Table of Contents

Brian Heppell has been working in the world of lettering for over 60 years – but how can we call it working, when he himself refers to it as a “paid hobby”. Just recently retired, Brian is staying busy and is still heavily involved in calligraphy, signwriting and he does a guided walk around the sites of the historic type foundries in the City of London.

Brian, and now with his son Tim, have been running the signage design and creation studio Glyphics since 1985. In 2010 the idea of a vintage lettering shop came about as well.

I had the amazing chance to talk to Brian about his fascinating life and career, typesetting in the 50s, the meaning of true camaraderie and why change is good!

When and how did you discover your love for type and letters?

One of my school-friends had a father who worked at ‘The Times’ newspaper in London and his Dad had lined him up for a job there. My friend asked his Dad if he could get me a job there too and – to my surprise – I was given an interview and offered a job and later on an apprenticeship to become a hot metal typesetter or compositor.

I was trained by The Times in-house and also trained to be a Monotype keyboard operator later at The Monotype School in Cursitor Street, London, just off Fleet Street – ‘the street of ink’ as it was called because most of the national newspapers had their headquarters there.

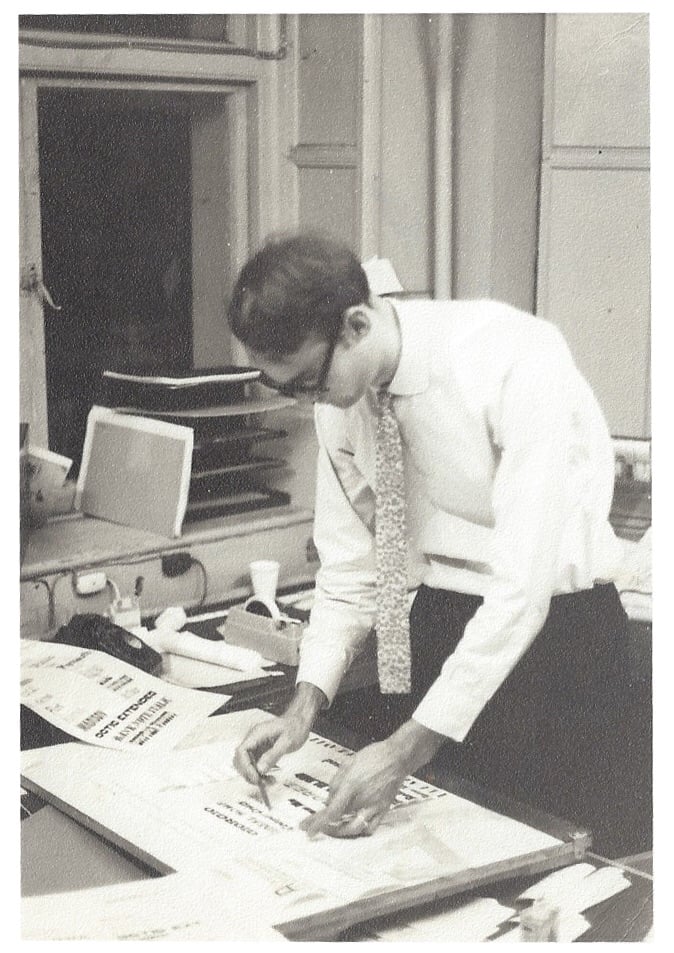

My first foray into lettering as a business started in 1964-5 when a fellow student at the London School of Printing had remembered my handwriting. He was working for a photographic typesetting company called Photoscript and they wanted someone to produce a typeface catalogue for them. So he called me up.

I came across a stumbling block fairly quickly with my catalogue design project. That’s because Photoscript was so busy doing typesetting for their customers that they had no time to set the type for their own catalogues. So I had to learn to do the phototypesetting myself.

Then I found nobody had time to complete the layout and artworking process either. So I learned to do that myself too. With the result that I eventually ended up running the Photoscript production team. I thought: “I could be doing this for myself in my own business”. That’s when I first went it alone in 1968 and set up my own phototypesetting company called Alphabet.

But soon, things were changing. Computers were coming in by this time and the resolution of the type and images produced by them meant that the demand for headline work from external typesetters diminished dramatically. Advertising agencies and design companies began to do their own typesetting in-house. That’s when I left my old partners and turned to a new career in creative lettering of another form by setting up a new company called Glyphics producing signage.

At the heart of Glyphics was my life’s experience in lettering. I knew about type design, typography, character spacing, line spacing and the way that type sits best on a page. I applied all this to a new medium – self-adhesive vinyl lettering for signage. That’s a familiar technology for most people now but back then in the late 1970s-80s, it was an innovation. And we have continued on that course to the present day.

