There’s a material that is inextricably intertwined with our history like few others. A substance that takes us back through the last few centuries of Western civilization. That connects us to the water, forests and mountains of our continent. That combines culture and technology, the means for making art and the indispensable material for writing, the glamour of premium packaging and the prosaic need to wrap vegetables or carry the shopping home. The pragmatic need to label a product and the trivial desire to invite guests to a party.

It is paper, whose smell fills our nostrils when we open a new book, whose rustling brings aural pleasure to every book lover, and whose touch and feel even e-book devotees miss. It comes in all shapes, thicknesses and colours. “It’s crazy what you can do with paper,” sums up Marco Bertolo, sales director at Favini, one of Europe’s leading paper producers.

Stepping inside a paper mill is a bit like entering a temple to paper. It also gives a glimpse of the ingredients that make paper so magic and versatile. Paper production first began at this site in 1736, during the Republic of Venice. The Favini family entered the business in 1906 at Rossano Veneto, where there still stands the plant that produces one the finest papers available. “We’re paper craftsmen,” explains Bertolo. “We make special paper: we don’t have enormous machines, and we can’t do mass-produced paper. Those who do have machines that are three or four times bigger than ours, and twice as fast.”

Like all paper mills, Favini lies next to a river. Once upon a time, to make a kilogram of paper required up to 80 litres of water. The average in Europe today has fallen to 40-45 litres, which is still a lot. But Favini holds the record. “With our eco-friendly approach, we consume just 14-15 litres per kilogram of paper”. The river still runs right into the mill, just like when it was built, but these days the water used to make Favini paper comes from the mains, with only clean, micro-filtered water discharged into the river.

Before reaching the beating heart of the mill, the long machine that spreads a coloured paste of water and cellulose onto a roller, you come across a mountain of paper and cardboard in bright colours and pastel tones, strictly organised by shade: these are the offcuts, which will be reused once production of the same shade of paper starts again. Because cellulose is cellulose, and can easily be recycled if it hasn’t yet been printed with ink. Raw cellulose looks a bit like a sort of kitchen roll. Favini uses cellulose from Brazil, North America and several European countries. It can be short fibre, which is better for printing due to its good colour rendering, or long fibre, which is stronger and more suitable for shopping bags, for example.

But Favini also uses waste from food production to make paper, something which sets it apart from other manufacturers. Outside the mill are sacks of citrus pulp, chaff from almonds and maize, husks from coffee and green beans, marc and olive pomace. There’s also seaweed flour, which earned Favini a far-sighted patent in the 1990s, when algae invaded the Adriatic sea and Favini saw an opportunity to reduce the amount of cellulose required to produce its paper (see interview).

The type of cellulose used depends on the type of paper being produced. Brought in on tracks, the balls of cellulose end up in two enormous pots, called pulpers, in which a rotor smashes the cellulose and mixes it with water and the chemicals used to create the final pulp. These include talc or kaolin, minerals that fill the cracks between the cellulose fibres and help give the paper its shine, or the chemicals calcium carbonate or titanium dioxide, which play the same role; other additives include bonding agents to improve printability, as well as colours and opacifiers.

