Table of Contents

Before we start, fancy a Coke?

What do we mean when we talk about a digital revolution?

Let’s begin with the case of Coca Cola and Mentos. In around 2005, a couple of teenagers entertained themselves by putting a few Mentos in a bottle of Coke and filming the resulting geyser. The videos were unexpected viral hits the world over, catching the attention of the brands involved.

The marketing team at Mentos immediately understood the potential, but at Coca Cola, the use of Mentos did not go down so well: they decided to take legal action against the kids for damaging their image. But Coke would soon have a change of heart, once they saw the huge amount of interaction the videos were generating: shares, comments, parodies, copycats and more.

How bad would Coca Cola have looked in front of such a large and engaged audience? For a brand whose payoff was “Enjoy!”, telling people that the fun was over would have been seen as a betrayal of the very values of connection, interaction and enjoyment of life that Coca Cola had been espousing for decades in its advertisements.

An inversion in the communication process

Why is this episode so important?

Because it signals an evident polar inversion in the communication process. For the first time, it was brands who found themselves on the receiving end of a communication campaign, one created by people who, a few seconds beforehand, the brands’ marketing teams would have considered as their target audience. Previously, brands tended to view communication as an arrow that they fired at a given target. The audience, in this process, had a role that was pretty much passive: they could only decode the message and decide whether to accept it or not. Nothing else. On the other hand – if you think about it – before social media there were no actual physical spaces where people could build a relationship with a brand.

Previously, brands tended to view communication as an arrow that they fired at a given target. The audience, in this process, had a role that was pretty much passive: they could only decode the message and decide whether to accept it or not. Nothing else. On the other hand – if you think about it – before social media there were no actual physical spaces where people could build a relationship with a brand.

The digital era: when the target can return fire

The case of Coca Cola and Mentos marks this very change: for – almost – the first time in the history of modern communication, the target had fired an arrow at the archer. And what an arrow it was! It showed just how different the digital era was to what came before it.

Today, even the public can create communication campaigns, using a brand for their own ends or, sometimes, making them the recipient of the message. It is becoming increasingly obvious to brands that it is no longer possible to fully control the sending of messages. And often, new consumers/creators can capture the attention of the media and public as effectively, or indeed more so, than brands themselves: their content on digital channels racks up views because it is perceived in a more favourable light. It appears (but often isn’t) more genuine, authentic and innocent than content produced by brands. People like this type of content because they don’t see in it any attempt to sell or persuade. Over the years, brands have learnt to take back a certain amount of control while, at the same time, coming to accept that communication channels are no longer one-way only. Today, brands know that conversations can be started, guided, directed and managed. But there’s only one way for them to do this: by getting off their high horse and starting a serious dialogue on social media with their target audience.

It appears (but often isn’t) more genuine, authentic and innocent than content produced by brands. People like this type of content because they don’t see in it any attempt to sell or persuade. Over the years, brands have learnt to take back a certain amount of control while, at the same time, coming to accept that communication channels are no longer one-way only. Today, brands know that conversations can be started, guided, directed and managed. But there’s only one way for them to do this: by getting off their high horse and starting a serious dialogue on social media with their target audience.

But what has actually changed for communicators?

Now that we understand the context we’re in, it’s easier for us to understand the practical differences in approach this dictates. By way of concrete example, let’s take a look at the specifics of a message suitable for that quintessential digital platform: Facebook.

• Dialogue

Compared to print media, Facebook is more open and welcoming to the target audience. Interacting through comments, feedback and shares, not only do people help us understand how much they like a message, they become part of it too: their actions can and must be considered as integral to the actions of those who designed the message. Massimo Guastini, creative director at communication agency Cookies and former president of Art Director Club Italia, said: ‘The starting point for an advertising conversation is no longer what I have to say about this product, but what I can make other people say about it.’

So the takeaway here is not to receive feedback from the public passively, but to design and write a message that – as far as possible – takes into account how people will interact with it. Like in a game of chess, while you can’t predict with absolute certainty your opponent’s moves, there are many strategies you can employ to give yourself the best chance of winning.

• Conciseness

Facebook recommends (but no longer requires) an economical use of text in images for sponsored posts: the words should not take up more than 20% of the total area. So, it’s best to limit yourself to a title and visual. Obviously, this means the ability to write succinctly is vital, even more so than for print advertising.

• Metatextuality

This is perhaps the biggest change ushered in by the digital revolution, but one that is often overlooked: unlike print media, Facebook lets you add text that isn’t part of the content. You know, those bits of text that accompany an image or link to contextualise them. This possibility, which can be defined as metatextual because it allows us to provide information about how the content itself should be read, can be used in various ways:

1. To present the post.

2. To explicitly invite people to interact through a call to action. This could be, for example, by asking them a question or to express an opinion.

3. To provide contextual elements or supporting data in a way not dissimilar to how you would in the body of a traditional advertisement.

4. To highlight the post’s creativity, for instance, by inserting a joke that adds to the humour of the post itself. This can be useful for ensuring that humour is not lost if the text is read literally, generating misunderstandings that could spark controversy around the page.

5. To connect the post to a wider context of a previous page or post.

• Empathy

Lastly, we mustn’t forget that our goal is to engage, entertain and excite the people who view our content and hopefully start positive conversations about our product or service. Massimo Guastini explains: ‘An epic fail is not the only hazard for today’s copywriter: more fatal still is indifference.’ What does this mean? It means that when you speak to the public, you need to know how to reach what’s in their heart: how they feel about issues, their desires, doubts and frustrations, what makes them laugh and what generates other emotions, like anger.

