Table of Contents

The life and work of ‘The Duck Man’ Carl Barks, one of the most celebrated Disney artists who created Scrooge McDuck and countless other Duckburg characters.

Carl Barks, born in 1901 in Merrill, Oregon, USA, was a key figure in the world of global comics, and one of the great masters of the ‘ninth art’. He is best known for his work on Disney animations and comics and for coming up with Duckburg, the imaginary city home to Walt Disney’s creation Donald Duck. Barks created a vast array of iconic characters, including Scrooge McDuck, Gyro Gearloose, the Beagle Boys, Gladstone Gander and Grandma Duck to name but a few. Many readers identify with these characters, which are more real and credible than those in many other ‘funny animal’ comics.

Carl Barks grew up in an era of great technological and cultural change, and succeeded in turning comic strips and books into a sophisticated medium that offered both entertainment and profound reflections on human nature and society. His over 660 stories of ducks and their adventures always paired high-quality drawings with an innate talent for storytelling, and his intricate narratives and unmistakeable illustration style helped to elevate comics to an art form, leaving an indelible mark on the medium’s history.

Childhood and early work

Barks lived a rather isolated life with his farmer parents: he had to walk about 2 miles to school every day, and he helped his parents on the farm in his spare time from a young age. As he grew up, he started to develop fairly serious hearing problems, which exacerbated his feeling of isolation, and he chose to take refuge in drawing and reading.

Barks was heavily influenced by artists like Winsor McCay (famous for his seminal work Little Nemo) and later Frederick Burr Opper, Roy Crane, Norman Rockwell, Alex Raymond and E.C. Segar. He was almost entirely self-taught: the only instruction he received was a correspondence drawing course – a very popular form of learning at the time – but his farm work commitments meant he had to give it up.

In 1918, at the age of 17, Carl tried unsuccessfully to start a career as an illustrator in San Francisco, before returning to Oregon to try his hand at various jobs. These experiences provided inspiration for future Donald Duck stories, and reinforced his belief in the power of perseverance, a quality he would later instil in his most iconic character, Scrooge McDuck.

He got married in 1921, and in 1923 finally managed to get some of his drawings published in the magazines Judge and The Calgary Eye-Opener. He had two daughters in the first few years of his marriage, but split with his first wife not long afterwards, in 1929. However, he continued his work with The Calgary Eye-Opener until 1935, when he responded to a Disney recruitment ad he saw in a newspaper.

The first few years at Disney

Barks moved to Los Angeles in 1935 and began working at Disney as an inbetweener, the person in the animation industry responsible (at the time, at least) for creating a serious of frames called inbetweens or tweens between the start and end ‘key frames’. He arrived just when the studio was launching one of its biggest stars: Donald Duck, along with his nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie.

These were complex characters who cried, got angry and experienced frequent mood swings, and this was particularly true of Donald, who had a very short temper and was often thwarted from realising his ambitions in his stories. While he was working as an inbetweener, Barks proposed ideas and gags for the Donald Duck cartoons, and showed great talent for devising comic situations with a hint of satire. This led to him being transferred to Disney’s story-writing department in 1937. Walt Disney himself gave Barks a $50 bonus for coming up with a particularly funny scene for the cartoon Modern Inventions, where a robot shaves Donald Duck’s backside, thinking it is his head.

Barks continued to write sequences for the Donald Duck cartoons, working with various secondary characters that he would later use in his comics. In 1937, the screenwriter Ted Osborne and artist Al Taliaferro introduced Donald’s nephews, Huey, Louie and Dewey in the cartoon Donald’s Nephews, which was credited to the two of them. However, a few decades later, Don Rosa, another great Disney artist who followed in Barks’ footsteps, revealed that Barks has claimed that he was the true creator of the three nephews. Officially, however, Osborne and Taliaferro still retain authorship for them.

Barks also invented Daisy Duck – initially called Donna – for a 1937 animated short. The artist was taught how to write screenplays by Harry Reeves and Walt Disney, and his first true comic for Disney was Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold (1942), written in partnership with Jack Hannah.

However, the artist stopped working with Disney that very same year – the Second World War was raging, and the studio was forcing writers to produce propaganda stories and cartoons. Barks had no interest in this and so he left Disney, blaming bad sinusitis caused by the offices’ air conditioning (Disney was a very early adopter of air-conditioning systems).

The evolution of Donald Duck and invention of Scrooge McDuck

Aged 40, Barks moved to southern California, where he planned to start a chicken farm with his second wife. Fate, however, had other ideas: Barks was contacted by Western Publishing, a publisher releasing comics under licence from Disney, asking him to create more Donald Duck stories, to try and replicate his previous success.

And so, between 1943 and 1966, Carl Barks wrote hundreds of stories starring Donald Duck, turning the previously angry and superficial cartoon character into a much more nuanced figure. Donald retained some of his impulsive and aggressive nature, but Barks also imbued him with an array of deeper emotions. His stories ranged from short gags to more complex narrative adventures, with a lead character who displayed sensitivity, patience, uncertainty, sympathy, fear, depression and even flashes of brilliance, just like a real person.

IMMAGINE-6

Donald Duck’s constant mishaps were still designed to make people laugh, but Barks now painted him as more of a loveable loser. Sometimes he was the cause of his own misfortunes, but often he fell victim to unexpected circumstances or to villains who deliberately threw spanners in the works. These emotional contrasts touched many readers’ hearts, and they particularly empathised with his constant financial struggles and his fight to keep a steady job.

The author also made the bond between Donald and his three adopted nephews Huey, Louie and Dewey much stronger and more realistic. Although they retained a certain element of their original mischievous nature, they turned out to be smart and cunning, often wiser than their uncle and eager to help him solve complex mysteries or to extricate him from tricky situations.

