Table of Contents

Roberto Raviola, AKA Magnus, born on 31 May 1939, is considered one of the greatest comics artists of all time, combining obsessive accuracy with a vast, high-quality output. He practically invented his own style, and succeeded in breathing new life into Italian popular comics without altering their traditional rules.

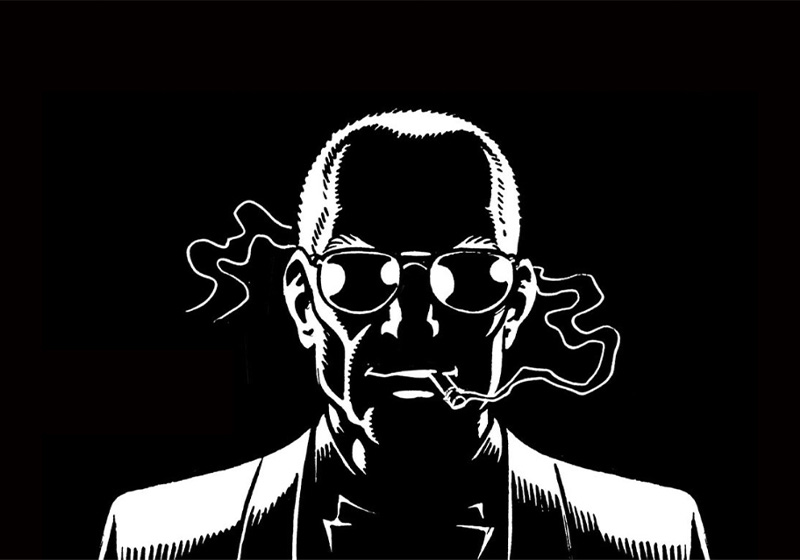

His extensive black backgrounds, the curvaceous shapes of the women he drew and his meticulous attention to detail made him a true legend, but despite this he never really managed to earn much from his work while he was alive.

His extreme dedication cemented his status as a true comics master, who has inspired countless cartoonists in the subsequent decades, particularly in the world of popular Italian comics. At his peak, he managed to deliver an incredible 600 plates a month, but over the course of his lifetime he also created some much more intimate and personal works.

Childhood, studies and influences

Roberto Raviola grew up during the Second World War, playing among the ruined buildings of a bomb-ravaged Bologna. He was always drawing, including at school: he went to a high school that specialised in the arts, where he showed a great talent for drawing and was influenced by the publications of the time: Mandrake the Magician, Flash Gordon and the magazine Il Vittorioso, which he copied diligently to improve his technique.

He signed his early comics Bob la Volpe (Bob the Fox), a name taken from a Carl Barks story, Donald Duck in Frozen Gold. After flunking his end-of-school exams, he decided to enrol at the Bologna Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied set design and decoration.

At the academy he studied under Antonio Natalini, a lecturer in historical set design who paid meticulous attention to detail. This was undoubtedly where Magnus got his bordering-on-obsessive passion for details in his comics; he would go through countless studies, sketches and test runs to get the framing or a certain expression absolutely perfect.

He graduated in 1961, and pursued further studies in decoration, before working as a teacher and a set and costume designer for various theatre performances. When working on frescos in the Buca delle Campane tavern in Bologna for the student group La Balla dell’Oca, he signed his name as ‘Magnus Pictor fecit’. From this point on, he started using the pseudonym Magnus to sign his works.

He then took a job as a graphic designer in advertising and illustrated various children’s books, but did not feel satisfied with his work. So he decided to contact several publishers in Milan, including the renowned Editoriale Corno, founded by Andrea Corno and Luciano Secchi, AKA Max Bunker.

From black comics to Alan Ford

When Magnus met Max Bunker at Editoriale Corno, Max suggested he worked on a new comic called Kriminal. This was the 1960s – the heyday of the Italian black comic, all springing from the Giussani sisters and their incredible invention: Diabolik. The huge success of this character led to a wave of anti-heroes with the letter K in their names on Italian news-stands, including Sadik and Demionak. But Kriminal was different.

