Bark from the common fig tree

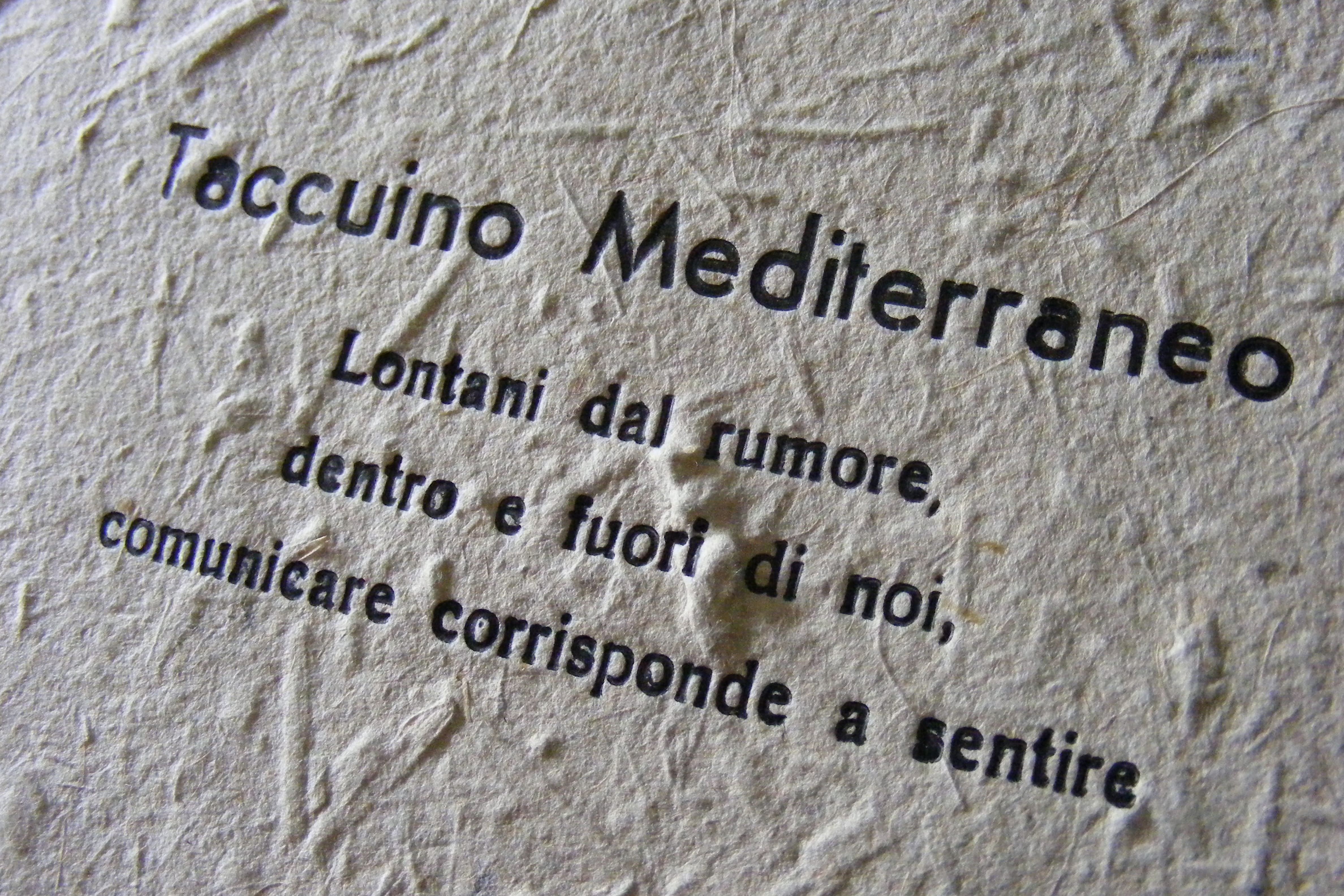

The art of Andrea De Simeis, an engraver and master papermaker from Italy’s Salento region, belongs to an ancient world where patience, thoughtfulness and attention to detail are used to express the most intimate feelings.

In his workshop in Sogliano Cavour, near Lecce, Andrea uses fine, luxurious paper made using old techniques dating to 7th century Asia and medieval Italian fullers.