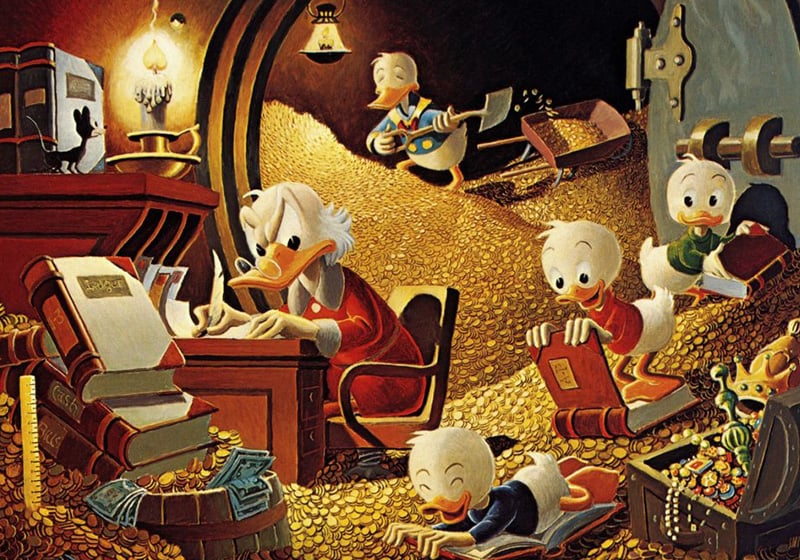

During his early years with Western Publishing, in 1947, Barks also created perhaps his best-known character: Scrooge McDuck, who appeared for the first time in the story Christmas on Bear Mountain. The artist took inspiration from Ebenezer Scrooge from Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol for this now-iconic character. Scrooge McDuck is a multimillionaire who acquired his fortune during the 1896 Klondike Gold Rush and keeps his hoard in a giant building called ‘The Money Bin’, where he can literally swim among his piles of lucre. Uncle Scrooge is also famously extremely thrifty, to the extent that even spending a single coin causes him immense upset. The character was so successful, he was given his own series starting in 1952.

Scrooge’s stories are often grounded in adventure, and are based on searching for potentially valuable rare artefacts and mysterious objects. One of Barks’ best Scrooge McDuck stories has to be the 1954 Tralla La, where the lead character leaves business behind due to the stress caused by a mysterious ‘money allergy’. Instead, Scrooge decides to go to the Himalayas in search of a lost city where money does not exist, accompanied on his quest, as ever, by Donald and Huey, Louie and Dewey, who are ‘paid 30 cents an hour’ (the allergy has not affected his stinginess).

This story offers a strong critique of capitalism and colonialism, and shows how introducing even the simplest of objects (in this case a bottle cap) can corrupt a previously peaceful and moneyless society.

Over the course of his career, Barks also created many villains to oppose the various heroes, including the sorceress Magica De Spell, Flintheart Glomgold (famous for the Duck Tales animated series) and John D. Rockerduck, another hugely wealthy character and Scrooge McDuck’s second true nemesis.

Carl Barks’ style, satire and cultural impact

Carl Barks legendary status as a comic book author stems from the high-quality storylines in his works and the way they appeal to both adults and children. He was a master at devising epic adventures full of emotions, suspense and mystery, taking Donald Duck and his family on exotic treasure hunts to ancient civilisations, mythical worlds and far-off planets. He worked obsessively on the settings: in a pre-internet age, Barks often had to rely on photographs and National Geographic magazine articles, dedicating countless hours to researching every new story.

The result was a high level of realism, in spite of the cartoon context: the artist imagined his characters as human beings, rather than simply depicting them as anthropomorphic animals. This approach allowed him to explore deep topics like poverty, misfortune and perseverance, reflecting his own life experiences in his characters, and particularly Donald and Scrooge. While his stories were undoubtedly entertaining, they also imparted important life lessons on the importance of friendship, family and hard work and showed the limits of materialism, without ever appearing rhetorical or utopian. His narrative also contained significant moral depth, often tinged with a hint of cynicism rarely seen in Disney: his ‘heroes’ could have defects and his ‘villains’ could have redeeming features.

Barks often used satire in his stories to criticise and reflect on various social and economic issues. In A Financial Fable, for instance, he warns about the perils of easy money, showing how suddenly acquiring wealth can lead to laziness, and how Scrooge McDuck’s business nous helps him speedily recover his fortune. As well as making young readers laugh, these stories also encourage them to reflect critically on the topic, preparing them to deal with the complexity of the real world.

The global spread of Disney comics ensured Carl Barks’ works had a huge cultural impact. His comics have been read by millions of people, and left a significant mark on modern culture, including influencing cinema and television. For example, the 1954 story The Seven Cities of Cibola inspired the opening scene of the Indiana Jones film Raiders of the Lost Ark, created by George Lucas and Steven Spielberg in 1981. And Matt Groening’s animated series The Simpsons has numerous parallels with Barks’ narrative world, like the structure of a community full of characters in a city with countless rivalries and local histories.

Carl Barks’ legacy

Carl Barks’ extraordinary storytelling ability, distinctive style and the depth of the topics he covered in his works left an unparalleled and indelible legacy on the comics world.

His ability to combine humour, adventure and reflection made his stories timeless and loved all over the world by generations of readers.

Barks lived long enough to enjoy the appreciation of his millions of fans, escaping the anonymity that has often plagued Disney artists since the 1960s. A year before he died, he told university professor Donald Ault: “I have no apprehension, no fear of death. I do not believe in an afterlife. […] I think of death as total peace. You’re beyond the clutches of all those who would crush you”.

He died in August 2000, aged 99, at his home in Oregon.