Table of Contents

The life and work of Will Eisner, considered by many as the inventor of the graphic novel and one of the greatest comic-book artists of all time.

Contents

Masters of comics: Will Eisner

Partnership with Jerry Iger and the first publications

The birth of The Spirit

Drawing for the US Army and a farewell to comics

A Contract with God and the birth of the graphic novel

The monumental legacy of Will Eisner

Will Eisner was born in Brooklyn, New York, on 6 March 1917 into a family of Jewish immigrants. His father was an aspiring painter who passed on his love of drawing and illustration to his son from an early age. Young Eisner was often the victim of antisemitism, even at school. His family was poor and their situation became even more precarious after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed.

By the age of 13, Eisner was already working selling newspapers, but he continued to attend DeWitt Clinton High School, where he drew for the school paper (The Clintonian) as well as literary magazines. Eisner then went on to study art and his contacts got him work drawing for advertising: he completed his first comic in 1934, at the age of 17.

Called Sketched from Life, it was created for an advertising brochure.

In 1936, his school friend Bob Kane (who would go on to invent the Batman character with Bill Finger) suggested pitching cartoons to a comic book called “Wow, What A Magazine!”, which was a collection of comics in tabloid format and reprinted in colour.

There he met the magazine’s editor, Jerry Iger, with whom he would go on to found Eisner & Iger, an agency that produced and sold comics to various publishers. One of the first of these was the Hawks of the Seas series for Quality Comics, in which Eisner was quickly able to hone his craft. Eisner & Iger would employ artists such as Bob Kane and Jack Kirby, who between them would go on to create legendary characters such as Captain America, The Fantastic Four, Thor and Hulk.

In 1939, Eisner was commissioned to create the character Wonder Man, but it was quickly blocked by DC Comics because it was too similar to Superman. This was Eisner’s only foray into the superhero universe, but it would be a formative experience for the cartoonist who would become a comics pioneer in a career spanning seven decades.

Eisner was influenced by comics artists like Milton Caniff, Al Capp, E. C. Segar and George Herriman, but over the years, he too influenced other cartoonists as well as authors and directors like Orson Wells. And, above all, Will Eisner would be credited as the godfather of the graphic novel as we understand it today.

The birth of The Spirit

In 1939, Will Eisner ended his collaboration with Jerry Iger and began a new and productive partnership with the head of Quality Comics, Everett M. “Busy” Arnold. It was boom time for comics, especially in newspapers, and the publisher wanted to jump onto this lucrative bandwagon.

Will Eisner was 23 when he created The Spirit, a masked crime fighter. The series followed the conventions of American comics but was published in a weekly supplement for newspapers. The Spirit, upon the insistence of its creator, is not another superhero: beneath the mask lies criminologist Denny Colt, believed dead and now working incognito. He doesn’t have superpowers, unlike Superman and the others, but is described by Eisner as a “middle-class crime fighter“.

Published between 1940 and 1952, The Spirit is today regarded as one of the most important comic-book heroes of all time, so much so that in 2008 it was also turned into a film of the same name written and directed by Eisner’s friend Frank Miller.

With The Spirit, Eisner began experimenting with the page: the first stories were somewhat conventional, with no more than 11 panels each and drawings that rarely strayed beyond the pre-set grid.

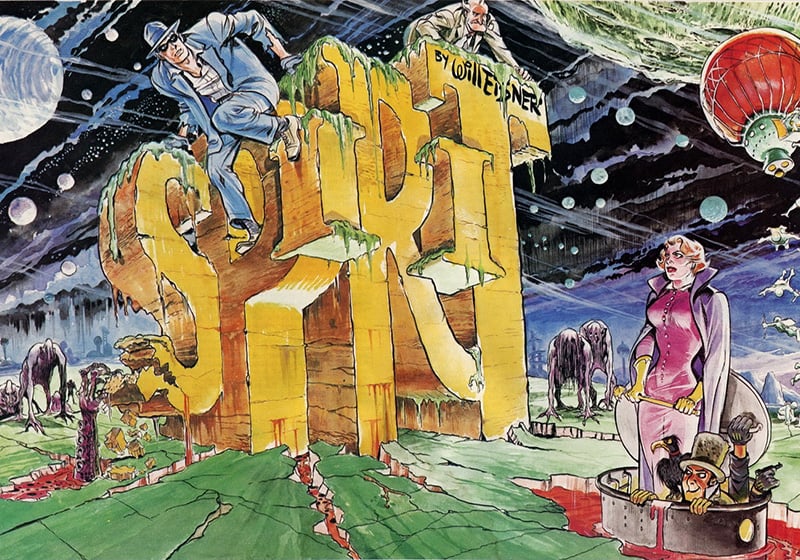

But with subsequent stories, beginning in the second half of 1940, Eisner began to play with the page more. From the introduction of splash pages (a page with one big panel, which are today typical in American comics), to imaginative title pages that presented the words The Spirit in a different form each time: these pages introduce the story’s setting and characters, with the title’s lettering actually incorporated into the physical environment depicted in the panels.

