Table of Contents

Whenever the appearance of a piece of technology – a phone, for example – influences our choice of what we buy, it is down to Braun and Dieter Rams, one of the most innovative designers of the previous century, who was creative director at the firm for over thirty years. In his work for Braun, Rams radically altered the way everyday objects are designed, used and even marketed.

Braun and Dieter Rams

The history of Braun dates back to 1921, when Max Braun, a mechanical engineer, opened a small domestic appliances shop in Frankfurt. The business gradually expanded to include the production of radio components, and then full radio setups. The factories were almost completely destroyed during the war, but Max Braun did not lose heart, and in 1944 he worked hard to rebuild his company.

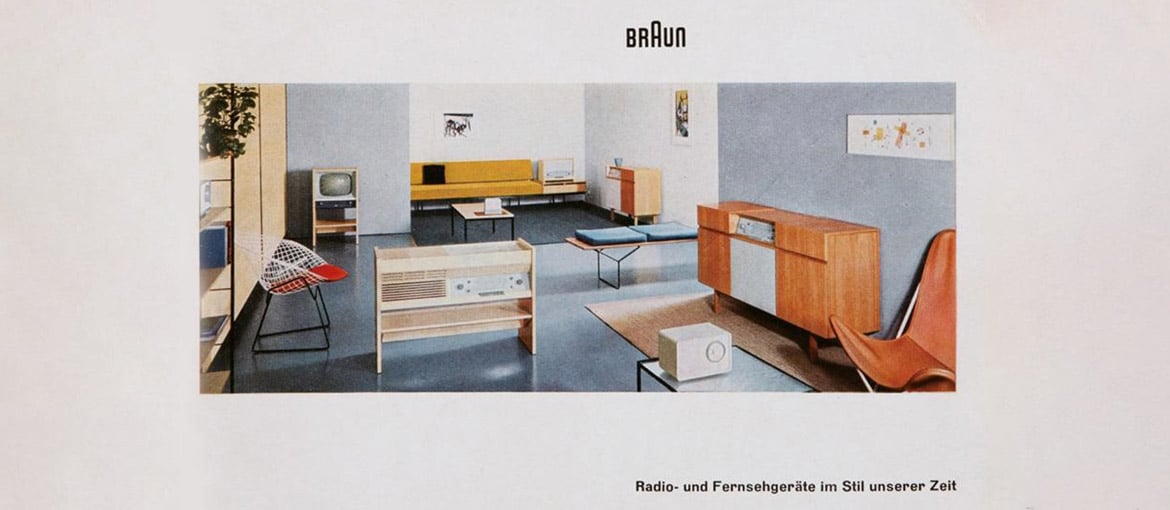

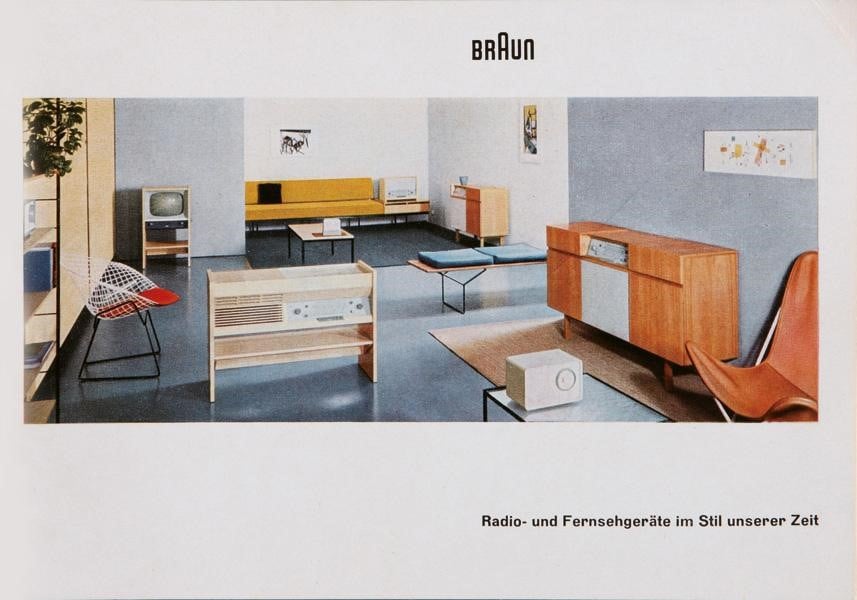

It was in the postwar years that Braun became famous outside Germany, in part thanks to the intuition of his brothers Erwin and Artur, who decided to combine high-level design with engineering techniques and innovative materials. To achieve this, they got in contact with the Ulm School of Design (the successor to the Bauhaus) and hired many of their graduates, with the aim of giving new electronic equipment a practical, efficient and modern look. And it was in this context that the figure of Dieter Rams emerged.

