Table of Contents

Printing is completely familiar to us nowadays, whether in the analogue form of newspapers and other printed materials, or online on apps and digital media. Written texts are ubiquitous, and personal printers allow us to transfer words to paper with great speed and ease. No wonder, then, that we are so quick to forget how inventive and widespread the printing industry once was, how significant printing (of books in particular) is as a means of cultural transmission, and how attractive those black letters can be even now.

The Leipzig Museum of the Printing Arts is responsible for the care and preservation of this heritage, as well as for putting it to practical use on a daily basis. The museum is located in the Plagwitz district in the west of Leipzig. Behind the pretty, albeit fairly nondescript, facade is an inner courtyard that reveals the building’s industrial history, with its red bricks and high windows with white wooden struts. Leipzig’s Plagwitz district was planned and developed in the 19th century as an industrial zone, and the building that today houses the Museum has an industrial history of its own, having originally served as a printing works.

A place for historical printing techniques and their preservation

While the foyer and the entrance hall are modern and fitted largely with wood, the exhibition spaces retain the old factory feel. The building encapsulates the spirit of manufacturing; you would think little of it if, at any moment, the typesetters clad in their suits and white aprons flocked to the factory floor while the foremen sat in their glass-enclosed offices. Everything is clean, functional, and minimally furnished – much like an actual factory. However, factory workers have since made way for the museum staff, who are themselves experienced or trained in printing. The employees demonstrate the machinery and explain each function, whether it be for letterpress, intaglio, or flatbed printing.

‘We want to maintain an active relationship with the significant historical heritage of the printing arts; we want this to be a place where you can experience the power of the machines first hand, but also the care and precision required for printing. And that’s why we’re so delighted that UNESCO have recognised artistic printing techniques as intangible cultural heritage.’ Susanne Richter, Director, Museum of the Printing Arts

Lithography: the predecessor to offset printing

Speaking of flatbed printing, the tour of the exhibition begins with a lithographic press in the large machine room on the ground floor. The machine weighs 12 tonnes and can produce large numbers of lithographs. In short, this involves ink from a limestone plate being transferred to the paper in such a way that only certain parts accept the ink, while others repel it. The technique is demonstrated and explained at the museum initially using a small hand press. The method was invented by Alois Senefelder and was the predecessor to today’s offset printing. Lithography increased the prevalence of colour printing in the 19th century and even the early 20th century. On its own, the stone used to print in the lithographic press weighs around 200 kilograms. The captivating final stage of the process sees the large flywheel gathering pace and the machine settling into a steady rhythm, delivering the printed sheets to the tray, where they are collected by hand.

Like the lithographic press, larger machines in the letterpress category optimised and improved the speed of the printing arts. Preliminary models provide an insight into how problems were solved over time. The early, manually operated presses are truly eye-catching. In the foyer stands a replica of a screw press made entirely of wood. A griffin, the heraldic animal of the letterpress, is the machine’s crowning glory. The successors to this model, the toggle presses, are particularly striking thanks to their ornate decorations. A metal figurine of Johannes Gutenberg adorns one such press, for example. The toggle press applies increased pressure by means of a lever mechanism. Metal gradually became the material of choice in the construction of this model, as it is more durable and is less sensitive to fluctuations in temperature and humidity.