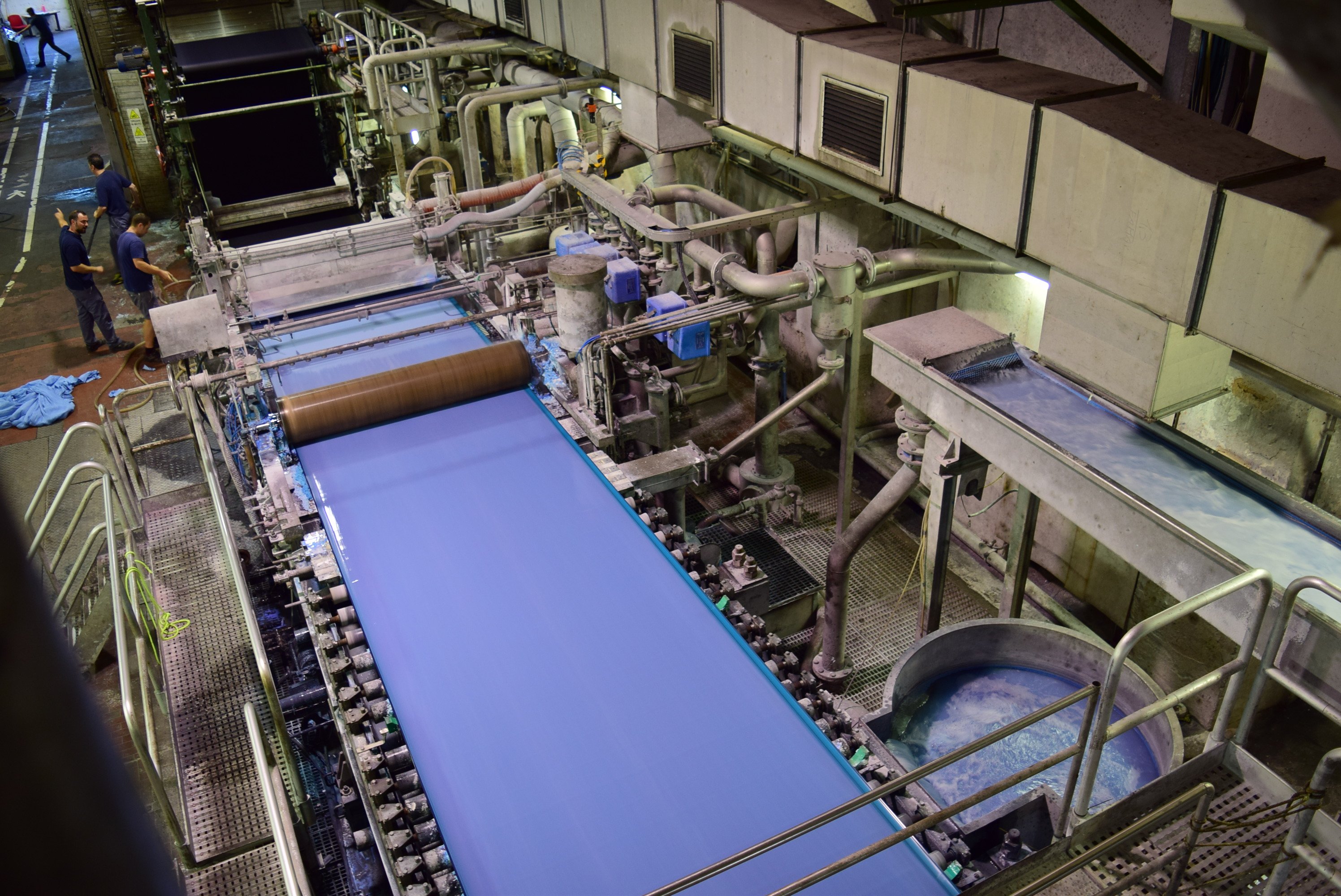

Now comes the most aesthetically (and audibly) impressive of the first moments in the life of paper. When the paste is finished, it’s put on a Fourdrinier machine. Here it’s deposited on a sort of conveyor belt. If the paper weight is low, 80-90g per square metre, less paste is deposited and the machine runs faster. Conversely, if the weight is higher, the belt runs slower to give the fibres time to stick. The paper is then dried in drying cylinders, which work like an oven to remove all moisture.

At this point, once its quality has been checked, the paper is wound into giant coloured rolls. For the most luxurious products, the paper will be embossed: in other words, it will be pressed against a metal cylinder with a design in relief that will leave a pattern stamped onto the paper, for a premium finish. After leaving the embossing machine, a series of guillotines will cut the paper to the right format.

“Unfortunately, things don’t always turn out right every time,” explains Marco Bertolo. “Some production runs don’t meet pre-determined quality targets. In such cases, we may not realise until it’s too late, when the roll or pallet have already been produced. If the paper is low- or mid-price or value, we re-pulp it, or in other words, recycle it. If, on the other hand, the paper is high-value and production reports tell us that the defect is only present every 100 or 200 metres, it would be a shame to throw everything away”. And that’s where the expert eyes of the professionals come in. Working at an impressive speed, they’re able to scrutinise sheet after sheet and pick out those with production defects, so they can be discarded. It’s painstaking work, humbly performed with love and dedication.

Once it’s passed this last quality check, Favini paper is finally ready for be delivered to its customers and to arrive in our homes and our lives. But now we know how much this paper costs to produce, we can no longer blithely say: “it’s just paper”.