Table of Contents

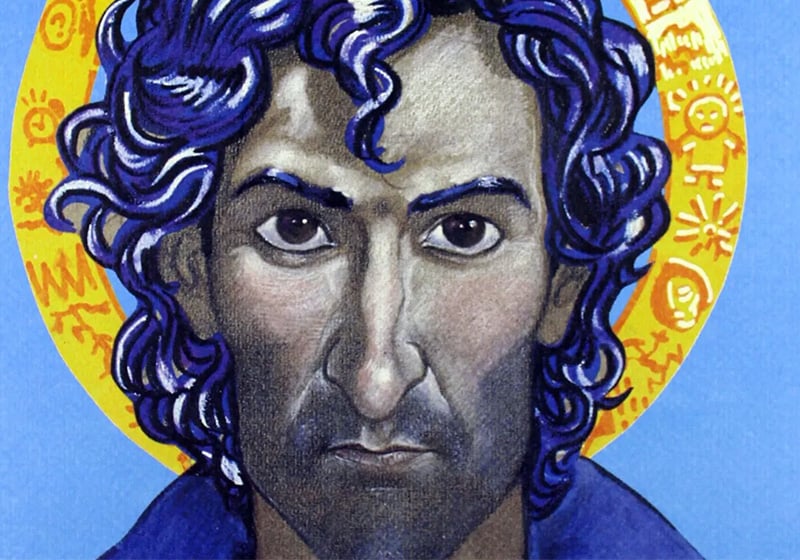

Masters of comics: Andrea Pazienza

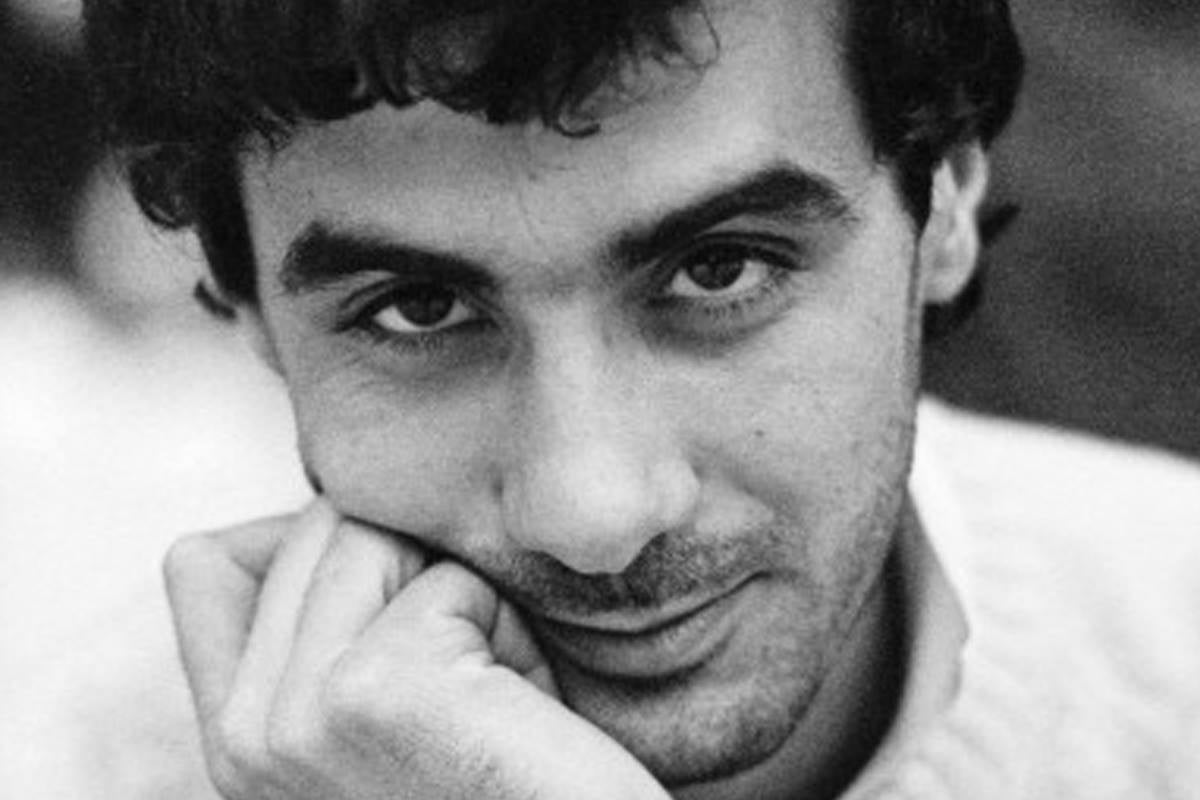

Andrea Pazienza was born in San Benedetto del Tronto on 23 May 1956. His parents were teachers: his father taught art and his mother technical drawing. He spent his early years in San Severo, near Foggia. From a young age, he showed a great interest in drawing: according to his parents, at just 18 months he was already drawing extremely realistic animals.

At the age of 12, Pazienza moved to Pescara for his studies and quickly began moving in local artistic circles, even becoming a co-owner of the “Convergenze” art gallery. It was here that he got to know artists and intellectuals, including Tanino Liberatore, a key figure who would become a life-long friend. In 1974, he began an art degree at the University of Bologna, but didn’t finish it because he immediately began working as an artist. His only missing module was aesthetics, taught by none other than Umberto Eco, but Pazienza didn’t feel up to taking the final exam (despite having befriended Eco).

Pazienza held his first show in Pescara in 1975. It was a series of paintings that stunned visitors and included Isa d’estate, dedicated to dear friend Isabella Damiani, which was recognised as a genuine masterpiece. Indeed, Andrea Pazienza was not just a master of comics, but a much-admired artist: his unique colourful and dreamy style would influence many artists over the coming years.

