Table of Contents

On 26 June 2020, we lost one of the most talented designers of the last century. At 91 years of age, on his birthday, Milton Glaser passed away. He had enjoyed a long and prolific career imbued with a deep passion and respect for his vocation.

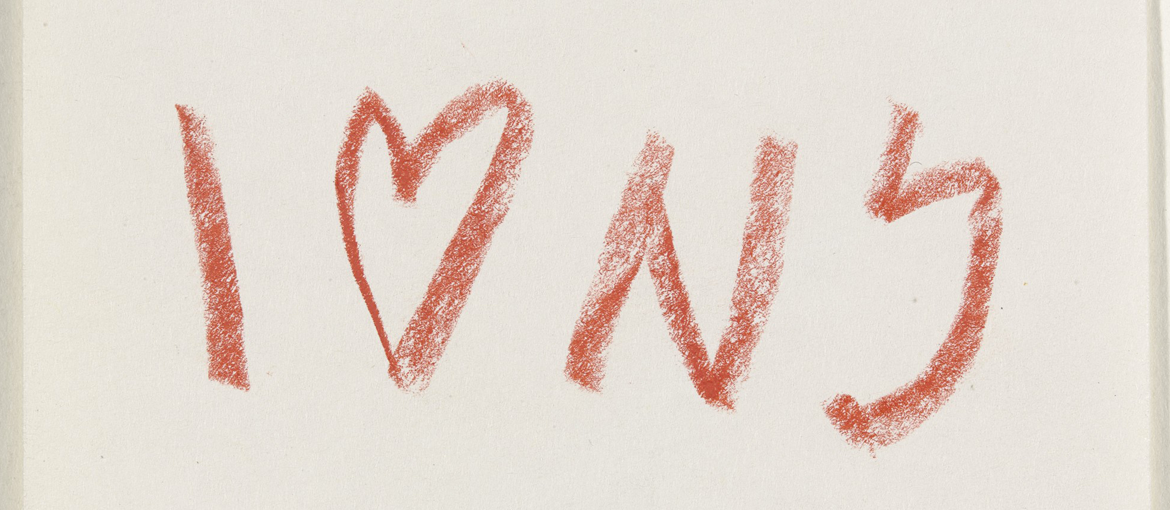

Milton Glaser was born in 1929 in New York, where he lived his whole life, bar a few years. His most famous piece of work, which he did pro bono, shows the strong bond he felt with this city. Approached in 1975 by ad agency Wells Rich Greene to create a logo to promote tourism in the city and state of New York, Glaser had a eureka moment in the back of a taxi. In a scene straight out of Mad Men, he sketched out his idea there and then on the back of an envelope: three letters and a symbol – an early precursor to today’s emoticons – are all it took to make one of the most memorable and ubiquitous logos of all time.

The brief and only time Milton Glaser lived outside of New York, he spent in Italy. He would develop a lasting bond with the country, absorb its teaching and influences, and develop close working relationships with major Italian firms and institutions.

An Italian education

Ever since he was a little boy, Milton Glaser was obsessed with drawing, which he soon realised he had an unusual talent for, one appreciated by classmates, who would ask him to draw anything and everything.

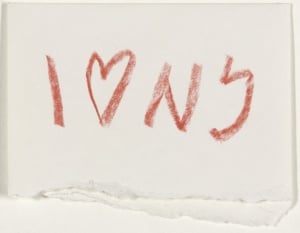

After graduating from the Cooper Union School of Art in New York, Milton Glaser won a Fulbright scholarship to attend the Academy of Fine Arts of Bologna, where he honed his drawing technique. Here, he had the chance to study etching under the tutelage of artist Giorgio Morandi, whose calm, humble and hard-working personality would influence him greatly. “With him I learnt one thing: what a student can learn is not so much a technique, style or trick, but rather what the teacher is.”

In Bologna, Glaser also indulged his passion for Italian renaissance painting, particularly the work of Piero della Francesca.

Several decades later, during a trip to Italy in the 1990s, he produced a series of watercolours for an exhibition marking the 500th anniversary of Piero della Francesca’s death.

The Italian experience of his youth was not just a parenthesis for Glaser, but a formative influence on the rest of his life. “The spirit of Italy, the Renaissance, the attitude towards food, architecture and everything else, is so pervasive in everything I do that I cannot separate it from everything else.”

