Table of Contents

The life and work of Dino Battaglia, the influential Italian comics artist who elevated the medium to an art form.

Dino Battaglia was born in Venice in 1923. Although considered one of Italy’s greatest comics artists, he remains little known in the country, probably due to the fact that he did not come to be associated with any one character in particular. Hugo Pratt called him “the master of masters” because of his outstanding drawing technique and a distinctive style that combined narrative and visual elements in an innovative way.

Battaglia has been described as an “illustrator” by some peers, chief among them Sergio Bonelli, who thought the Venetian’s work placed too great an emphasis on drawing, at the expense of storytelling. It’s a label that Battaglia never accepted, but which nonetheless stuck to him throughout his career.

Childhood and early work

Dino Battaglia fell in love with drawing at a very young age. Although he attended a secondary school that specialised in art, Battaglia taught himself to draw comics. As a teenager, he would roam Venice, looking for monuments, alleyways and atmospheres to draw. This misty and mysterious setting would heavily influence his later work.

After the Second World War, Battaglia began illustrating children’s books for a publisher based in Florence. His confidence was growing, but his style had yet to mature.

Asso di Picche, Argentina and the fifties

Dino Battaglia’s debut proper was published in Asso di Picche magazine, for whom he drew the Junglemen series, sharing duties with Hugo Pratt. Together with the likes of Alberto Ongaro, they formed the so-called “Venice group”, a set of artists who rose to fame both at home in Italy and abroad, especially in Argentina. Pratt emigrated to Argentina in 1949, but Battaglia stayed behind and, in 1950, married Laura De Vescovi, who would later contribute to her husband’s comics as a writer and colourist.

Both Battaglia and Pratt drew for the thriving Argentine market. Battaglia used a more traditional style than Pratt, preferring the pen to the brush.

The work produced by Battaglia in the fifties had a standard structure, with the page divided up into closed – but evocative – panels. His creative flair would shine through in later work, but minimalist backdrops and elegant brushwork were hallmarks of his from the start.

In his drawings for the Capitan Caribe and Pecos Bill comics published by Mondadori, or his work for Intrepido magazine and the Daily Mirror newspaper, Battaglia’s style was still fairly rudimentary.

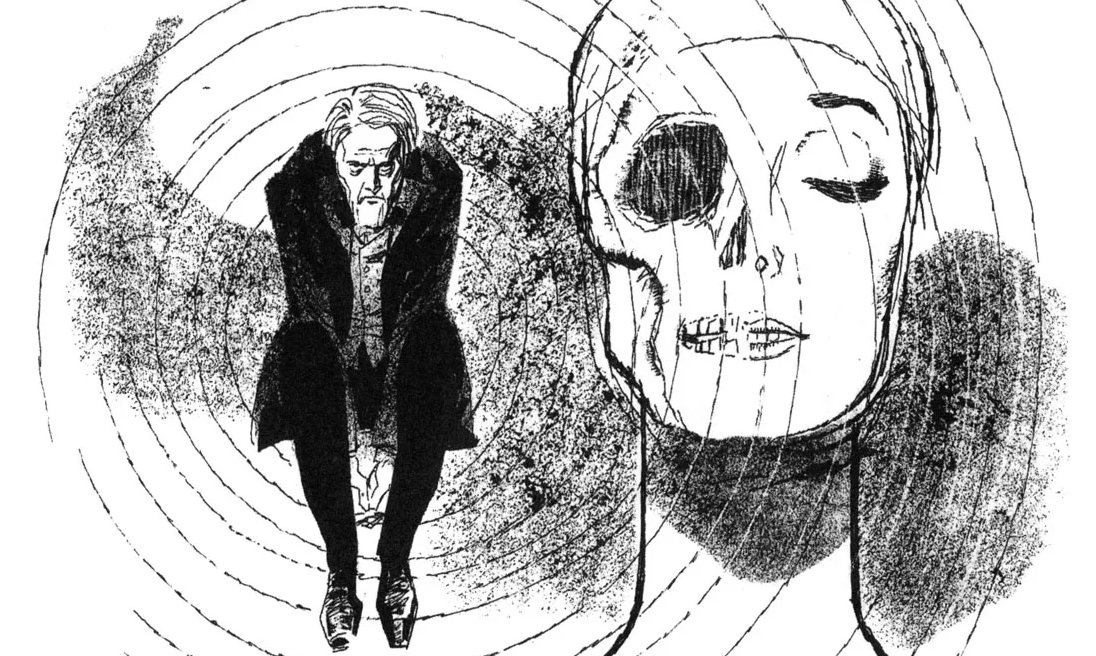

IMAGE 2

For L’Audace magazine in 1954 Battaglia illustrated adaptations of Treasure Island and Peter Pan, then from 1955 to 1956 he produced the drawings for El Kid, which was written by Gianluigi Bonelli and published by Edizioni Audace (later to become Sergio Bonelli Editore). In the same decade, he also drew for comics magazine Il Vittorioso, with standout work including The Pirate of the Mediterranean and White Piuma.

