Table of Contents

New ideas, entrepreneurial ventures, unbelievable oversights, patents and inventors… these are just some of the ingredients of the stories we’re about to tell: today, we’re bringing you five machines that, starting in the 19th century, revolutionised the printing world.

Printers, scientists and inventors have never stopped trying to improve Gutenberg’s incredible invention: movable-type printing. Ever since, ingenious machines have been developed to facilitate various printing-related activities, such as page typesetting, typeface creation and, of course, printing itself.

Linotype, the rotary press, offset printing and Lumitype are just some of the successful inventions that have helped to define what we know as “printing” today. These machines have allowed us to print in greater volumes, more quickly and more efficiently, taking us from the industrial revolution to the digital era.

The rotary press

Freshly printed newspapers racing through huge rollers at lightning speed: it’s an image familiar to us all. But, although the rotary printing press is etched in our collective imagination, this invention appeared relatively late in the history of printing. In fact, it was only in the 19th century that people started thinking about a new system to replace the printing press, which had essentially remained the same since Gutenberg’s era.

The idea is simple: replace all the flat printing surfaces with rotating cylinders. One cylinder holds the printing plate, and the other the paper. It might seem like an insignificant invention, but switching from a flat press to a cylindrical one revolutionised the printing world and made it much easier to harness other technological breakthroughs from the industrial revolution: first steam power, and later electricity. Everything became bigger, faster and more efficient, and printing became an industrial process.

We got there gradually, through an accumulation of intuitions.