Italian commissions

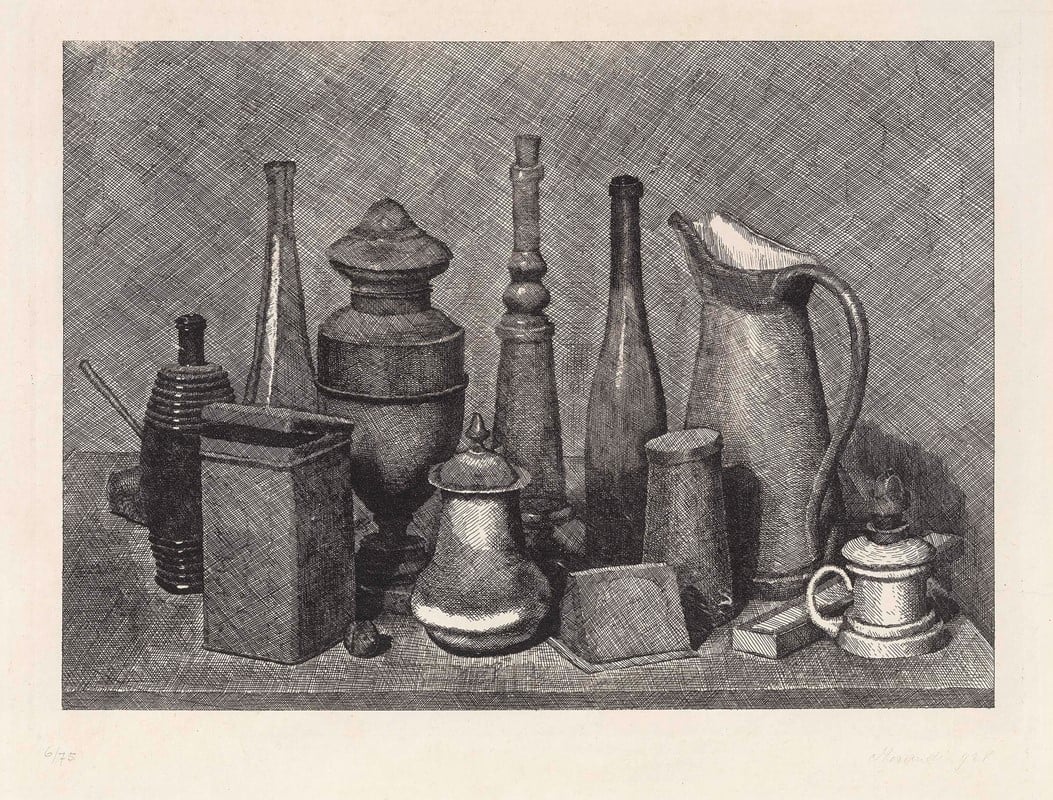

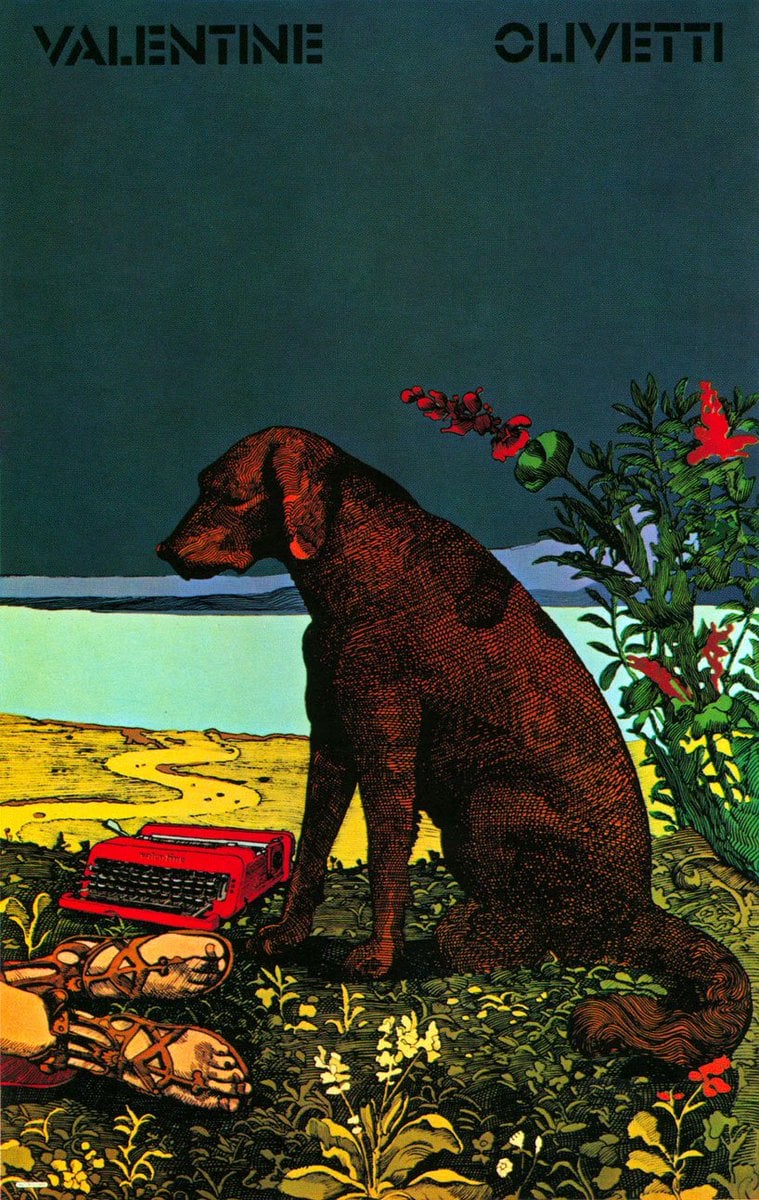

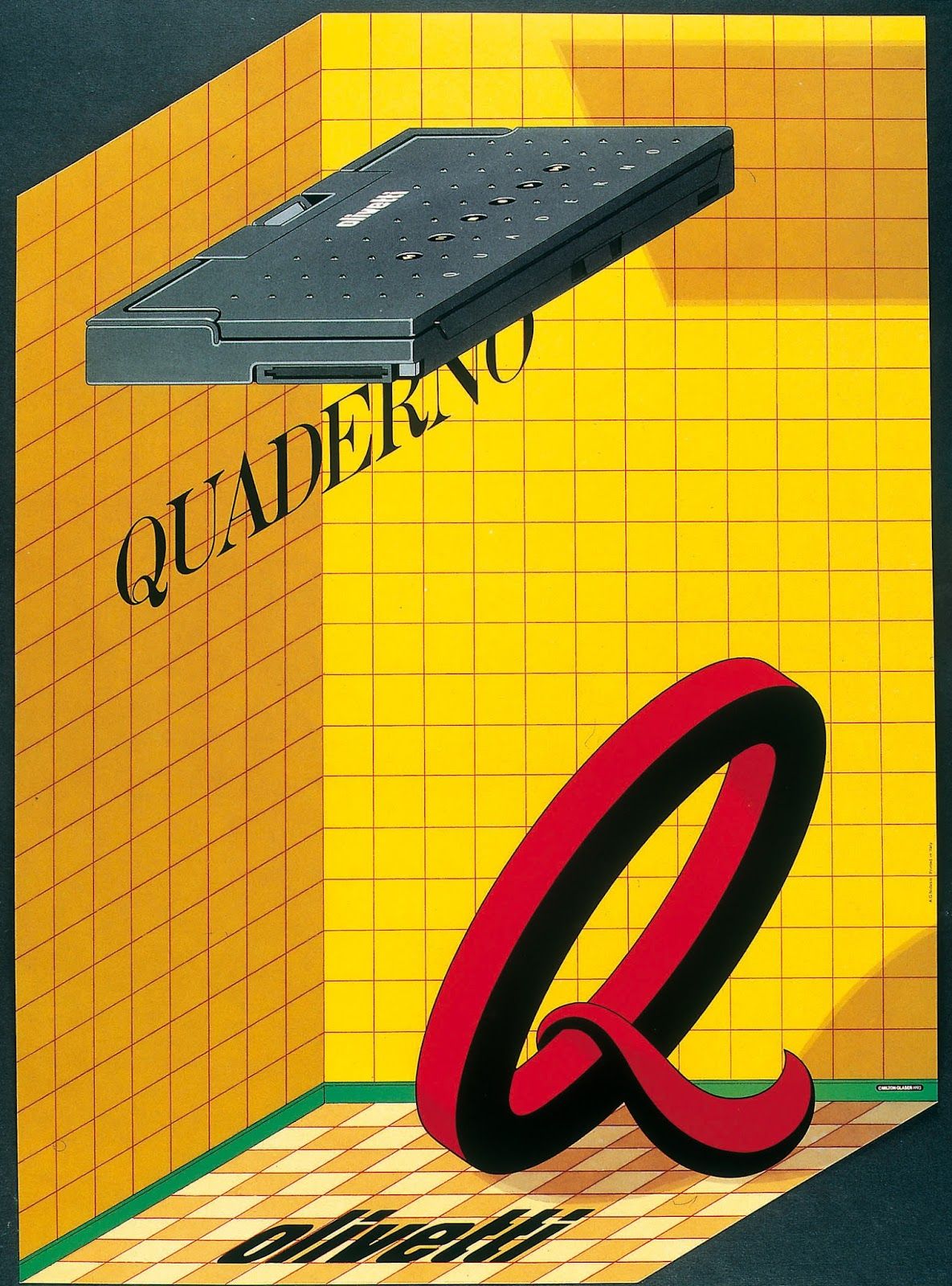

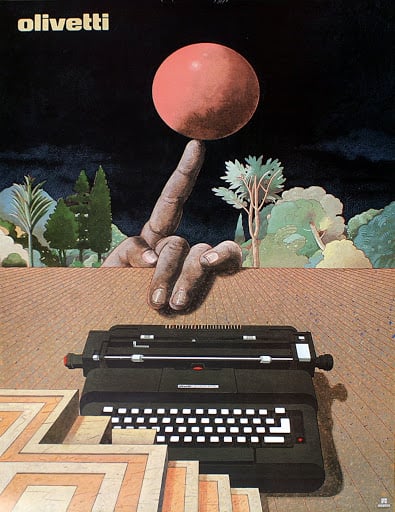

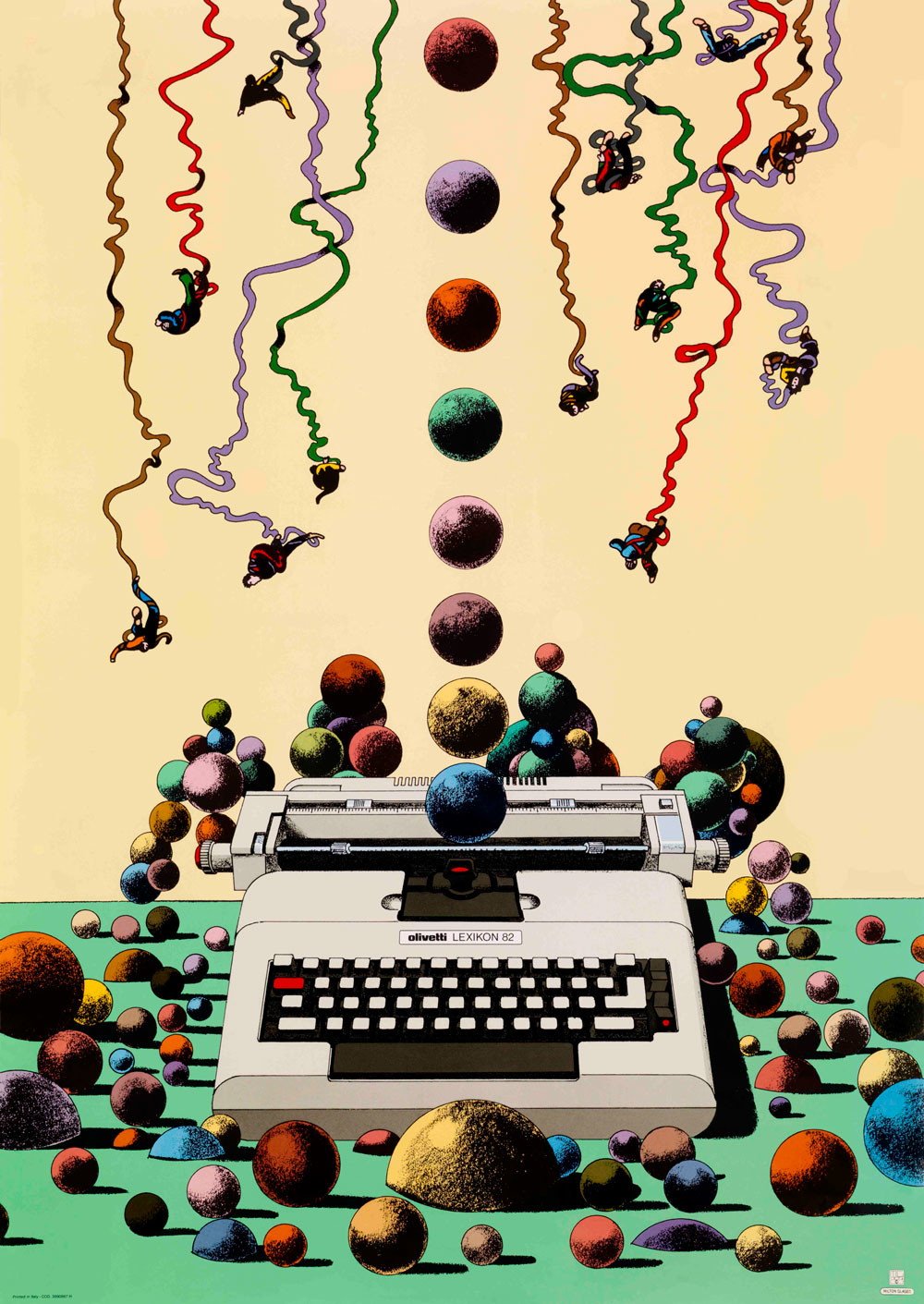

Undoubtedly, it was thanks to Glaser’s familiarity with and sensibility towards Italian artistic tradition that he was able to embark on fruitful collaborations with some of the most renowned Italian companies and institutions. One of these was Olivetti, for whom the Glaser designed several posters.

In his poster for the Olivetti Valentine typewriter (1968), Glaser uses the detail of the mournful dog from Piero di Cosimo’s painting The Death of Procris. Between the dog and the feet of the nymph lies a bright-red Valentine typewriter. This poster perfectly encapsulates the designer’s blend of renaissance sensibility and American pop culture: the subject is humanistic, the outlines and the areas of shadow are created using etching, but the stylistic use of oversaturated spot colours, and above all the choice of subject for an advertisement, make it a unique piece of work. “No other company in the world would have tried to sell typewriters like this,” said Glaser about his collaboration with Olivetti.

