Other than water and cellulose, to make paper you need a good chemist. Because that’s whose job it is to ensure that the entire technological process underlying paper production actually works, and that the paper has the required chemical and physical characteristics. Favini’s chemist, with 30 years’ industry experience, is a man called Achille Monegato. His most satisfying achievement was discovering the production method that would make the company famous: paper made from seaweed.

Achille Monegato, is a chemist with a love of Primo Levi. “The Periodic Table is the book that led me into this career after college ,” he says with bright eyes. “I’ve know everything about Levi for years,” he adds. Monegato has worked in the paper business for 30 years, ten of which were spent with a multinational abroad. The rest of the time he’s been at Favini. It was he who gifted Favini with the patent for making paper from seaweed.

What does a chemist do in a paper mill?

These days, he’s mainly a technologist, overseeing the technological aspects of paper production. The plant engineers then put it all into practice. The fundamental difference with everybody else is that the chemist has a sense of the material. For me, the end product is more important than the process itself. And we chemists have a special awareness of colours.

What difference is there between the role of an industrial chemist in Levi’s days and now?

What difference is there between the role of an industrial chemist in Levi’s days and now?

Fundamentally, my job today is the same as Levi’s in the fifties. Then Levi became a director. However, even he was focused on elements, on matter. Compared to when Levi started working in the chemical industry at the end of the forties, the difference is that then there was a shortage of raw materials, so there was less innovation. Today we have far more raw materials and special products to work with: all we have to do is find the best way to blend them.

Can you give me an example of how you apply your know-how to make paper?

We have to apply a special product to the surface of the paper to make sure that the ink binds, because otherwise it comes off. In this case, we’re trying to seal the paper with a polymer, which should create a sort of film. We have to regulate how this is absorbed. A chemist’s work is still very practical; there’s a homemade aspect to it. Artificial intelligence will arrive here too, but it will take a bit of time.

What’s the greatest professional challenge that you’ve faced in your 20 years at Favini?

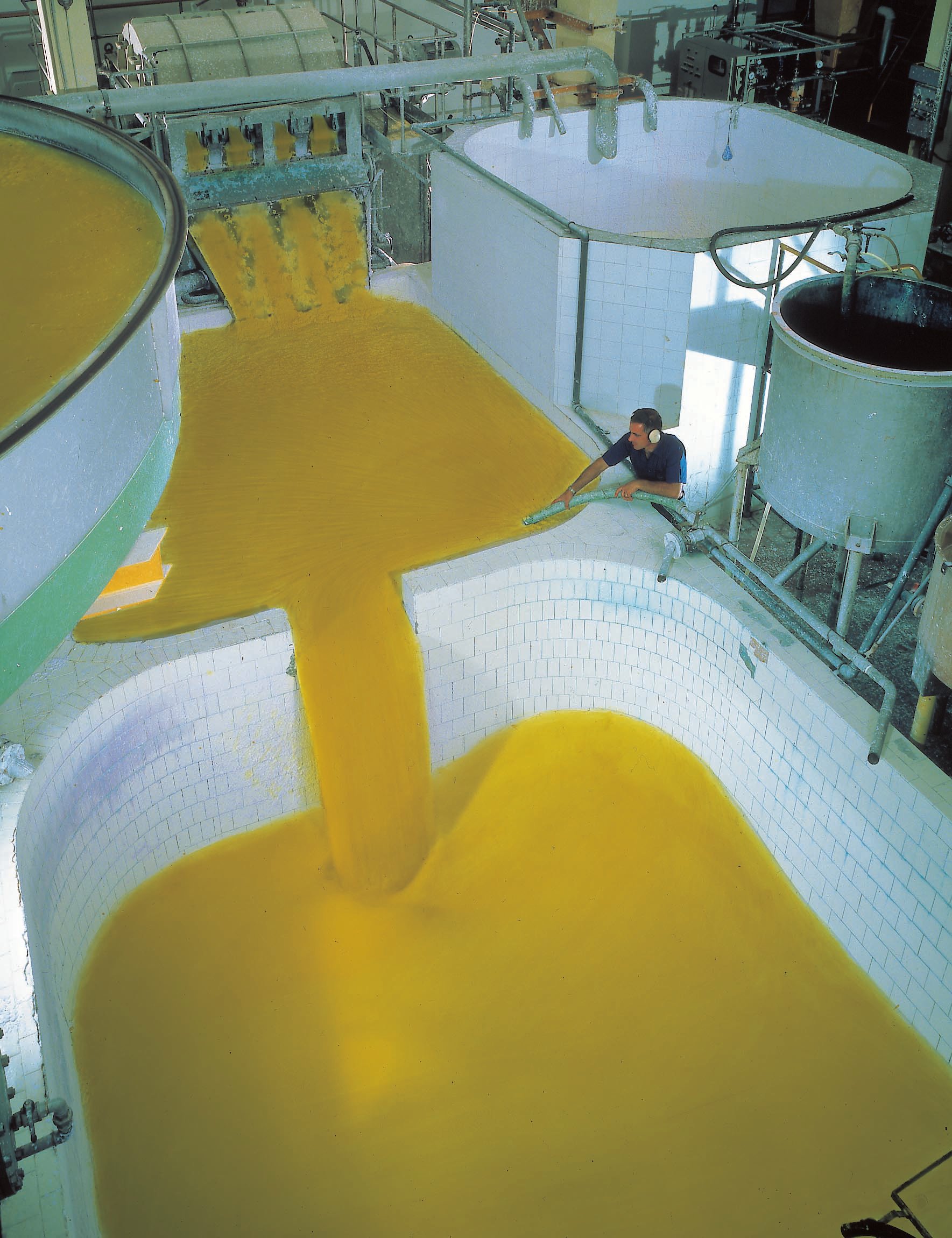

The one that brought me most fame, and greatest personal satisfaction too, was working out how to make paper from seaweed in the nineties. It’s my patent. As a chemist, I know that matter cannot be destroyed. An atom of carbon can be calcium carbonate in a mountain, or trapped in a cellulose fibre. This is the principle behind the re-use of waste and by-products to make new products. We were the first to take on the seaweed challenge and that gave us greater visibility. I took us almost two years. Initially, when we got hold of the seaweed from the Venice Lagoon, it was a bit inconsistent. I was quite young and inexperienced at the time: I tried to extract the cellulose with methods that I’d found in the literature. I even bought myself a pressure cooker because I needed an autoclave. I boiled seaweed in it with caustic soda to see the fibres. It stank terribly; I had half the plant against me. But we didn’t manage to get anything out of it. So we decided to dry it to preserve it. That’s when I had the idea to grind it and turn it into powder. The trick was finding the right dimensions. We got there somewhat by chance, and in the end we managed to optimise the technique with the right dimensions. After that, I tried with orange peel and grapes. That was in 1992. At the end of the day, the idea was simple: get it, dry it, grind it to the right dimensions and then put it in paper. That’s how we opened up a world that nobody had ever explored before.