What does this mean? It means that when you speak to the public, you need to know how to reach what’s in their heart: how they feel about issues, their desires, doubts and frustrations, what makes them laugh and what generates other emotions, like anger.

In other words, you need to be empathetic and create messages that are more than just product news, because otherwise they will go unnoticed and won’t get anyone talking. You need to blend information and emotion in a way that is coherent and respects the perceptions of your target audience.

Print vs. digital communication. A partnership is possible

To wrap things up, a vital fact: while in the early days of the so-called digital era we sometimes saw somewhat clumsy and awkward attempts to adapt messages created for print media – like printed pages, leaflets or flyers – to digital channels like Facebook or Twitter, today the process seems to have been flipped on its head.

Increasingly, messages originally tailored for digital platforms are proving their effectiveness in print media. When you think about it, empathy, conciseness and the ability to spark conversations are qualities that don’t just apply to communication through digital channels, but any message aimed at the public. To end things on a lighter note: remember when Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt announced their split?

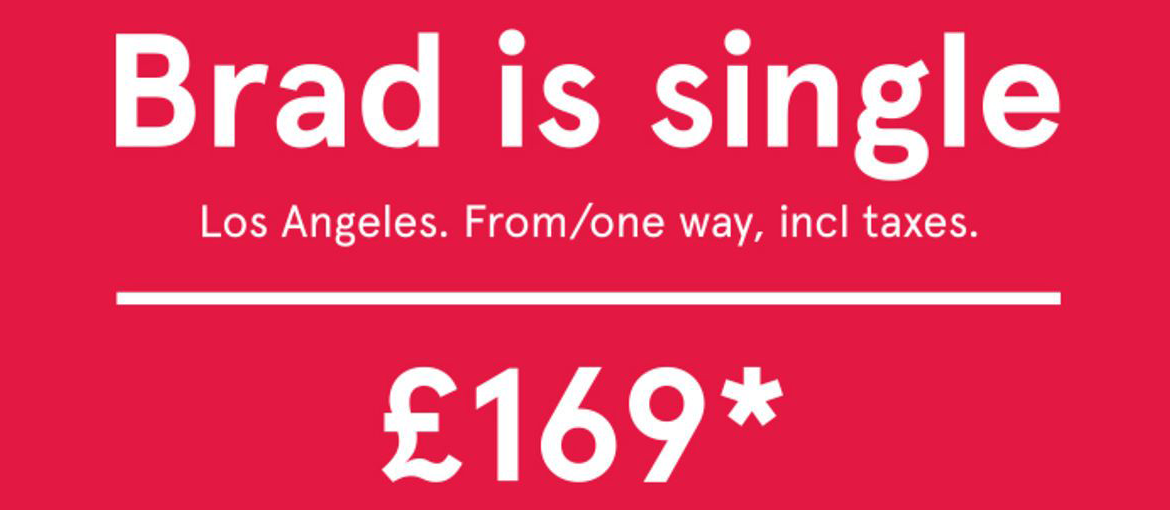

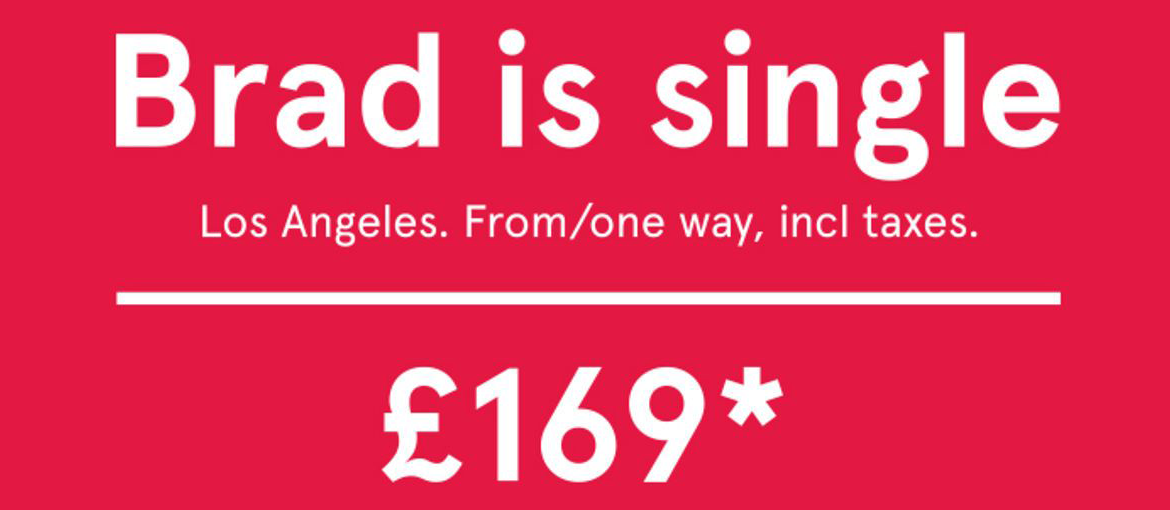

Norwegian Airlines created a message perfect for both digital and print: it featured the simple headline ‘Brad is single’, beneath which came the offer: Los Angeles. From/one way, £169 incl. taxes.

Super simple and decidedly cheap to produce, the campaign garnered attention around the world and showed that digital and analogue can intersect, if you are able to create truly relevant messages designed around the target audience.