Rams was born in 1932. After working for an architecture studio for a few years, he was recruited by Braun in 1955 as an architect and interior designer, before being promoted to head of design, a position he would hold for over thirty years, from 1961 to 1995.

Rams developed a succinct, elegant and functional style for Braun that was reflected in each of the brand’s products. Simplicity was the key priority, and the design had to clearly demonstrate the object’s function, without any frills or distractions, and always with great visual sense and an obsessive attention to detail.

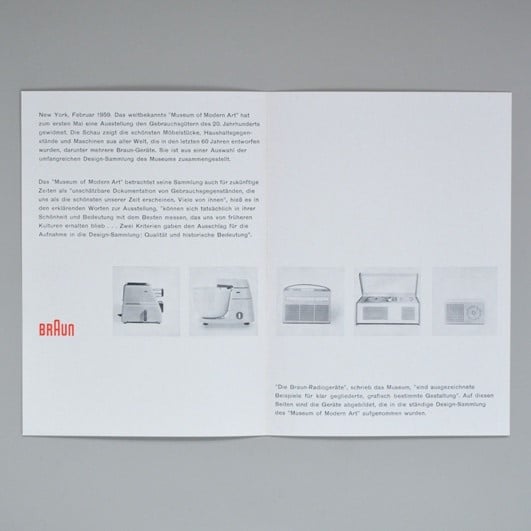

Many of the products that Ram designed for Braun became iconic items that ended up in the collections of leading museums of art and design, including MoMA in New York. However, it is in our homes that the impact of this partnership is most clearly visible today: if you don’t own a Braun product, you are bound to at least have one inspired by the firm.

Braun’s graphic design: pre-empting the minimalism of the modern electronics industry

Rams’s pragmatic and minimalist vision was applied not only to products, but also to the firm’s brand identity, packaging and marketing, under the direction of graphic designer Wolfgang Schmittel, who worked for Braun from 1952 to 1981, and a whole team of top-class designers.

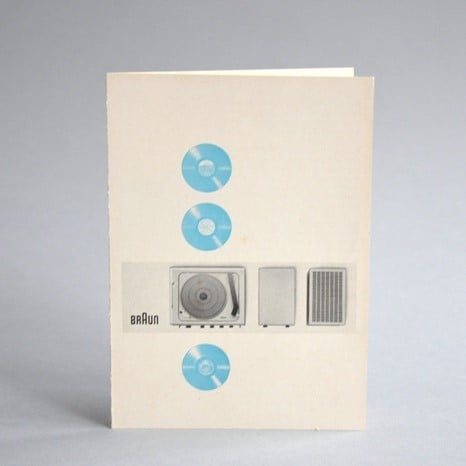

The products and their marketing shared the same objectives: the graphic design had a clean style and exceptional formal quality, describing the product in a direct, unfiltered way.

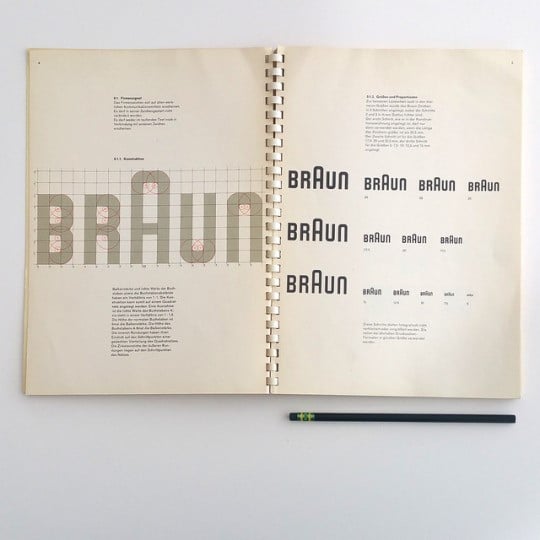

Braun’s first logo, designed by Will Münch, was released back in 1934. The concept of the A sticking out above the other letters is still in use today, although the design has been altered several times, with the first redesign in 1936.