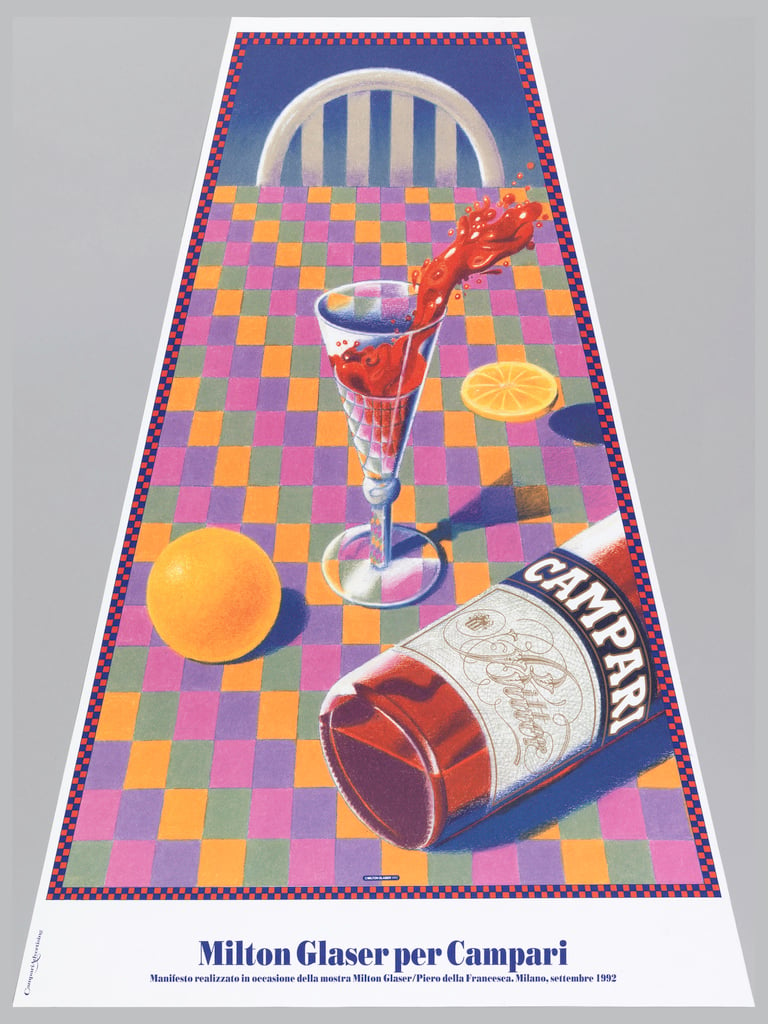

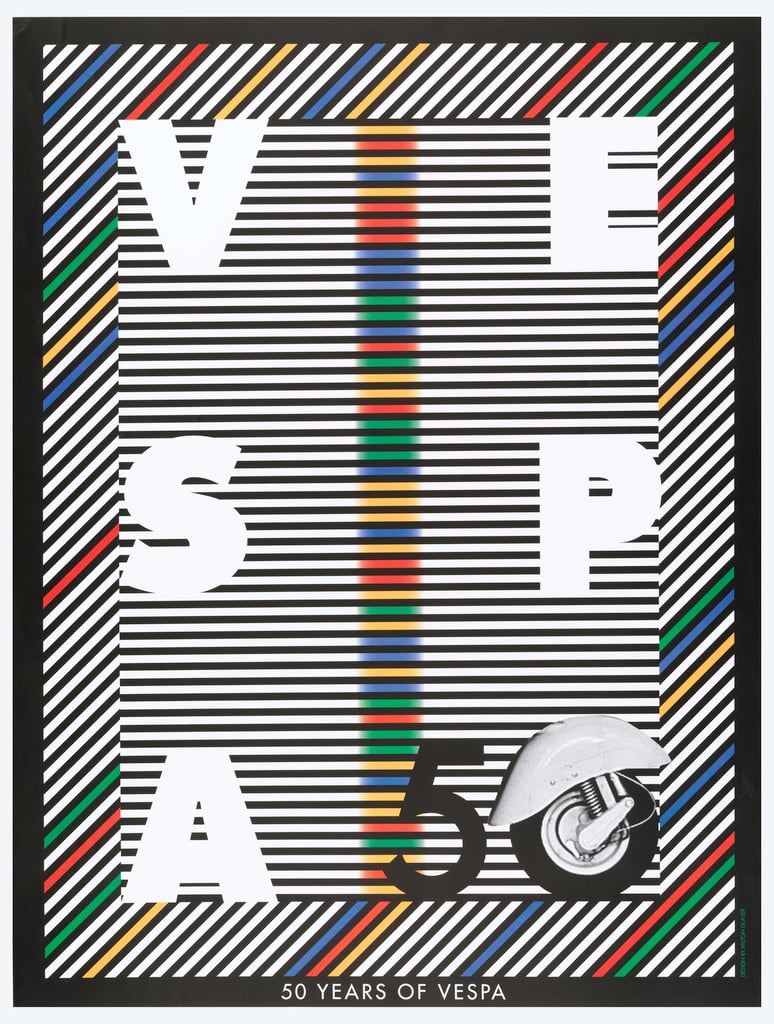

There would follow collaborations with Campari, sponsor of the Milton Glaser Piero della Francesca exhibition, Sammontana (he created their famous logo) and Vespa, for whom he produced a poster to mark the brand’s 50th anniversary. This time, Glaser eschewed illustration and instead used simple graphic elements in a dynamic composition that alludes to the colourful speed of a Vespa.