Pazienza had a love-hate relationship with the city of Bologna: the university milieu, militant politics, piazzas and demonstrations became the backdrop for the first stories by Paz, as he would also be known. It was here that he soaked up many of the themes that would later feature in his work. These included the post ‘68 era that culminated in the protest movement at the end of the 70s. But the year that he would make his name among the wider Italian public was 1977.

The debut with Pentothal

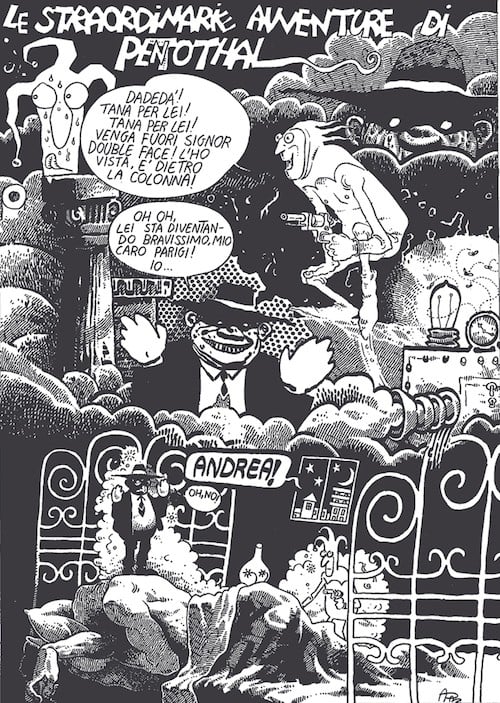

Andrea Pazienza’s real debut, that is to say proper paid work as a comic artist, came in 1977 on the pages of Alter Alter, the magazine founded by renowned Italian author and dramatist Oreste del Buono. Pazienza submitted a 10-page story entitled “The Extraordinary Adventures of Pentothal”, which blew people away with its drawing and storytelling.

Pentothal is a reference to the drug widely portrayed as a truth serum in popular culture. And The Extraordinary Adventures of Pentothal, which was serialised in Alter Alter between 1977 and 1981, was in fact a confession by the artist. It’s an intergenerational piece that tells story of a young man trapped in a reality from which he can’t escape.