Andrea, you have chosen a really unusual profession: engraver and papermaker. How have you managed to turn a passion into a career?

When I stopped working as an advertising graphic designer I had no idea that I could actually make a living from these two activities… it was a leap in the dark but it wasn’t an amateur endeavour. I realised that most industrially produced paper didn’t meet my creative needs, so I started researching how to make paper myself. The key moment came when I discovered that the fibre of Ficus carica, also known as the common fig tree and found all over Salento, had similar characteristics to Korean mulberry, the plant used to make washi, the traditional handmade Japanese paper.

In this initial phase, comparing notes with various international organisations working in paper production and intaglio printing helped me a great deal. I began to win significant recognition, including a review from Florence’s Centro di Patologia e Restauro del Libro (Book Restoration Centre), which described my paper as a faithful reproduction of washi but made with cellulose from Mediterranean plants.

What happens in the papermaking process and how long does it take you to make a batch of paper?

After gathering and steaming the bark, I strip it by hand and simmer the fibre obtained in water. Next, I put the fibre in a big pot containing ash and thyme, so that it absorbs the alkaline salts and phenol used to disinfect it. I then beat the cellulose with a mallet so that it keeps its full length and makes the paper strong.

The pulp obtained is then dispersed in water in a vat. At this stage, I sometimes add natural dye made from Mediterranean plants like the Indigofera tinctoria, which turns indigo blue upon contact with water. I use other plants from my pharmacy to add scents and flavours to the cellulose, creating a paper that gives a truly sensorial experience. Next, I strain the fibre using a screen and, after making a pile of several sheets, I squash them with a screw press to remove the water before hanging them out to dry.

In the Eastern tradition, the whole production process must take place without the paper starting to macerate, which means working within a certain temperature range and time scale. That’s why I only strip as much bark from the tree as I’m able to process. Roughly speaking, in a four-month working season I manage to produce about a hundred sheets.

How do you make your engravings?

Intaglio printing is a craft inherited from goldsmiths and armourers: in the olden days, weapons and jewellery were engraved with aqua fortis, an acid that corroded the metal leaving behind various types of decoration. It was Maso Finiguerra, the fifteenth-century Italian engraver and goldsmith, who had the idea of inking engraved metal and transferring the ink onto paper using a press. And so the mass reproduction of images was born. I inherited this ancient tradition, and I use an intaglio press for my engravings.

It seems that there’s no room for modern technology in your workshop. Is that so?

Recently, I was a guest of some Japanese artists and artisans, learning how they produce washi, and I saw the true worth of their knowledge, whose price is the compensation for their hard work. These artists would rather let certain knowledge die with them than give it over to digital sources. Our work is not just about trading and making a living; there are things that are more valuable, whose worth is the willingness to embark on a journey.

Technology is no substitute for a handicraft that must be experienced, whose expertise passes through the hands only. There is a need for digital technology, but not as much as for hands-on experience and the tangible learning of things. The very etymology of the word “aesthetics” lies in exploring the world through the senses.

Are firms interested in the creative potential of this rare material?

In Italy, we boast extraordinary craftsmanship, but there is often a lack of connection with international brands because, as artisans, we tend to lock ourselves in our ivory towers. Now more than ever, outstanding products marketed as collector’s items can be promoted by emphasising their unique handmade craftsmanship, even if “mass produced”, and orders arrive from around the world.

My clients are producers of wine, beer, and paper jewellery, as well as packaging companies and publishing houses. The latter are particularly interested in my edible books, which bring sensorial experiences to life for the reader. It’s no joke: with the right seasoning, a cellulose book can be a great meal!

How do you express your artistic personality through intaglio printing?

In intaglio printing, you work blind: there’s no immediate correlation between the process and the quality of the image, because the image is made on a matrix and printed in reverse, in other words back to front. The moment of truth comes with the press. Intaglio printing challenges the artist; it requires great knowledge and does not allow second thoughts. It’s this confidence that lets you cut the matrix with a well-thought out image, one that has been on an inner, mental journey before reaching the printing press.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m decorating a series of old pot and pan lids with Eastern patterns inspired by Iznik pottery. Also, I’ll shortly be creating woodcuts based around the theme of Totentanz, or the Dance of the Death, utilising a 14th-century technique that uses inked wooden matrices that are then pressed onto paper.