Table of Contents

Masters of comics: Jean Giraud AKA Moebius

Jean Giraud was born in Nogent-sur-Marne, a small town north of Paris, on 8 May 1938. From an early age, he loved drawing and reading American comics. It was in these formative years that he first set eyes on “Le Tours du Monde” and was blown away by their engraving, a technique that would heavily influence his style.

After attending the Ecole des Arts Appliqués, he picked up work in advertising illustration. But his true calling lay in drawing comics. And Jean Giraud was not any old comic-book artist, but a multi-faceted personality who would go on to influence science fiction and the medium of comics as we know it today.

What has always stood out about this author, apart from his natural talent for drawing and the way he puts together a page, is his versatility. Indeed, his entire career was marked by a stark duality: he wrote under two different pseudonyms, Gir and Moebius, each with a completely different style, one classical the other avant-garde.

But there is more to Jean Giraud than this. His vision contributed to and inspired other areas of popular culture, such as cinema, placing him among the most important artists of all time.

Debut and creative schizophrenia

At just 18 years old, Jean Giraud made his comics debut in Far West magazine with Les aventures de Frank et Jérémie: the style was fairly classical, with none of the extreme experimentation that would come later. After spending nine months with his mother in Mexico, where he also soaked up influences that would inform his style, he became the assistant and student of Joseph Gillain, AKA Jijé. Gillain was the much-admired author of the Jerry Spring Western series and worked with some of the biggest French and Belgian magazines, including Spirou.

Under the influence and guidance of Jijé, Jean Giraud discovered the vast world of bande dessinée. He signed his initial work Gir. But this pseudonym represented just one side of the author’s creative schizophrenia: in 1963, Giraud also began penning stories under the name Moebius for Hara-Kiri magazine, which would morph into Charlie Hebdo. The pseudonym Moebius was inspired by the mathematician August Ferdinand Möbius, who lends his name to the eponymous strip.

With Moebius, he adopted a different, more avant-garde and experimental style, initially with surreal stories, such as L’homme du XXI siècle, which was influenced by the style of American magazine MAD.

Shortly after his first stories in Hara-Kiri, Jean Giraud got a another big break: the chance to work with Jean-Michel Charlier, the great comics writer and co-founder of Pilote magazine alongside Albert Uderzo (Asterix) and René Goscinny (Lucky Luke). Charlier suggested Giraud create a series of Western comics: 31 October 1963 saw the release of the first Blueberry adventure, today considered a classic and renowned the world over. He created this piece under the name Gir.

Blueberry and Gir: classicism meets experimentation

Many consider Jean Giraud’s duality as something clear: when he worked as Gir he had a classical style in the Franco-Belgian tradition, while with Moebius he unleashed his creativity. This is partly true, but there’s much more to it. With the Blueberry series, often thought of as “cinema on paper”, Giraud worked on narrative techniques, on the clear lines typical of French comics, as well as on the realistic depiction of the environment.

Over the years, Giraud got better and better, stunning people with complex, realistic pages rich in detail. As he explained:

“For me, Gir was about learning to draw. At the beginning, I had lots of shortcomings […] Understanding space, form, harmony, lines […], took me a long time. Whereas Blueberry was a testing ground.”

Experimentation, especially with drawing and the structure of pages and anatomies, was also evident when the author worked as Gir, only the aim was to achieve realistic results. Giraud never abandoned Blueberry, which had become one of the most successful series for its publisher, Dargaud. But what was happening in the world at the time also shook up the world of comics and their creators. The protests of 1968 and their demands sowed division between the more traditional authors, such as Asterix co-creator Goscinny, and younger comics artists who wanted to create something completely new.

Revolution was in the air in the United States, too, where the Comics Code Authority still censored publications: in response, the underground comics movement began rewriting the now old-fashioned rules of the medium. A case in point was Zap Comix magazine, founded by Robert Crumb, which Giraud greatly admired. And so Giraud returned to Moebius.