Printing and typography go hand in hand

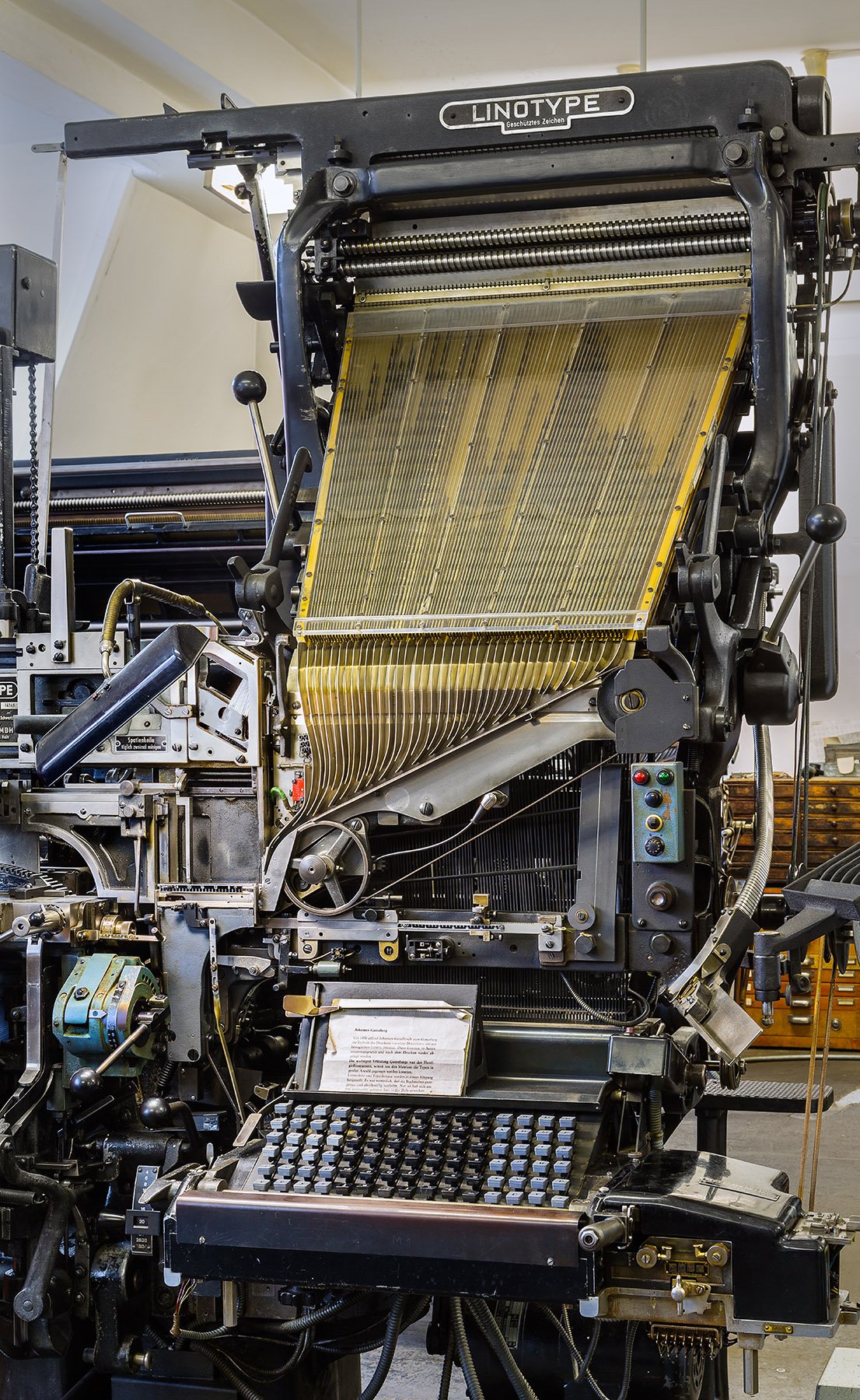

Typesetting, which is carried out at the type foundry, also demonstrates how complex printing once was. The process involves the design of a matrix that serves as a mould for the typeface. While a softer material is used for the matrices in which the mould is shaped using (hardened) steel stamps, the letters are cast with an alloy of lead, tin, and some antimony – the latter gives the characters the solidity they require. This, too, can be reproduced very faithfully. Technology enthusiasts certainly get their money’s worth – whether it be through taking in fully automated letter printing with an automatic type-casting machine, or reliving the eventual replacement of typecases by machines, which, in the manner of the typewriter, would take over the job of casting and typesetting. Visitors can learn about this technological development through the museum’s ‘Linotype’ models.

‘What always fascinates me especially about our museum is the unusual smell that fills the place. It’s a unique combination; it smells of lubricants, printing ink, machine oil. I can’t describe it exactly, but it’s very distinctive.’ Sara Oslislo, research volunteer

