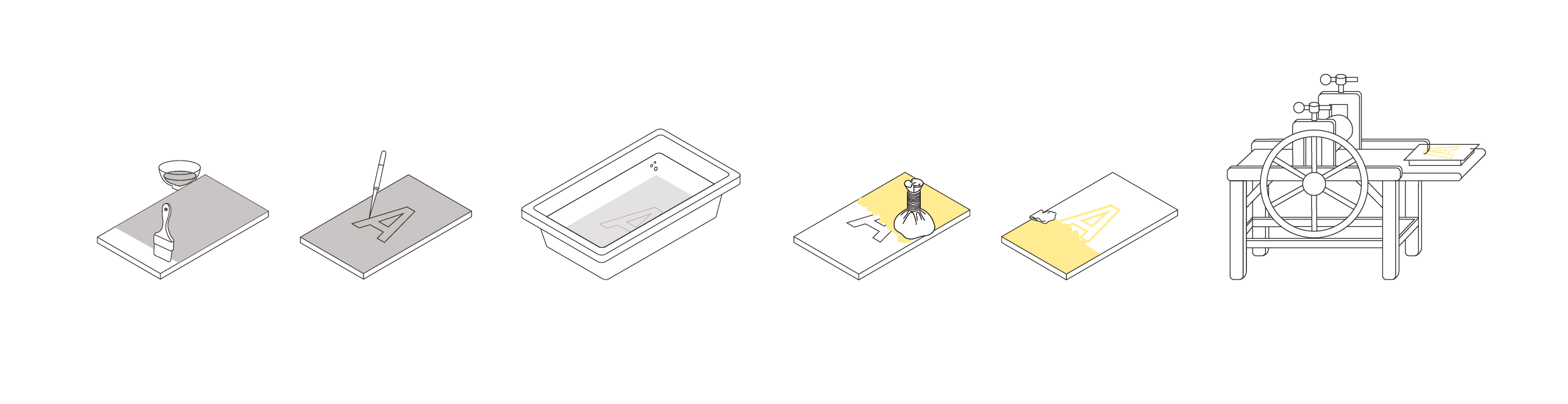

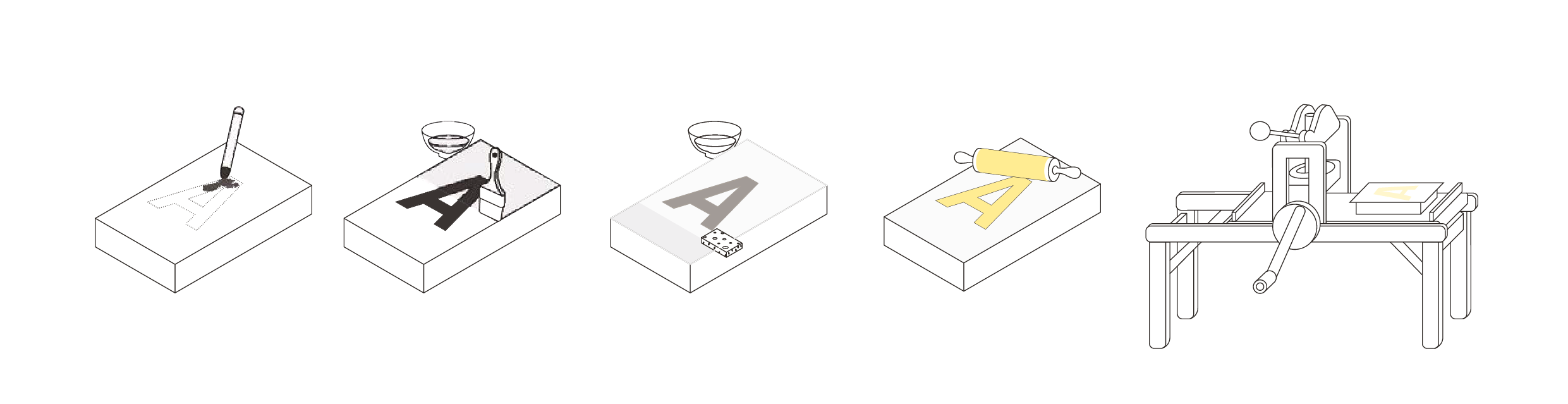

The main feature of lithography, which is based on the differing chemical properties of ink and water, is that the printed parts and the blank parts are on the same plane. The process requires the use of a particular type of porous limestone on which the image is drawn using a grease pencil and then immersed in water. While the undrawn parts are covered in a film of water, those drawn in grease repel the water; when inked, only the previously drawn parts take up the ink. When the plate is pressed, the ink is transferred to the paper. In colour lithography, a separate plate is used for each colour.

Lithography was the precursor to offset printing, which replaced limestone with a metal plate carrying the text and images. This plate is placed on a cylinder and inked. The inked image on the plate cylinder is then transferred (“offset”) onto another cylinder covered with a rubber blanket. The image is then finally transferred to paper, which is passed between the blanket cylinder and an impression cylinder. Thanks to another technique called phototypesetting, it is possible to reproduce images on plates with extreme precision.

Today, offset printing is the most commonly used system for large-volume printing.