Moebius and the comics revolution

The transformation began with the publication in Pilote of a seminal story, called La Déviation, which encapsulated all the changes that the author and the world around him were facing. It was still written under the name Gir, but it was immediately clear that something was afoot: using a style that resembles engraving, the technique that had so fascinated him as a child, it’s a story drawn in ink about a surreal road trip that’s almost autobiographical.

The metamorphosis into Moebius was completed in 1974 when, together with Philippe Druillet, Jean-Pierre Dionnet and Bernard Farkas, Giraud founded the Les Humanoïdes Associés group, a publisher that to this day is associated with the avant-garde and experimentation in European comics. In 1975, another outlet for this experimentation arrived in the form of Métal Hurlant magazine, which saw Moebius at his most self-aware.

Métal Hurlant contained many science fiction stories, which, metaphorically, speaks to the presence of Moebius. The first story by Moebius for this magazine was Arzach, in which the main character flies across huge and evocative landscapes on a pterodactyl. In Arzach, page after page, panel after panel, we gradually realise that there’s practically no storyline, but instead a succession of fantastical visions that push the boundaries of reality. In a legendary editorial from 1975, Giraud says that comics must defy convention and escape the rules that stifle them: “A story can be in the shape of an elephant, a field of wheat or the flame of a match”, he wrote.

The epitome of this vision is Le Garage Hermétique (The Airtight Garage): a surreal story with virtually no plot, it was published in monthly episodes. Moebius drew these stories by improvising, creating a muddled narrative as he went along that doesn’t really reach a conclusion.

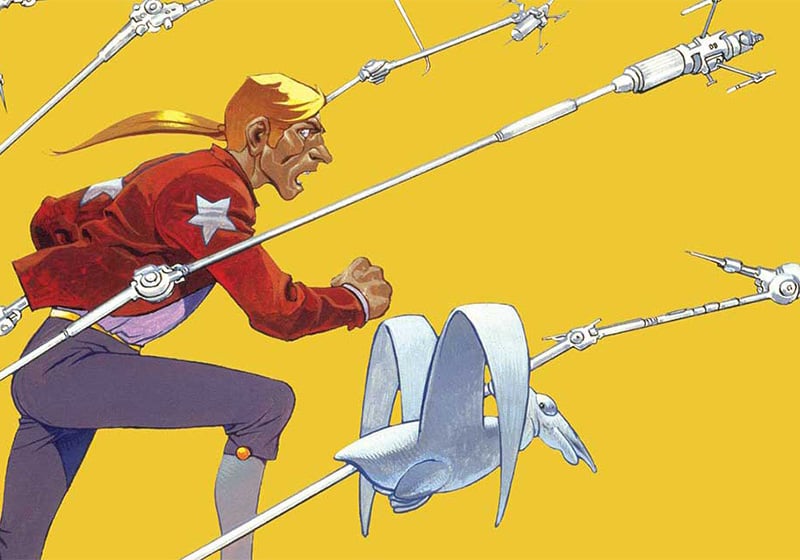

It was also in the pages of Métal Hurlant that between 1981 and 1988 Moebius published another of his masterworks, The Incal, written by Alejandro Jodorowsky, the famed Chilean film-maker. This time, the plot was more understandable: it’s a space opera set in a dystopian future with exquisite drawings and masterful use of colour.

Moebius, cinema and other work

Not only was Moebius a revolutionary master of comic-book art, but his long career also saw many excursions, even if sometimes only indirect, into the world of cinema. For example, a short story of his, The Long Tomorrow, served as visual inspiration for Ridley Scott in making Blade Runner.

Moebius also worked directly with Scott, devising the concept art for his 1979 film Alien. He also created the virtual atmosphere seen in the film Tron, as well as the monumental storyboard for Jodorowsky’s never-released film version of Dune (based on Frank Herbert’s novel).

In 1988, he also collaborated with Stan Lee and Marvel to create Parabola, a story about the Silver Surfer character. He even worked with Japanese master Jirō Taniguchi, writing the scenario for Icaro.

Jean Giraud defined the Western comic, redefined science fiction and completely revolutionised the medium, influencing generations of future comics artists. He was a genius whose work knew no boundaries and continues to be studied and admired today.