The style is fluid, evolving year after year. Paz’s technical skills are outstanding, showing great narrative craft with stories inspired by the anxieties and mental journeys that went hand in hand with the unrest that struck Bologna in 1977. These were the years of so-called “self-managed social centres”, counter-information and huge street demonstrations. And in 1977, an event occurred that would be a watershed in the artist’s life.

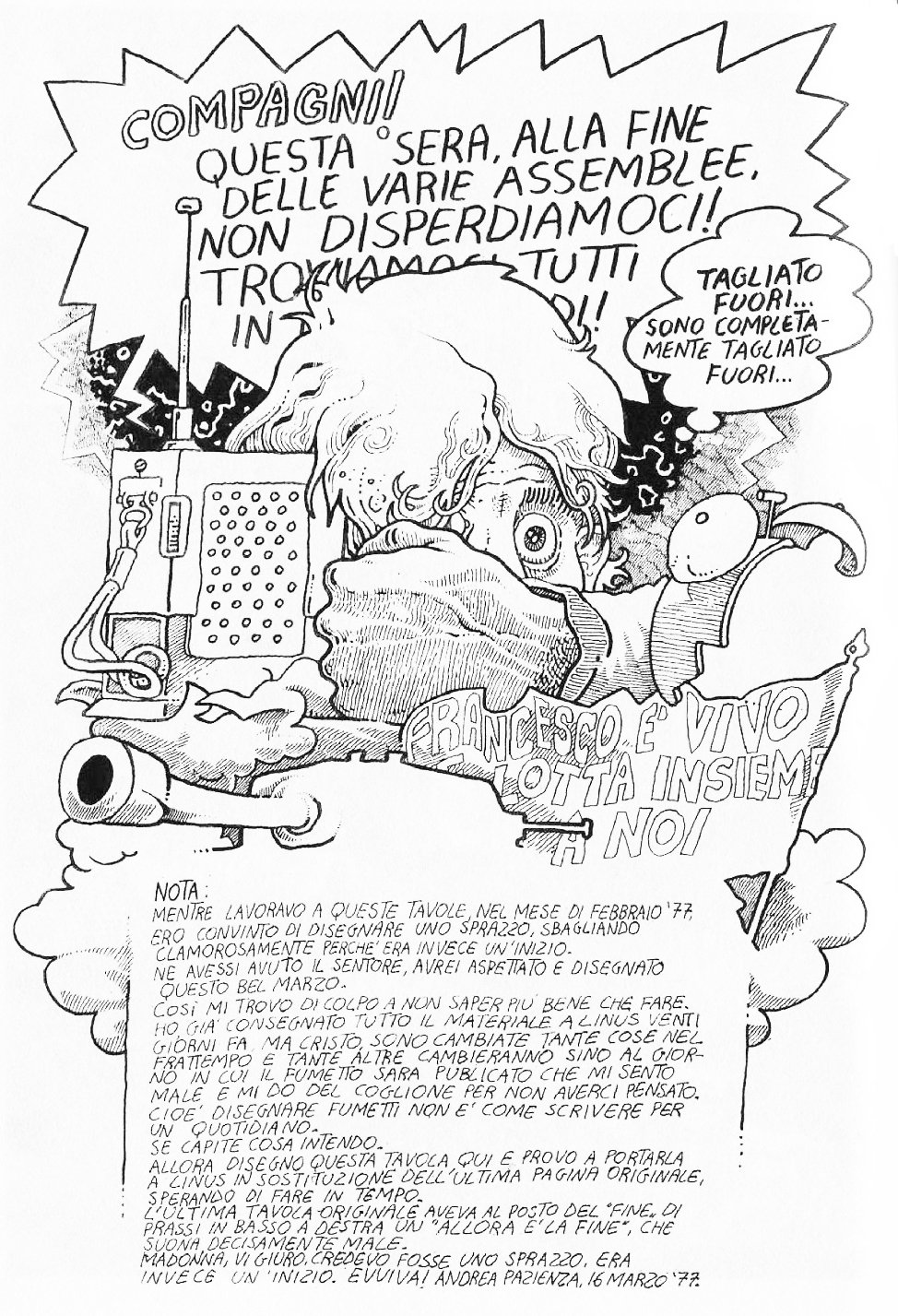

Francesco Lorusso, a young far-left militant, was killed by police during unrest at the University of Bologna. On learning of this tragedy, Pazienza ran to where Alter Alter was printed and, at the very last minute, gave them a completely redesigned final page for Pentothal to replace the existing one.