Screen printing

From the Latin seri, “silk”, and the Greek γράφειν, gràphein, “to write”

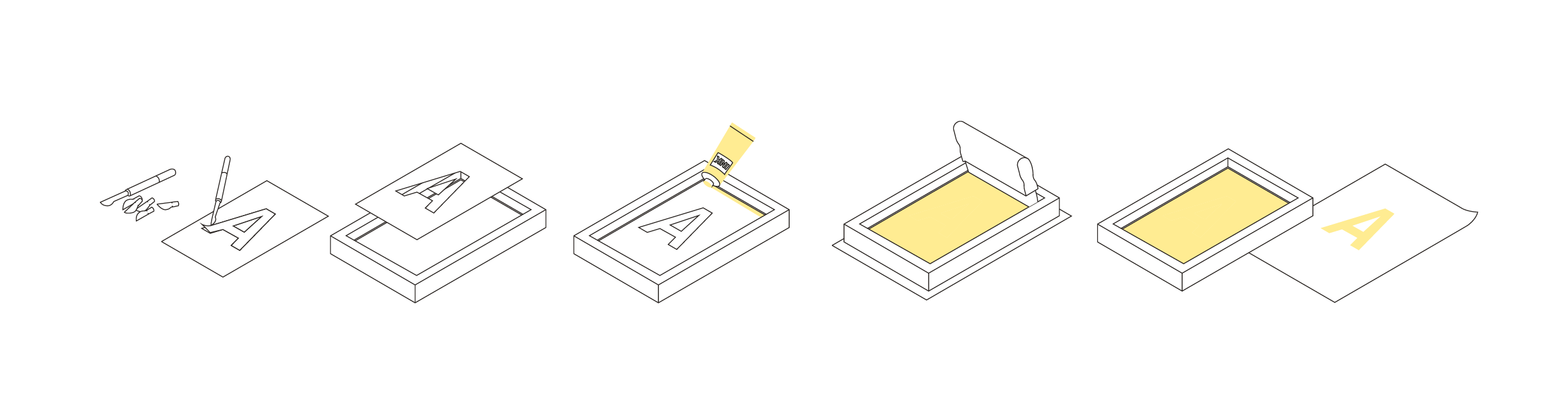

Serigraphy, or screen printing, is a technique that uses a fabric screen as a matrix from which ink is transferred onto a substrate.

Although the technique was introduced to Europe from the Far East in the Middle Ages, only recently has it gained widespread use.

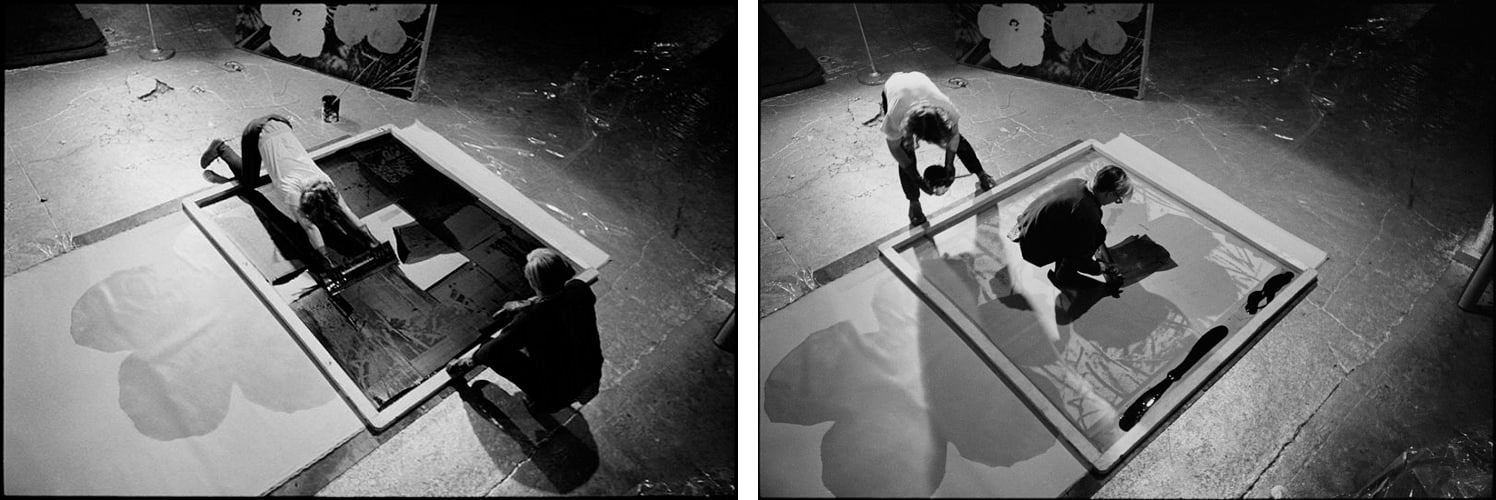

Originally silk mesh, today the screen is made from nylon or other synthetic fibres. It is covered with an impermeable emulsion in specific areas so that ink can only permeate the holes in the mesh that have been left uncovered, passing through to the substrate below. Ink is pushed through the screen using a bar called a squeegee that has a rubber edge which presses against the screen. Printing in more than one colour requires a separate screen for each.

The huge advantage of screen printing is the possibility of printing on a vast range of substrates. That’s why the technique is used both for small-scale handmade production (check out this article if you fancy giving it a try) and for industrial-scale printing of road signs, mirrors, furniture, electrical appliances, sporting equipment, shoes, bags and more.

Screen printing machines at Marimekko, Helsinki. Photo by Erin Dollar.