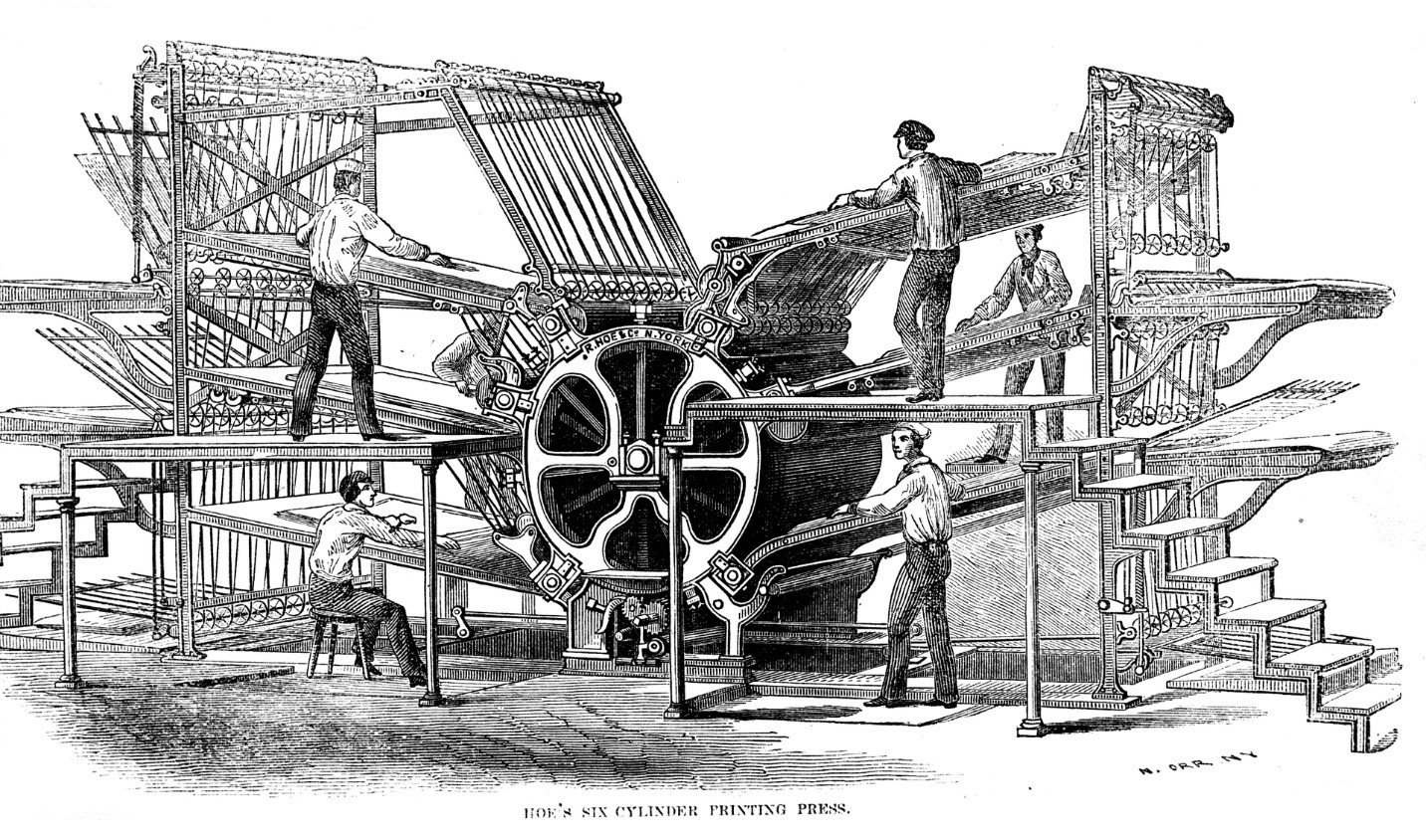

In 1814, German inventor Friedrich Koenig devised the first steam-powered flatbed cylinder press, which enabled printing speeds to increase from 300 to 1100 sheets an hour. Thirty years later, American Richard March Hoe took this invention and improved upon it to create the first true rotary press. Shortly afterwards, he replaced single sheets with huge rolls of paper.

The first rotary press of this kind was installed at the Times of London in 1870 and was able to produce around 12,000 newspapers per hour. Today, some presses can print over 60,000 copies an hour, with paper moving through them at speeds of up to 30 km/h.

The offset printing press

This is the first offset printing press and it was created by accident. But we’ll get to that in a minute.

Offset printing is one of the inventions made possible by the rotary press. It uses three cylinders: the image is transferred from the plate cylinder to an intermediate cylinder covered in a rubber, and then from this cylinder onto the substrate.

But the transfer of the image to a rubber cylinder was born from… an oversight. In 1901, American lithographer Ira Washington Rubel forgot to insert a sheet of paper into the lithographic press he was using, leaving the image imprinted on the rubber cylinder that was used to hold the paper in place. When, realising his mistake, he inserted the paper between the cylinders, Rubel noticed that the image printed by the rubber cylinder was much sharper than that printed by the stone plate.

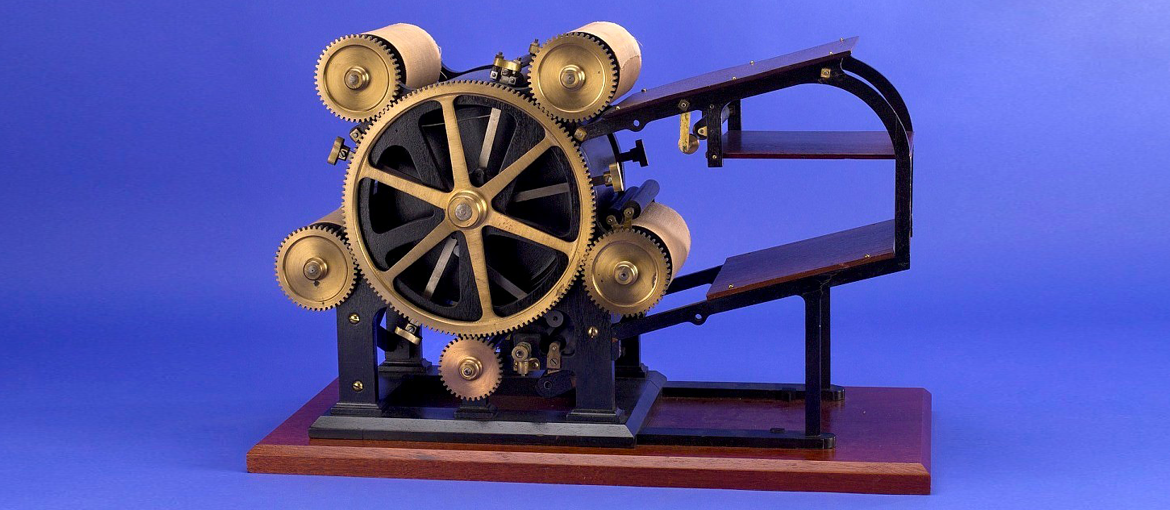

Rubel immediately understood the importance of his discovery. In a little workshop in New York, he built the first offset press based on this principle. The first model was purchased by the Union Lithographic Company of San Francisco in 1905 and sent to the west coast. But a devastating earthquake in San Francisco and a fire in the port of Oakland delayed its arrival, and it was only used for the first time in 1907. It printed around 2500 sheets an hour.

This very machine is now preserved at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington (which we talked about before, here).

Linotype

From the invention of printing to the industrial era, one activity remained unchanged for four centuries: typesetting.

From the lively workshops of 15th-century publishers to the big 18th-century printworks, the typesetter continued to work by hand, arranging one character at a time into lines in the composing stick. Once he had finished, the page was ready to be inked and printed. The typesetter then had to take the page apart and go through the same process all over again for the next page.

With the advent of steam power and the beginning of the industrial revolution came many attempts to mechanise this operation, but for years none were a success. Then linotype arrived.