The sixties, Corriere dei Piccoli and Moby Dick

The sixties saw new collaborations with Hugo Pratt and Sergio Toppi, another great Italian comics author, for Corriere dei Piccoli. The Venetian’s best work from this period includes The Selena Five, with story by Mino Milani, and Five on Mars, which Battaglia wrote together with his wife, Laura.

Corriere dei Piccoli was a weekly children’s comics magazine with a strong educational bent. It commissioned Battaglia and others to produce a string of historical comics, as well as adaptations of classic novels, fairytales and chivalric romances. Battaglia also drew some stories for Maria Perego’s Topo Gigio.

Among Battaglia’s contributions to Corriere dei Piccoli, Ivanhoe stands out in particular for its use of elaborate sequencing in a comic aimed at kids.

A shift in Dino Battaglia’s style came in 1967 when he began adapting Herman Melville’s Moby Dick into a comic book. He pitched the project to his publisher, but was rejected on the grounds that it was “too difficult”. Battaglia continued working on it anyway. For him it was a transitional piece in which he could experiment with new techniques.

To his trusty pen, he added a new and unusual instrument: a blade, which he used to create scratchy blacks. He also employed a sponge to produce the shaded and irregular splashes of black that would become part of his signature style.

In his adaptation of Moby Dick, Battaglia showed great innovation, especially in his choice of shots and use of white space between panels to underline sudden temporal shifts. The comic book was eventually published by Ivaldi in Sgt. Kirk magazine, which was founded and edited by Hugo Pratt.

Battaglia continued contributing to Corriere dei Piccoli until 1972, while at the same time drawing for a magazine that had a more grown-up audience, one that would become the pre-eminent publication for Italian comics: Linus.

It was here that in 1968 Battaglia published The Purple Cloud, a comic-book transposition of Matthew Phipps Shiel’s novel by the same name, and then King Pest, the first in a series of adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories. In the pages of Linus, Battaglia was finally able to fully express himself creatively.

His influences ranged from expressionist cinema to Italian “black” comics and Vienna Secession paintings. Battaglia never copied, but instead took these inspirations and produced a personal blend that resulted in something completely new.

From sublime lettering, which adds atmosphere to the story, to literally exploding panels, where blacks and whites blur to set the pace of the plot, Dino Battaglia rewrote the rules of comics and innovated without ever betraying the genre. The dark and decrepit ambiance that he saw in the Venice of his youth come through in work such as 1969’s The Fall of the House of Usher, in which he makes masterful use of vertical panels to often horrifying effect.

The seventies and Homage to Lovecraft

Perhaps the epitome of Battaglia’s style is Homage to Lovecraft, published in 1970, in which the artist deftly uses white space to illustrate the passage of time and heighten the mystery in these supernatural stories.

The white space between panels grows, at times even spilling into illustrations, paradoxically creating a noir effect, which was traditionally achieved using black.

In the seventies, Battaglia contributed to the Messaggero dei Ragazzi and Il Giornalino. He then worked for Bonelli, creating the A Man, An Adventure series. At the start of the eighties, Battaglia worked with alter alter magazine, for whom he created and produced the Inspector Coke character. He wrote three stories featuring the detective: The Crimes of the Phoenix, The Mummy (which contains stunning panels produced by an artist at the height of his powers) and The Thames Monster, which was unfinished at the time of his death in 1983 at the age of just 60.

Dino Battaglia’s legacy

Dino Battaglia left behind a lasting legacy in the world of Italian comics. His influence can be seen in the work of the likes of Sergio Toppi, Lorenzo Mattotti and Corrado Roi. His stories continue to be republished and reprinted, keeping interest in his work alive.

The modernity of his style and storytelling, much admired and imitated to this day, are testament to the originality and know-how of an artist who was always ahead of his time.

Dino Battaglia showed that comics can be far more than just entertainment, elevating them to an art form for deep and complex storytelling. His skilful re-interpretation of literary classics in comic-book form demonstrated the potential of this medium, and cemented his place among the great Italian comic book artists.