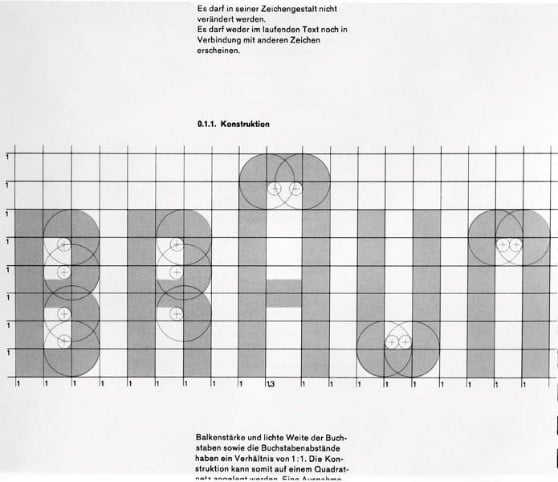

In 1955 the first thing Schmittel did was rework the logo again. He remained faithful to the basic concept, but created a more rational construction, giving the logo a solid and succinct appearance, easily readable in any size and in any context. Schmittel understood the importance of ensuring the logo was recognisable, but his work also meant it matched Rams’s vision.

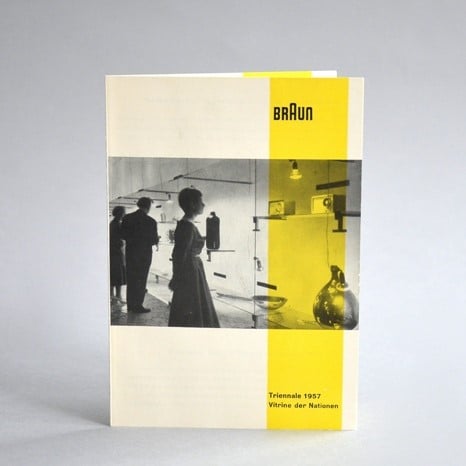

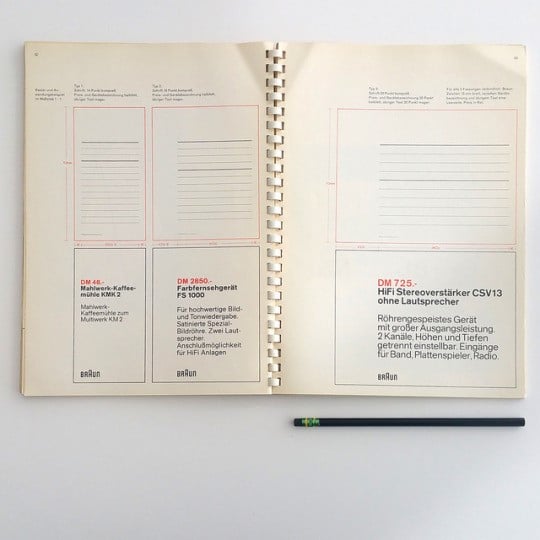

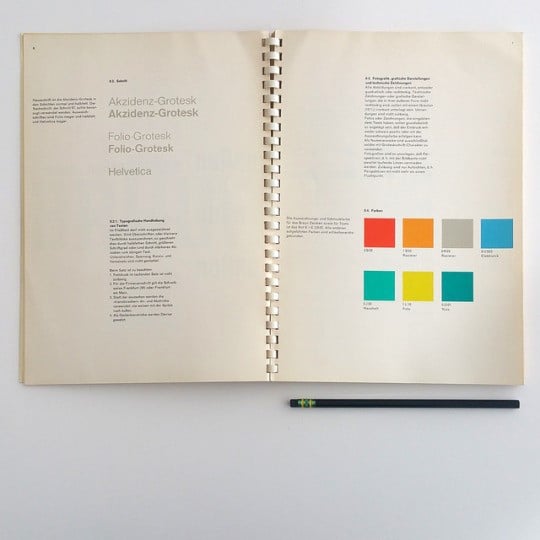

Other elements of the brand identity were defined and formalised at the same time. A pure and austere sans-serif font, Akzidenz-Grotesk, was chosen for use in all contexts, everything from catalogues to adverts. While their competitors used sentimental images and emotional messages to sell their products, Braun developed a new communication model, very much like many technology firms use today: no lies or illusions, just a product presented as honestly and directly as possible, demonstrating its usefulness without the need for metaphors, hyperbole or other rhetorical techniques.

