Table of Contents

Four-colour printing is a technique that allows an image to be printed in colour: it is currently the standard system for offset and digital printing and, as such, the most widely used in the world. It’s known as four-colour printing because it’s based on four colours, the so-called CMYK colours as we’ll see shortly: cyan, magenta, yellow and black. These colours can reproduce on paper almost 70% of the colours visible to the human eye!

That’s right, today we want to explain how four-colour printing works and the significance of the CMYK colour model! And we’re going to do so as simply as possible… which is why we’re going to answer some frequently asked questions. For example: why are only these four colours used? How are they mixed? And why is it so difficult to recreate in print what we see on screen?

Happy reading!

How does four color printing work?

As we’ve already seen, four-colour printing mixes four colours together: cyan, magenta, yellow and key (black). This gives us the famous CMYK acronym.

These four base colours making up the CMYK colour model are mixed together and, through subtractive synthesis, they create many other colours (the entire range of colours created by a colour model is called a gamut).

What does subtractive synthesis mean? The base colours printed on a white sheet act as a filter. Light passes through the first colour (magenta, for example) and the ink absorbs some of it. The remaining light passes through the second colour (cyan, for example) and more of it is absorbed. The remaining light is then reflected by the white sheet and hits our eye: that’s the stimulus for the colour we see.

How are the CMYK colours mixed?

You may think that in four-colour printing colours are mixed like a painter mixes paints. Actually, this isn’t the case.

The mixing of colours involves printing lots of tiny single-colour dots, one next to the other, using special grids called halftone screens (read our explainer on halftone screens). So a printing press doesn’t actually directly mix the colours, rather it prints dots of cyan, magenta, yellow or black colour in a predetermined size and frequency: our eyes and brains then process this information to reproduce colour!

The CMYK colours: why only four?

Another common question about four-colour printing is this: why were these four colours chosen? And why only these? As is so often the case in the history of technology, it’s a matter of affordability! Printing with CMYK allows you to achieve the widest spectrum of printable colours with the fewest base colours.

Of course, you can print using more colours: there are, in fact, printing machines that can print in six or eight colours. These are used to increase the spectrum reproduced or to enhance the brightness or realism of colours.

Companies like the legendary Pantone create so-called spot colours: specially created colours that can’t be used in four-colour printing. In its catalogue, Pantone has 1114 colours made from mixing 13 different pigments (plus black).

However, it goes without saying that printing in Pantone colours is very expensive compared to four-colour printing: printers have to specifically order these spot colours and keep them in stock!

But the most commonly used and affordable method remains four-colour printing.

The difference between CMYK and RGB

Why is it so hard to recreate the colours that we see on our computer screen? This is a problem often faced by designers, clients and amateurs alike! Now that we’ve seen how four-colour printing works, let’s try to answer this question.

As previously explained, four-colour printing uses a model with four colours: CMYK. But the colours that are displayed on our computer screens are created using a different model – one with three colours – called RGB, which stands for red, green and blue. That’s the difference between on-screen colours and printed colours!

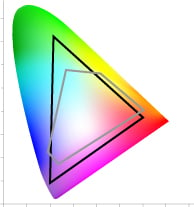

The image below shows the entire spectrum of colours visible to the human eye. The black triangle marks the colours that can be reproduced with the RGB colour model. And the grey polygon illustrates the colours that can be produced by four-colour CMYK printing.

Technically, it’s impossible to print all the colours that we see on screen. Just like it’s impossible to reproduce on screen all the colours that we see in the world around us.

What’s more, there are other variables in the equation: the type of ink, the choice of paper, the press used and a host of other parameters that printers can play with. There are of course solutions that allow better colour rendering in print than on screen, but it’s a subject that deserves its very own post… so watch this space!