With the weekly publication of The Spirit from 1941, Eisner dared to push things further. The page grid was no longer a boundary for him and comic-book conventions went straight out of the window. Even the plots became more complicated and were no longer linear, leading to complaints from the editor-in-chief of the Philadelphia Record, one of the big newspapers that published The Spirit at the time.

Drawing for the US Army and a farewell to comics

In 1942, as the Second World War raged, Will Eisner was called up to serve in the US Army. The Spirit continued to be released, but was drawn by different artists. Eisner was assigned to the camp newspaper at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland and then to the Pentagon. This is where he began drawing comics and illustrations for the army. His most famous work from this period is the character Joe Dope, a klutzy soldier who featured in illustrations for equipment maintenance.

At the end of 1945, Eisner returned to drawing The Spirit, adopting a less realistic aesthetic: the war years had influenced his style.

The Spirit ceased publication in 1952. At this point, Eisner decided to leave comics behind to concentrate on more commercial work. This did, however, include some comics, mainly with American Visuals, the studio that he founded during the 1940s. It wasn’t until the 1970s that he would return to regularly drawing comics.

Only recently, the “lost years” of Will Eisner’s work have been published, that is to say the two decades between 1951 and 1971, thanks to Eddie Campbell’s book. In this period, he once again drew comics for the US Army: he worked on a magazine called PS – The Preventive Maintenance Monthly, which used simple, understandable and entertaining drawings to show soldiers how to maintain their vehicles and weapons. He also resuscitated the character of Joe Dope in his trademark caricatural style.

A Contract with God and the birth of the graphic novel

In 1972, Eisner officially left American Visuals, which was on the verge of bankruptcy. He also parted ways with the US Army and PS Magazine. These were the years of American underground comics and rebellion. Nearing 60, Eisner had to decide what to do with his life. A remark from his wife Ann stirred something inside him: “Why don’t you finally do what you always wanted to do?”.

His initial idea was to go back to doing comics, but the audience had radically changed by now. The average teenage comic reader from the 1940s was now in their 40s and Eisner realised that the time was right to try something more adult, a new approach to comics. Determined to take this path, Eisner even refused Stan Lee’s offer to become editor-in-chief at Marvel.

In 1978, Eisner released what many consider to be the first graphic novel. (Although similar works were published in the United States from the 1950s onwards, none had the power of Eisner’s masterpiece). It was called A Contract with God and it was essentially a novel created out of images.

Eisner began to think of comics as sequential art, a concept that he would later expand upon in his books Comics and Sequential Art and Graphic Storytelling.

A Contract with God is arranged into episodes and tells four stories about men and women, with decidedly adult themes. From the street singer who wastes the opportunity of a lifetime to Frimme Hersh, a man who decides to unilaterally sign a contract with God, but who becomes a miserly landlord when he believes he has been abandoned by God.

In later years, Eisner produced many more graphic novels that told the stories of immigrants in New York, especially the Jewish community. These included The Building, A Life Force and To the Heart of the Storm. Published in 1991, the latter is one of the author’s most important works, addressing racism in the United States during the war. Eisner’s Jewish roots often informed his work, including Fagin the Jew (2003), a revisitation of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, and The Plot: The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (2005), in which he tells the story behind the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a document that purported to be a secret plan by Jews to take over the world, but which was in fact fabricated by Russian ultra-nationalists.

The monumental legacy of Will Eisner

Will Eisner continued drawing and creating until a few days before his death at the age of 87 in 2005. His signature half-tones and strong contrasts, his perfect balancing of captions, dialogue and images are all still there on his very last pages.

A true master of his craft, his work had an enormous impact on everything and everyone that came afterwards. He innovated with drawing techniques, framing and page layout, as well as the use of Indian ink to create sharp contrasts.

In his stories, the style could shift from realism to parody, with sequences of images precisely designed to suck the reader right into the story. His work often had the atmosphere of film noir, with storylines that posed existential questions, especially those of his graphic novels.

So influential was he for the “ninth art” that he lends his name to one of the world’s most prestigious prizes for comics, the Eisner Awards, first held in 1988. He personally officiated at the annual ceremony until his death. Will Eisner was a grandmaster who left a vast body of work that will continue to be read and studied for years to come.