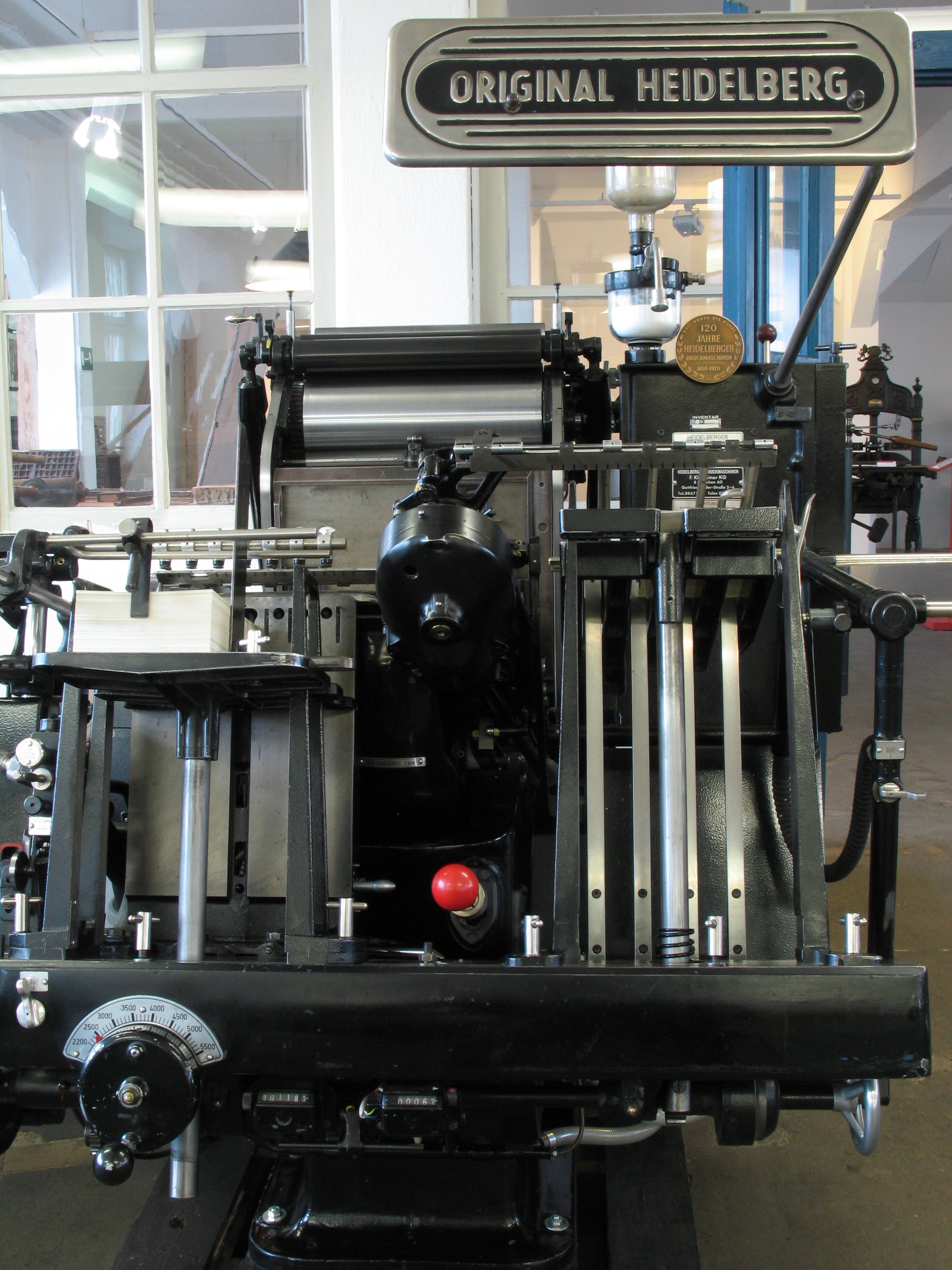

Other complex and powerful printing presses include the very common ‘Original Heidelberger Tiegel’ jobbing press or the ‘Gudrun’ (aka Victoria Front) oscillating cylinder engine. With three operators, the toggle press is able to print around 80 sheets per hour, but from 1812 onwards, the first high-speed presses made it possible to produce 800 to 1,000 sheets in the same amount of time. Later models achieve an output of 5,000 sheets an hour. The exhibited ‘Heidelberger Tiegel’ manages 5,500. This is possible because the sheets are dried during printing itself, and with certain models, the sheets are also fed and stacked automatically. Innovations are always closely intertwined with the historical situation in the given country. A significant proportion of developments in England occurred throughout the course of the Industrial Revolution. Back then, certain materials were only available in specific countries. A guided tour of the exhibition also explains that, in the past, machines were not always operated with steam alone, but with manual labour (sometimes even child labour), too.

A meaningful insight into the cultural and technological history of printing

For all their visual appeal, the exhibited machines are not revered. Indeed, the constant urge to perfect the art of printing is palpable. That is not to say that the more traditional techniques are being confined to history, however; in fact, they still possess a certain allure – not least when artists use them. In such cases, the focus is not on the demands of everyday mass production; instead, certain aspects of the historical methods are put to the benefit of the artistic approach. Another merit of the museum is that it frequently organises and runs projects to ensure that the printing techniques truly live on – in the production of posters, invitations, and flyers, for example.

Achieving speed and simplicity in typography and printing has taken longer than people often think. Indeed, a great deal of time passed between Gutenberg’s era and the arrival of the modern home printer. This is what makes the museum such an interesting place for the expert and layman alike. Although sadly rather neglected nowadays, printing technology has played a fundamental part in the last 500 years of human history. Anyone seeking a historical and technological introduction to the topic should look no further than the Leipzig Museum of the Printing Arts.