Could you tell me a little bit about the history of the Vintage Letter shop you run?

The idea for creating a vintage lettering shop started in a conversation I had with my designer work pal, Paul Crome, and my son Tim Heppell in the studio at Glyphics about 8 years ago.

We three were all fascinated by the history of signage and were convinced that other designers, potential customers and members of the general public would be too. And we thought that by creating a shop that sourced, displayed and sold vintage letters from old shop and pub facades and general advertising, it would attract like-minded people. I took responsibility for running the shop and for searching for and buying stock.

We scoured auction sites, street markets, and junk shops, both in the UK and abroad. The Letter Shop’s fame spread as we used the Glyphics website as well as social media platforms like Instagram to display the letters we had recently discovered and the stories behind them. We sold letters only face to face, rather than online, and we welcomed customers from all over the world and groups of art students from design schools from Australia, Greece, and Japan.

Businesses also approached us for lettering displays for their offices, shops, and restaurants. We were a venue for photo shoots. I loved it and all the people that I met…and I like to think that we made quite an impact by developing the market for Glyphics’ signage services.

Did you have a network of artists you collaborate with for things like hand painting?

We have always had a network of experts we can call on both to help us with graphic design and sign painting projects. Look at the really successful design teams. They are successful because of the variety of talent that they employ or can call on. Not everyone can be a Pentagram or a graphic designer like Alan Fletcher or Bob Gill with their innate ability to find solutions to a design problem.

So it is with us. The skill of signwriting is in the individuality of that man or that woman who produces the work. So when we are commissioned to undertake a new hand painting project, we can match it to the person who has exactly the right skills for the task and who we know will be on the same wavelength as the customer and will understand their needs or aims.

It’s an interesting thing, every signwriter has a unique ‘fingerprint’. He or she may be painting, say traditional Trajan lettering, but there will be little individual touches within their work that other signwriting professionals will recognise as theirs.

The beauty of it is that you know that it has been hand-painted and not generated on a computer and cut in vinyl, perfect and uniform but without personality.

You have been in the typography and production industry for many years and you have seen massive industry changes. What do you miss from older days, what is better now?

To be honest printing and typesetting at the time I started work was a dirty, labourious job. It was heavy and hot work, lifting and carrying formes of type, bending over the bed of a printing machine all day, correcting or repairing ‘battered’ type and then cleaning the type of all its ink before it went into a bin for smelting down and recasting. All this was a process that hadn’t changed for centuries. Even the old printing pioneers like Gutenberg would have felt fairly at home on the presses at ‘The Times’ and other big newspaper and printing companies in the mid-20th century!

The arrival of the computer has obviously changed all that. Print production is no longer an industrial process. Nowadays journalists and writers virtually do all their own typesetting, typography and page design at a desk in sleek, air-conditioned offices, sometimes even at home. The printing presses themselves are generally automated. And if the newspaper or magazine is going to be distributed online, it can go live in seconds with just a touch from a single writer or editor.

This new digitized print production world has clear advantages. It is clean. It is fast. It is no doubt far healthier! But there are things I miss. The buzz of the composing room, for example, with the unique combined smell of the ink, the white spirit, the paper, and the board. But above all, I miss the comradeship: a team of people working together side by side, each with an essential part to play in crafting a fine finished tangible product. A compositor’s job was skilful. We were known as ‘the gentlemen of the press’. Quite right!

My impression of print production today is that many people are working in isolation, each at their own screen, sometimes a good distance apart at remote locations. So there’s no longer quite the same camaraderie that we used to have with our mates.

You were very open to new technologies from the beginning on – how come you are so open to new things, has this helped you in the business?

I just love progress. I love it in all fields not just in printing. I’m fascinated by advances in everything from medicine and genetics to the ways people communicate with each other. Unfortunately, I see that very often these days we also don’t use our brains as much as we used to. And we also don’t talk easily to our fellow human beings as much as we used to except via technology. I believe it’s vital to talk to people and work with people face to face as well as via a keypad or handset.

What do you think made high-quality analogue products become popular again these days?

I feel that this trend is a rebellion against the perfection of the computer-generated, mass-produced world where things are too uniform and lack any individuality. People now delight in craft skills – things created by hand by artisans, be it foods, clothes, furniture or greetings cards. They want to preserve and pursue those old skills and old technologies before they are lost forever. They embrace the idea of recycling. They like getting hands-on and creating things themselves. They appreciate the human touch. And they now recognise that you can live happily with the two combined together – hand-crafted objects on the one hand and machine-age objects on the other.