Table of Contents

Osamu Tezuka, widely considered the most important mangaka in the world, was born in Toyanaka in Osaka Prefecture on 3 November 1928. He was a true pioneer: without him manga and Japanese anime would not have its unmistakable look. For this reason, he is known as the ‘god of manga’, and his techniques laid the foundations for the medium and revolutionised an entire sector.

From the typical ‘big eyes’ of Japanese manga characters (most likely inspired by Western cartoons like Betty Boop and Mickey Mouse) to inventing ‘story manga’ (comics with long plots that develop over multiple chapters), Tezuka is without a shadow of a doubt the most important Japanese cartoonist and animator of all time.

He was extremely prolific: it is estimated that he produced over 170,000 comic strips and more than 700 books during his career, as well as dozens of animated films.

Childhood and war

Osamu Tezuka’s metal factory-worker father and housewife mother shared a keen interest in art, cinema and animation. At the age of five Osamu moved with his parents and brothers to the city of Takarazuka, where his mother often took him to the theatre, introducing him to the musicals performed by Takarazuka Revue, an all-female company that staged Broadway-style performances. These had an enormous influence on him.

When his photography-mad father bought a projector, it opened up the world of animation to the family. Tezuka devoured films like Popeye, Betty Boop and Mickey Mouse, and he became obsessed with the work of Walt Disney, which would have a profound influence on his own art. He watched the film Bambi at least 80 times (later on, in 1951, he also produced an adaptation of it for Japanese audiences).

In 1937, Japan went to war against China, and manga became embroiled in the conflict too: from 1938 the publishing industry was subject to state control. Propaganda books increased in number, to the detriment of all other publications. In 1937, at just nine years old, Tezuka decided to create his first manga called Pin Pin Sei-chan, showing he already had the makings of an artist.

At that age, the young Tezuka was also an avid reader of the stories published in periodicals. He was influenced by the comics of Suiho Tagawa, whose work Norakuro described an anthropomorphic dog living a soldier’s life, with humorous storylines that slowly became steeped in propaganda.

Tezuka was also mad about insects, space and biology. World War Two was raging as Tezuka was finishing primary school, and particularly from 1941, when Japan started playing an active role in the conflict. Tezuka’s father enrolled in the army. Memories of those years, including air raids and civilian massacres, would remain permanently etched in the artist’s mind, and he often narrated the horrors of war in his works.

At middle school, Tezuka suffered a serious form of fungal infection in his arms, and it was feared that they would need to be amputated. When the doctors managed to cure him, and effectively saved his life, he began to harbour the dream of becoming a doctor and helping others.

Early work and debut

In 1945 he officially enrolled at the Faculty of Medicine in Osaka, but he continued his artwork on the side. His first publication came in 1946: he sent some of the manga he had drawn during the war to the Mainichi School Children’s Newspaper. Readers loved his style,and he was commissioned to create his first official manga, The Diary of Ma-chan, which was highly successful in Osaka.

Later in 1946, Tezuka joined the Kansai Manga Club in Osaka: a group of young, talented mangaka. Here he met the expert manga artist Shichima Sakai and drew his first manga to reach a wider audience, New Treasure Island (1947). Despite a few issues and having to make some changes to the story, the work was a great success, becoming the first postwar long-story manga. It sold 400,000 copies at a time when even food was scarce due to the effects of the war.

Despite his success, Tezuka was still earning very little, but he continued to work on his comics. While studying he also devoted himself to the piano, with good results, and to theatre. He graduated in medicine in 1951, but realised he would have to choose between a career as a doctor and manga. He opted to go down the artistic path, but his aim was always to create stories that would help make the world a better place.

Early successes: Kimba the White Lion and Ambassador Atom

At this point, Tezuka was producing a ceaseless stream of work: as well as his sci-fi trilogy Lost World (1948), Metropolis (1949) and Next World (1951), in 1950 he created what would become one of his best-known series: Kimba the White Lion. This coming-of-age novel set in mid-twentieth century Africa was serialised in the Japanese magazine Manga Shōnen between 1950 and 1954.