Published for the first time in 1964, it starred Anthony Logan, a thief in a skin-tight yellow skeleton costume. Its storylines were rather violent and ahead of their time, and Magnus’ style, while still raw, evolved as the issues progressed: the backgrounds and figures became increasingly detailed, and his drawings were simultaneously realistic and grotesque. The page layout was similar to Diabolik: each page comprised two or three very large panels in Magnus’ unmistakable style, with large black backgrounds and razor-sharp shadows heightening the sense of drama.

As well as Kriminal, Max Bunker also worked on Satanik, a female version of the anti-hero. This femme fatale, sexually free and master of her own destiny, shattered all the era’s conventions regarding women. Magnus worked on 102 issues of Kriminal and 62 editions of Satanik between 1964 and 1971, producing an amazing 27,000 pages in just seven years.

However, the topics covered by these two comics caused a scandal, and following some legal scrapes, parts of the series were cut and the stories were toned down. Magnus decided it was time to work on something else.

Between 1968 and 1970, Raviola drew Maxmagnus, a completely different series in both drawing style and genre: written by Max Bunker and combining comic and grotesque elements, it was published in Eureka magazine, also under the Editoriale Corno umbrella. The fantasy medieval saga was based on two main characters, the evil king Maxmagnus and his greedy administrator, who bore a striking resemblance to the work’s two creators.

This series led to another contrasting publication that would go down in Italian comics history: Alan Ford, again written by Max Bunker, which launched in 1969. Inspired by spy films and James Bond in Casino Royale, it told the story of Alan Ford, an advertising graphic designer who is mistaken for a secret agent by a government agency, the T.N.T. Group. The comic started off as a social and political satire, and just a few years later it was enjoying great success.

It is still published today, with issue 660 coming out in 2024. Magnus did the drawing until issue 75, working at a frantic pace but without any dip in quality. The artist also had a major influence on the series’ scripts and gags: although the text was mostly Bunker’s work, Magnus came up with a lot of ideas during the development stages. His style kept on improving, despite always being constrained to one page of two large panels.

However, in 1973, the partnership ended: Magnus stopped working on Alan Ford and decided to pursue an artistic career less constrained by commercial success, to break free of the monotony and repetition his work involved.

Erotic comics and Lo Sconosciuto

In 1974, Magnus began working with the publisher Edifumetto, which specialised in spotting the latest trends in popular comics and creating sure-fire successes on the back of them. The top genres at the time were horror and erotica, and Magnus did not shy away from either, producing works including Mezzanotte di morte (Midnight of Death) and Quella sera al collegio femminile (That Night at the Girls’ College).

It was during this period that he decided to create probably his best-known work: the first of six issues of Lo Sconosciuto (The Unknown) was released in 1975.

The idea came to Magnus when he met a European adventurer on a trip to Tangier. He took inspiration from this encounter for the comic’s lead character, as well as drawing on influences from the era’s cinema. The first stories were edited by Renato Barbieri at Edifumetto and the singer-songwriter Francesco Guccini, with whom he wrote the volume Poche ore all’alba (A Few Hours at Dawn).

Lo Sconosciuto stars a former mercenary called ‘Unknow’ (intentionally misspelled). We know little about his past, apart from a few heinous crimes he has committed: he was in the Foreign Legion and hired for various jobs that took him to Lebanon, Haiti, Italy and Morocco.

Magnus employed a highly realistic style for this series, with a much more grown-up and sophisticated narrative than his Alan Ford days. It was a key period in Magnus’ production: as well as his pen name, he also added the hexagram I Ching, meaning ‘the wayfarer’, to each page.

Unknow is a much darker character, a lone wolf marked by his past and acting within a page layout that was finally freed from the restrictions of popular comics. This allowed Magnus to express all his drawing talent, with an obsessive attention to detail and complex scripts. In the story Una partita impegnativa (A Challenging Match), for example, he takes an almost journalistic approach to describing drug trafficking.

