Table of Contents

Long before video games were invented, three-dimensional and interactive hand-crafted paper objects were transporting children and adults alike into magical worlds. Yes, that’s right: pop-up books!

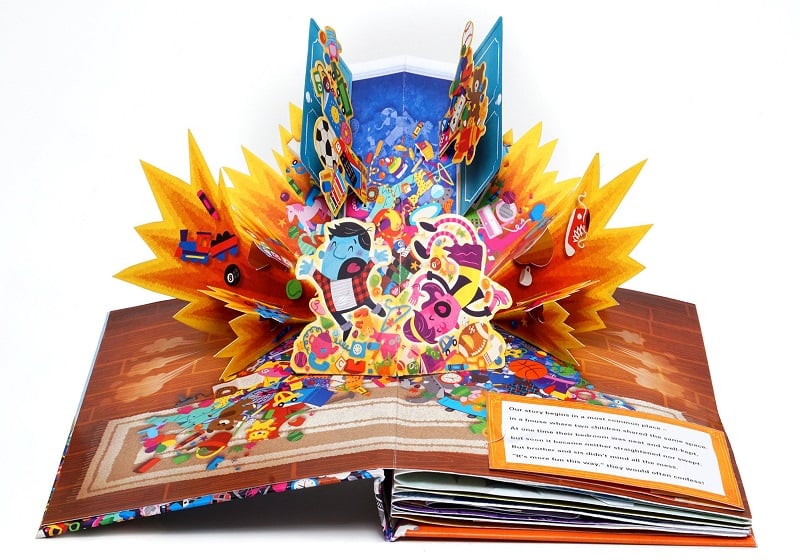

Whenever readers young or old open a page, they see the illustration come to life and become 3D: the three caravels Christopher Columbus sailed to the Americas, young Mowgli’s jungle with elephants and giraffes, or the deepest reaches of space, with astronauts that wave their arms thanks to a small paper tab.

The history of the pop-up book consists of a series of small inventions over the centuries by great visionaries who were not afraid to experiment. But how did they manage to take books beyond two dimensions.

The first movable books: medieval cosmogonies and navigational treatises

What was the first ever pop-up book? Unfortunately, the answer to this question currently evades us: retracing the origins of the ancient art of getting pages to move is not straightforward. However, there are various theories in circulation.

For example, Massimo Missiroli, a collector, creator and publisher of pop-up books, told us that a small piece of paper attached to the page with a cotton thread was found in a thirteenth-century manuscript in a French abbey [read the full interview with Massimo Missiroli on the Pixartprinting blog]. Was this the first interactive book?

We can be sure that the first movable pages appeared before the invention of printing. Various medieval manuscripts contain volvelles: movable shaped and overlapping paper discs that were attached to the pages. By turning the wheels, readers could complete complex calculations or visually explore the era’s astronomical and philosophical systems. One of the first people to use this mechanism was Raimondo Lullo, the Catalan poet, philosopher and mystic.

You have to admit, the first experiments with interactive pages were a long way from the fun pop-up books of today!

The arrival of printing: interactive maps, vistas and human bodies

Following the invention of movable type, books spread rapidly across Europe. And some of these also contained moving pages. Take, for example, the Liber Cosmographicus, a sixteenth-century bestseller by German mathematician Peter Apian. The book featured five movable and rotating mechanisms that enabled readers to interact with its paper maps and astronomical tools.

In this period, interactive inserts were also used to explore the human body, delve into the art of perspective, provide examples of architecture and explain complex astronomical and philosophical theories. It was only from the mid-eighteenth century, however, that interactive mechanisms on paper also started to be used in more frivolous ways.

A fun paper object that became very popular in this period was the harlequinade – a publication made up of single sheets folded into four, the size of a modern brochure. They oftens starred the pantomime character Harlequin and recounted his attempts to master city life or his journeys around the world. Each paper flap could be lifted to reveal the content underneath, in some cases up to three different images.

Here is an explanation of how a harlequinade works: this particular one has a precise moral aim, describing how people’s appearance hides their virtues (and vices!)

Although early harlequinades aimed to teach adults a particular lesson, the English publisher Robert Sayer soon started to produce some dedicated exclusively to children, allowing them to fantasise about stories and characters from all over the world, and revealing beautifully hand-coloured illustrations each time.

Pull-outs and pop-ups: experimenting with ways to amaze readers

From this point on, people began experimenting with new ways to make books interactive. Publishers at the time had a clear objective: to make books appealing to children and therefore boost sales.

In the nineteenth century, for example, some of the most famous adventure stories like Gulliver’s Travels and Robinson Crusoe contained pull-out illustrations, a bit like paper dolls, so readers could change the characters’ outfits as the story progressed.

Another mechanism that appeared in this period was 3D illustrations. The publisher Dean & Son was the first to use this ingenious solution, which would go on to be incredibly successful. Small ribbons were used to support highly complex and detail-rich illustrations, which could be viewed from various angles. For the first time, books could transform their images and content into something three-dimensional!

Probably the most inventive experimenter of that period was the German Lothar Meggendorfer. Meggendorfer was renowned for his extremely complex movable illustrations: apparently, for example, he managed to recreate the scene of an enormous banquet, with a single tab that moved the eyes, mouths, arms and legs of all the guests.

The invention that would come to symbolise all interactive books, however, was the pop-up book, where all you have to do is open the page and see the flat illustration become three-dimensional in front of your eyes.

The father of this invention was British illustrator S. Louis Giraud, who honed his craft in the 1940s. He and a series of books published by the London-based Strand Publications actually saved the interactive book sector from extinction: this niche market had suffered a crisis during the First World War and was struggling to recover. The name pop-up book was used for the first time a few years later by a New York publisher, Blue Ribbon Publishing.

During the twentieth century, production costs fell and pop-up books began to… erm… pop up all over the world! In Prague, for example, the Czech architect and illustrator Vojtech Kubasta produced over 100 pop-up books for Atria, the state publisher. These masterpieces have now been translated into at least 12 languages and are much sought-after by collectors and fans on the genre.

Vojtech Kubasta is famous for his illustrations that are packed full of details despite being built with very simple mechanisms – usually just a single sheet of paper. One of his best-known works is The Fleet of Christopher Columbus, which describes the discovery of America and includes an incredible pop-up illustration of the three caravels Columbus sailed to get there. But Kubasta’s pop-up books take children to myriad different places: from the Arctic to outer space, and from the jungle to the factory.

Interestingly, it was this artist’s work that kick-started pop-up book production in the USA, where interactive books had previously been few and far between. The American publicist Waldo Hunt stumbled upon one of Kubasta’s books and fell in love with it. He tried to contact the Czech publisher, but never received a reply: this was the Cold War era, and exports to the United Stated must not have been a priority for them.

So Hunt decided to found his own publishing house – Graphics International – and published dozens of pop-up volumes of his own!

I wonder what future surprises the world of pop-up books has in store?