It describes the life of a small lion who has lost his parents and has to become king of the jungle, facing ruthless humans and various perilous situations along the way. It tackles the coexistence of different species and the relationship between humans and nature, two themes that appear frequently in the master artist’s work.

Kimba the White Lion was turned into an anime series of the same name in 1965, and the series is still very popular today. It was the first Japanese anime to be produced in colour and was also at the heart of a dispute with Disney, as the enormously popular 1994 film The Lion King has some notable similarities to Tezuka’s work.

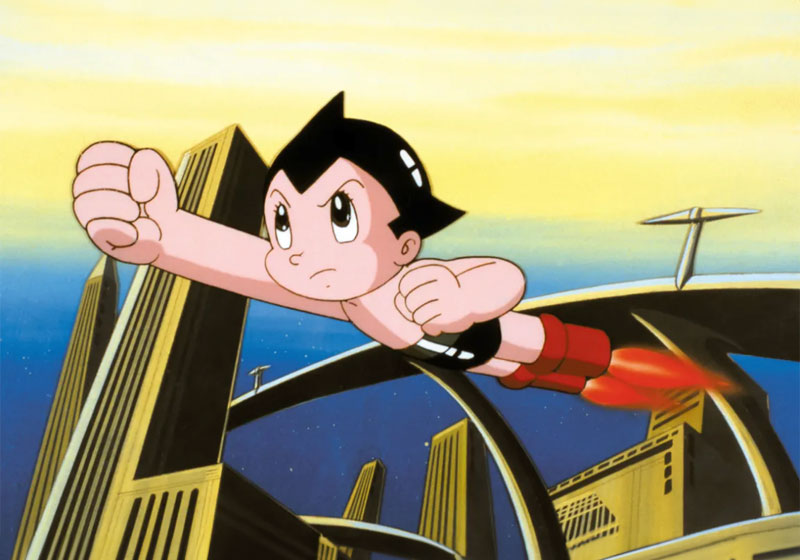

Kimba was a great success, and this did not escape the notice of the publisher Kabunsha, which at the time produced a well-known magazine called Shonen. It was in this magazine that Tezuka published what is probably his most famous work, best known as Astro Boy, starring a small robot called Atom.

Atom, also known as Ambassador Atom and Captain Atom, first appeared as a secondary character in the manga series Atomu Taishi, which was serialised between 1951 and 1952. The character’s name, which would become iconic both in Japanese culture and further afield, is a nod to the research into nuclear energy that was a key topic during the 1950s. Tezuka took inspiration from Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio when creating his most popular character: Atom is built by Dr Tenma, the science minister of a futuristic Japan, who builds the most advanced robot of all time following the death of his son.

Atom has the strength of 100,000 horses and powerful weapons that help him to destroy his enemies on Earth. However, Tenma notes that Atom cannot grow, and that a robot cannot fill the void left by his son’s death: as you can see, the themes of Tezuka’s manga gradually became more serious and ‘universal’ over time, moving away from storytelling designed exclusively for young children (although his drawings continued to appeal to youngsters). Sales were astronomical: the 23 volumes sold in excess of 100 million copies. Astro Boy also starred in various cartoon series and animated films created by Mushi Production and later Tezuka Production, the renowned animation studio founded and directed by Osamu Tezuka himself.

Princess Knight and Phoenix

1953 was also the year another very important Tezuka manga was released: an editor from the magazine Shoju Club commissioned what would become his first manga aimed specifically at girls. This was Princess Knight, the first shojo manga ever produced and also the first to be made into an anime version, again by Mushi Production. The work made history, particularly in the way it opened up manga to a female audience, which until that point has been completely neglected.