The series reached its apex with the story La Fata dell’Improvviso Risveglio (The Sudden Awakening Fairy), published in Orient Express in 1983, which depicts a surgical operation that saves Unknow’s life, including minute, ultra-descriptive details of the whole procedure, some of which are extremely gory.

During that period, other artists were tending to abandon complexity in favour of an elegant, clear style, like Manara‘s Il gioco, but Magnus did the opposite, adopting a more complex narrative style, less easily grasped by the general public, but much more profound. Lo Sconosciuto describes the dark side of the human spirit, and the characters’ movements and expressions, the author’s unmistakeable inking style and the stories’ palpable emotions and atmospheres gave a fresh lease of life to Italian comics.

After completing various comics for Edifumetto, Necron came out in 1981, drawn by Magnus and written by Mirka Martini (pen name Ilaria Volpe). This adult comic went beyond erotica, telling the story of Necron, a humanoid made from fragments of corpses and his lover, the mad scientist Frieda Boher.

This introduction is enough to give you an idea of the tone of the work, which only lasted 14 issues: here Magnus employed an even cleaner style, defined as ‘electronecroplastic’ – a grotesque version of the Franco-belgian ‘clean line’ style, with various grotesque deformations added to otherwise elegant pen strokes.

In the years that followed, Magnus returned to humour with La Compagnia della Forca (The Company of the Gallows), and to Eastern culture and science fiction with Milady 3000, I Briganti (The Brigands) and Le 110 pillole (The 110 Pills), a highly erotic comic with an almost flawless drawing style.

The author’s obsession with detail in his panels reached its apex with Le femmine incantate (The Enchanted Girls), a work of unmatched beauty, where each panel and area of hatching stemmed from constant study and multiple alterations.

Magnus and ‘Big Tex’

One of Magnus’s best-known works is undoubtedly Tex, or ‘Texone’ (Big Tex), as it is often known. Following various attempts to define a new style and some increasingly personal works, the artist dedicated a good seven years of his life to Italy’s most important and iconic popular comics character. This was 1988, and it came during a period of great change for the cartoonist, who divorced his wife, left Bologna and sought refuge in the mountains.

Sergio Bonelli contacted Magnus and asked him to get involved in a new project related toTex, this time with a large print size (instead of the classic Italian-style bonellide format) and including cartoonists from around the world.

Magnus worked on La valle del terrore (The Valley of Terror), with texts written by Claudio Nizzi. This comic is now universally considered to be one of his masterpieces; Magnus’s Tex was completely different from all the other Bonelli comics. He threw himself into the project, choosing to draw inspiration from the sketches made by Tex’s creator and original cartoonist, Aurelio Galeppini.

This meant abandoning the solid black areas that had been a major fixture of his work for a long time, from his dark comics period through to Lo Sconosciuto. Instead he constructed pages and panels with intricate hatching and sculptural, evocative human characters, combined with historical research and an attention to detail that went beyond obsessive. Bonelli had always published popular comics, churning out publications for news-stands every month. But Magnus refused to comply with this system, and laboured away on the project. The artist studied and sketched each period object and every leaf, stone, horse and background with the meticulousness of a craftsman, in stark contrast to the assembly line approach of popular Italian comics.

Sadly, Magnus did not live to see his work published: he died of cancer in 1996 at the age of 57. He was not a wealthy man, but he left behind a masterpiece that had dominated the last few years of his life.

Magnus’ legacy

Magnus left an immeasurable legacy for the comics world. He was a unique artist who successfully mixed graphic realism with the grotesque, and eroticism with an obsessive attention to detail. He revolutionised comics through an innovative blend of elements taken from art, literature and cinema. Even after his death, people still study and admire the distinctive style and thematic depth of Magnus’ work. He has influenced later generations of cartoonists, who see him as a model for how comics art can explore complex human and social issues with sensitivity and intelligence.

His stories – often intertwined with adult themes and existential challenges – helped to elevate comics to a recognised and respected art form, proving that they can be as provocative and meaningful as any other form of creative expression.