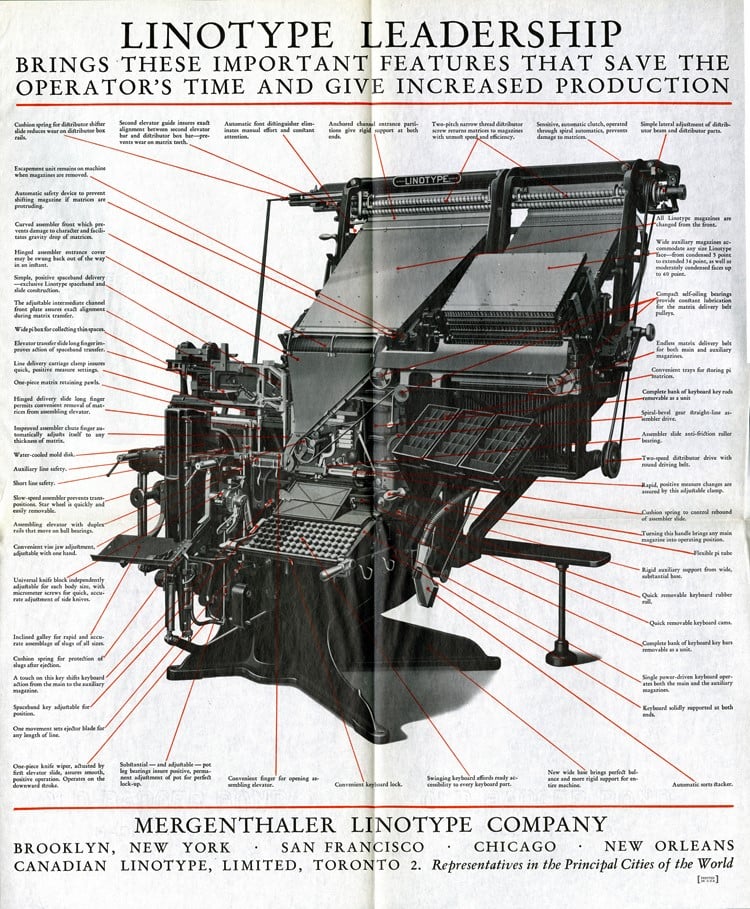

Invented in 1881 by a German émigré to the United States, Ottmar Mergenthaler, linotype (a contraction of “line-o’-type”) quickly caught on, revolutionising the world of printing.

It was the first automatic typesetting machine: it used a sort of typewriter connected to a miniature type foundry. The operator would type out the text using a keyboard, with each press of a key releasing a matrix (a mould for a character) for the corresponding letter, which would be dropped into the line of text. Once the line was complete, it was automatically carried to another part of the machine where it was cast from molten metal. The lines were then stacked together, inked and printed.

In this interesting video from the Museum of Printing and Graphic Communication in Lyon, France, we can see all of these steps in action as an old linotype machine is operated.

The first linotype machine was installed at the New York Tribune in 1886. Consisting of thousands of parts, the machine was extremely complex and would undergo many tweaks and improvement over the years.

In 1889, the linotype machine won the Grand Prix at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, and quickly spread around the world. It was only with the introduction of phototypesetting in the seventies that this extraordinary machine began to fall out of use.

Lumitype and phototypesetting

In the middle of the 20th century, the “hot metal” typesetting process used by linotype machines started to be replaced by “cold metal” typesetting. It was another revolution: phototypesetting was born. Gone were lines of type cast on the spot: typesetting was now done using a machine called an imagesetter, which produced film negatives.

The first phototypesetting machine was called the Lumitype and was invented in 1946 by two French engineers, René Higonnet and Louis Moyroud. However, the pair had to move to the United States before they could find someone interested in their invention. Baptised the Lumitype Photon, their first machine was manufactured by Lithomat in New York in 1949.

The first book to be entirely phototypeset was “The Wonderful World of Insects” and, on the final leaf of the book, appear the words: “Rinehart & Company is proud that its book was chosen to be the first work composed with this revolutionary machine…”

Phototypesetting became cheaper in the seventies and unleashed the creative energies of smaller printers: it was now possible to use a hitherto unimaginable number of fonts, in any size, while laying out text and images together was made much easier.

The computer

It was another amazing machine that sealed the fate of the phototypesetter: the computer.

From the eighties onwards, the spread of computers allowed pages to be laid out onscreen. This was made possible by two methods: computer to film, which was used to create films from which printing plates were made, and computer to plate, which enabled plates to be created directly, eliminating the entire phototypesetting process (set up, exposure and development of films, then exposure and development of plates).

Personal computers started to appear in every home, making it possible for anyone to lay out their own documents and, with the introduction of inkjet and laser printers, print them in their own home. The digital revolution had begun… but that’s another story entirely.

What will be the next machine to radically change the world?