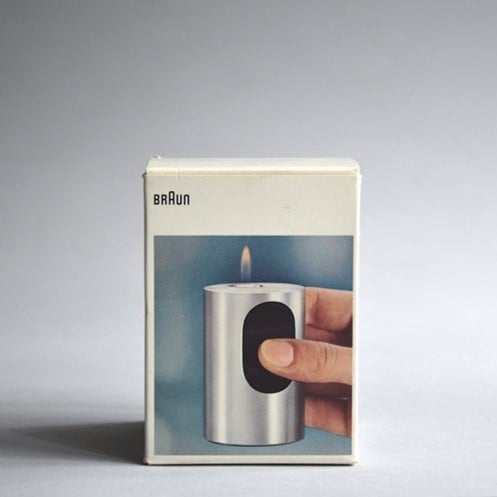

The colour palette was predominantly black and white, but making expert use of touches of bright, bold colours, often in contrast with black and white photographs. As a result, the brand appeared serious and reliable but at the same time not overly mechanical or robotic, with an element of humour, warmth and humanity.

The photography employed by the firm was not left to chance either. Whether black and white or colour, it always presented the product clearly, with excellent lighting. Once again, there was no need for any sentimentality: a product, if well shot, can speak for itself.

In the late 1950s, Braun’s photographers were two women, Marlene Schnelle and Ingeborg Kracht; the latter later became Dieter Rams’s wife.

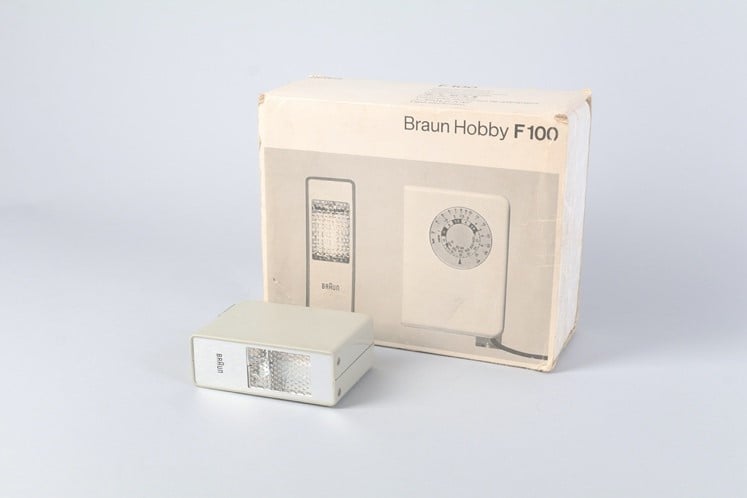

The principles we just described can also be seen in the products’ packaging, which was extremely innovative in its simplicity and clean style. It is immediately apparent how much the packaging of modern tech products has been influenced by ideas originally instigated by Braun.

Schmittel believed it was crucial to ensure the branding was consistent everywhere, despite the growing size of the company. With this in mind, brand guidelines were produced and distributed to every member of the marketing department. In an era when brand manuals were not yet the norm, Schmittel, under Rams’s watchful eye, created an extremely sophisticated and detailed example of one, which would inspire subsequent generations of designers (including Massimo Vignelli, who kept a copy in his personal archive).

Legacy

The extraordinary legacy left by Rams and his colleagues at Braun on the world of design and technology has been recounted numerous times in exhibitions, catalogues, documentaries and archives. The documentary Rams paints a portrait of the designer, but also reflects on consumerism, sustainability and the future of design.

Less and More: The Design Ethos of Dieter Rams is the catalogue from an exhibition held in Osaka, London and Frankfurt. While focusing predominantly on Rams, it does not forget the other designers he collaborated with at Braun, and offers an excellent overview of the company’s visual communication.

On the same note, another essential resource is Das Programm, a research programme directed by Dr Peter Kapos, that studies and promotes activities relating to Braun’s design under Rams’s leadership from 1955 to 1995. Their website also serves as a precious digital archive.

If you’re still not convinced about the influence Braun’s design has had on the world, have a rummage around in the attic for an old iPod or open the calculator on your iPhone. The fact that you have that object or app in your hands, and the form it takes, is in part thanks to Dieter Rams…