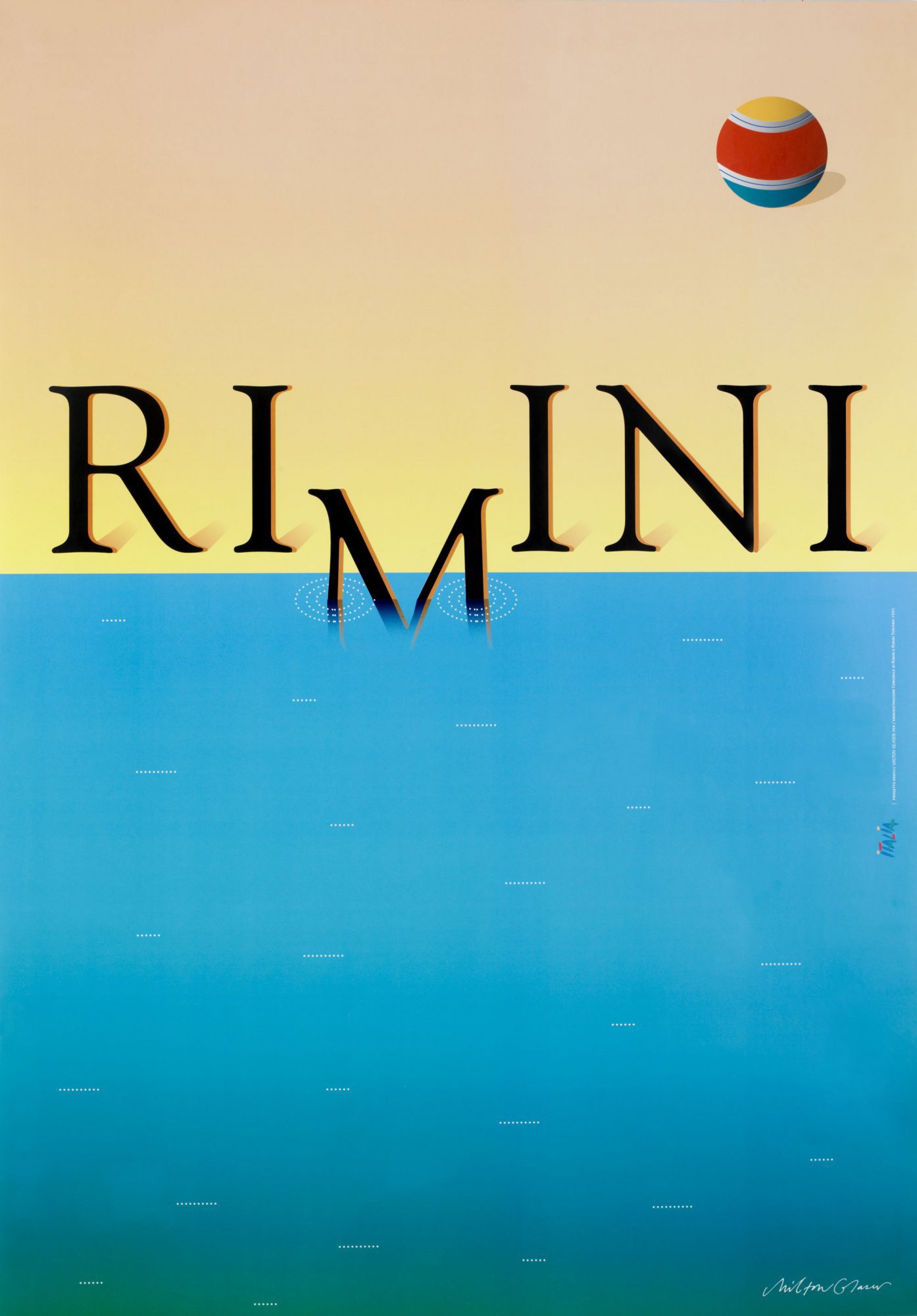

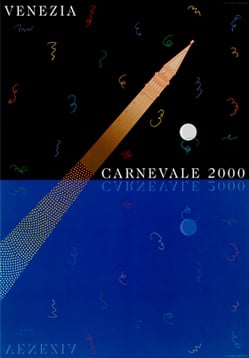

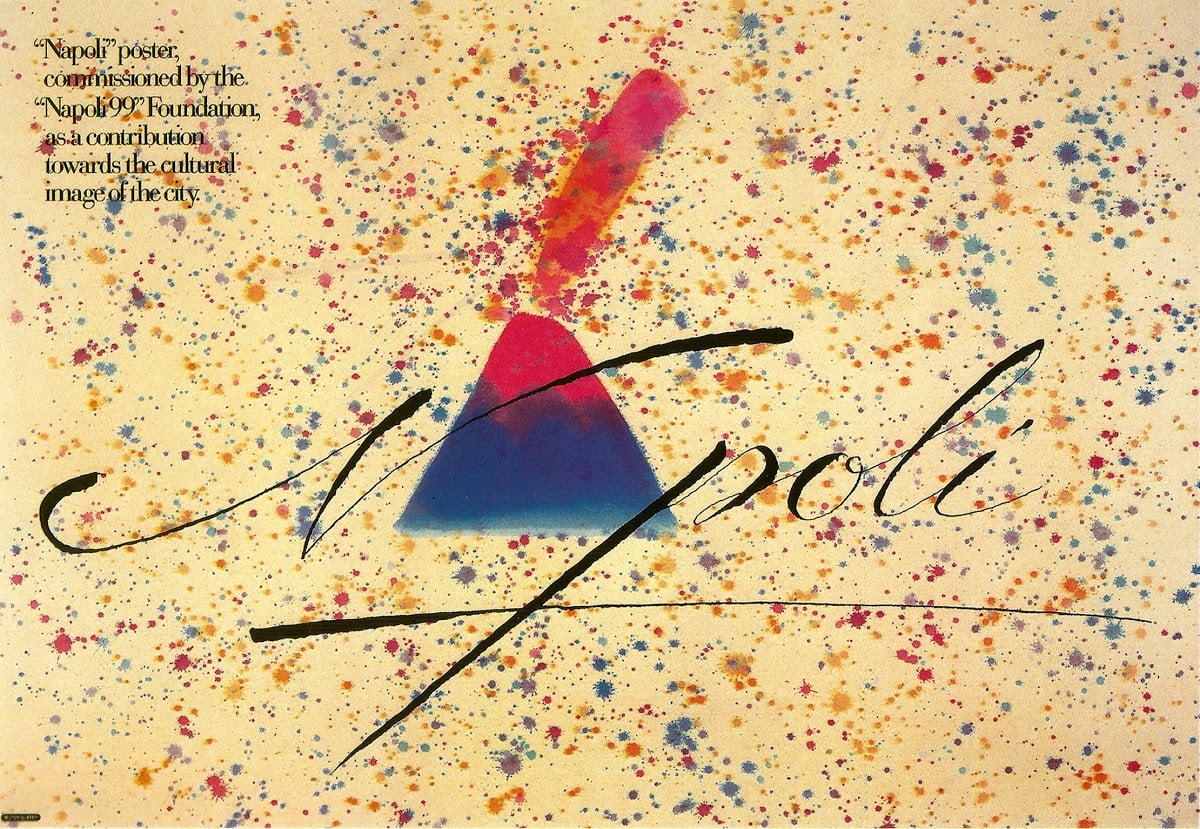

Italian commissions weren’t limited to the private sector. A number of cities asked Glaser to design posters promoting them as tourist destinations, including Naples, Rimini and Venice, for whom he designed posters for both the Biennale and the carnival.

Every poster has its own identity, it’s the fruit of the context in which it’s born. For Naples, the composition centres around an erupting Vesuvius that serves as the “A” in “Napoli” and is surrounded by splashes of colour created using the “dripping” technique made famous by Jackson Pollock. There’s a completely different feel for the poster created for Rimini, where the calm of a sunny day at the beach reigns. Set against a background of almost flat colours, the “M” of Rimini takes a dip in the waters of the Adriatic, while a beach ball lies stationary in the top right corner. For Glaser’s Venice carnival poster, the composition once again consists of a calm sea depicted in spot colours, but this time the mood is more lyrical and dreamlike: the water is a mirror that reflects a full moon and the typography, and through which St Mark’s bell tower shoots towards the sky like a rocket.

Exhibitions in Italy

Milton Glaser’s relationship with Italy has been celebrated with several shows.

In 1989, two exhibitions of Glaser’s work were held: a personal show of his posters at Vicenza Civic Art Gallery, and another at the Bologna’s Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna, sponsored by Olivetti and entitled Giorgio Morandi/Milton Glaser. In 1991, Glaser was commissioned by the Italian government to put together an exhibition to mark the 500th anniversary of renaissance painter Piero della Francesca.

A major retrospective of his work opened in February 2000 at the Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, in Venice, right in the middle of Carnival: it was a show dedicated to all of his work, and aimed at revealing the man behind the poster created for this incredibly important event for the city.

Glaser’s loyalty to New York remained: unrivalled in terms of opportunity and diversity, and constantly changing, it was the only place that the designer lived and worked. The personality and work of Milton Glaser were forged in New York, and in turn helped to redefine the city. This makes it all the more fascinating to see how, in his work, Glaser absorbed and reinterpreted Italian influences, which have their roots in the Renaissance and ancient traditions, in an American culture based on modernity and change.