Princess Knight tells the story of Sapphire, a girl born with two hearts, one male and one female. She is the daughter of the king of Silverland, whose throne can only be passed to a male heir. After a series of misunderstandings, the king decides that his daughter should inherit the throne, and she receives a double education, both as a princess and a prince, pretending to be a boy when she appears in public. She has an androgynous beauty and knows how to fight, but her secret is revealed during her coronation, so she is forced to flee. During the course of her adventure, Sapphire must contend with enemies who try to rip out one of her hearts, as she aims to return to and rule over her kingdom.

This manga displays Tezuka’s mastery of cinematic framing, with full-page panels that slow the pace of the narrative (a common feature in manga) and highlight the characters’ emotions. These are all techniques that subsequent authors have seized upon in their work.

At this point Tezuka’s life started getting complicated: he was working on several projects at once and started missing his deadlines, with publishers always at his throat waiting for new panels.

He sorted himself out with the help of a series of assistants, and in 1954 began what is now considered his magnum opus, Phoenix, which the artist himself described as his ‘life’s work’. The story of how it came to be published was long and tortuous: the first Phoenix story, Dawn, was published immediately after the end of Kimba the White Lion in the magazine Manga Shonen, but the publication then folded, leaving the comic unfinished. Tezuka returned to it in 1957, but it was only in 1967 that Phoenix really saw the light of day, in a magazine created by the artist himself: COM.

Tezuka returned to Phoenix (though he would also go on to work on very important titles such as Black Jack and Buddha) in response to the Gekiga movement and its artists, who published their work in the seminal magazine Garo. The Gekiga movement (the name literally means ‘dramatic images’) was founded by Yoshihiro Tatsumi and sought to provide an alternative to the more ‘commercial’ manga aimed at children and young people, producing works designed for an adult readership. The Gekiga group also published a history-making manifesto of their objectives.

Tezuka, the most famous and highly paid mangaka of the age, was not about to watch from the sidelines, and he created a series of works specifically for a more demanding audience. In total, Phoenix comprises 12 stories, divided up into 11 books published between that year and 1988: Dawn, Future, Yamato, Space, Karma, Resurrection, A Robe of Feathers, Nostalgia, Civil War, Life, Strange Beings and Sun. It is an epic work: each book contains self-contained stories set in different time periods, both past and future. The star, as the name suggests, is a phoenix, a mythological creature that travels through a series of comic and tragic stories, set everywhere from outer space to feudal Japan. The overarching theme is reincarnation and ultimately the search for immortality, and the work contains the author’s reflections on existence. Unfortunately, it was left unfinished on the artist’s death.

Maturity: Message to Adolf

It would be practically impossible to list all the manga and anime projects that Tezuka worked on in this article – there simply wouldn’t be space. However, one work that definitely deserves a mention was first released in 1983: his most mature creation Message to Adolf, a manga series that continued until 1985 and which many people consider his masterpiece.

The story simultaneously follows the lives of three people called Adolf: a Jewish boy called Adolf Kamil, a German boy called Adolf Kaufmann and Adolf Hitler. It is a complex, masterfully drawn work, set during the Second World War and depicting the madness of war and Nazism, and especially the senselessness of violence.

Here Tezuka completely abandoned the trademark caricatured style of his earlier work and instead embraced a more realistic drawing style and a more structured panel division that prioritised the storytelling (although the characters remained highly expressive).

Osamu Tezuka’s legacy

Osamu Tezuka died on 9 February 1989. He was drawing until his final days, and left some work unfinished (Ludwig B and Neo Faust). He left behind him an immeasurable legacy for the comics world, not only shaping the Japanese comic book landscape, but also influencing generations of artists across the globe.

His skill in blending compelling storytelling, emotional depth and a unique visual style created a benchmark for excellence in the sector. Astro Boy paved the way for the arrival of the famous Japanese robots. And nor was his legacy restricted to his artistic contribution: Tezuka also introduced various complex themes and social and philosophical issues.

Osamu Tezuka’s influence lives on and prospers today, both through his enormous body of work and through the constant inspiration he provides to anyone who wants to start drawing comics.