In it, we see the change that has occurred inside the artist: he speaks directly to the reader, breaking the fourth wall and sparking a revolution in comics without even realising it.

With Pentothal, Pazienza had shown himself to be a mature artist: he managed to shift readers’ attention from the characters to the artist himself. It was a crucial change at the time, when comics were still known and bought for their characters. Pazienza elevated the status of those behind the drawing board to that enjoyed by novelists. At last, comics were no longer just for kids.

From magazines to Zanardi

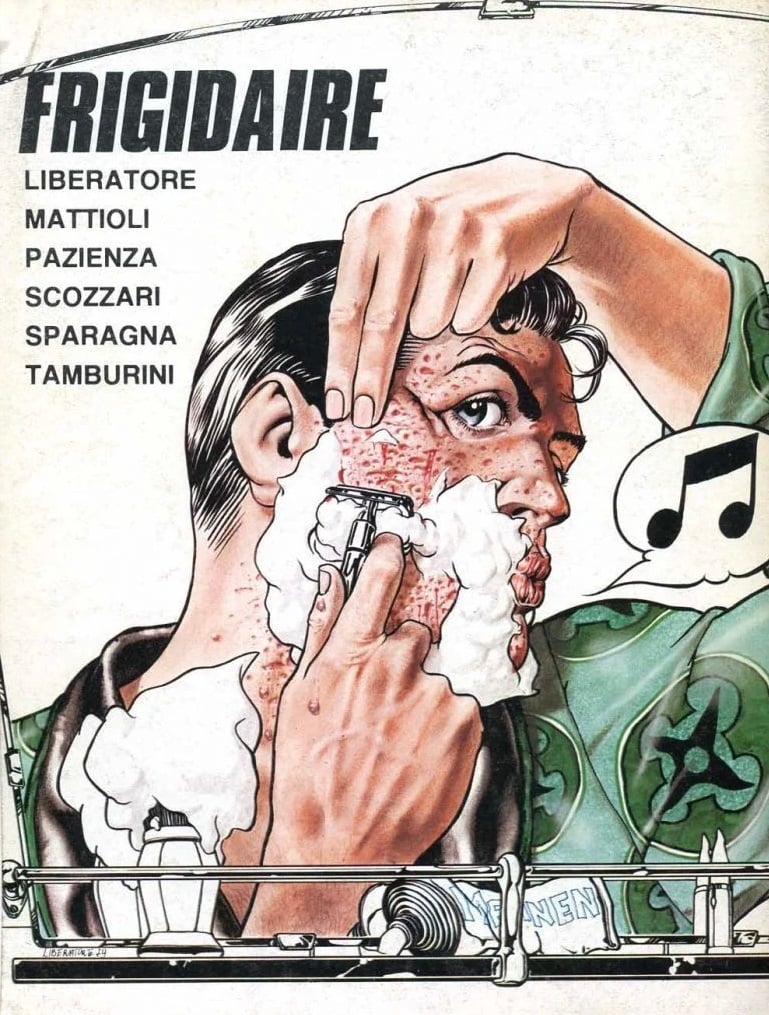

During Pazienza’s Bologna years, Italy’s iconic comic magazines, which are no longer around today, were still going strong. These were often independent magazines that carried comic stories, published in episodes, created by different authors, as well as journalistic investigations and much more. Pazienza worked for Cannibale – founded by Stefano Tamburini and Massimo Mattioli in that fateful 1977 – together with friends Filippo Scòzzari and Tanino Liberatore. This close-knit group would go on to work together on magazines including Il Male, Corto Maltese and Frigidaire.

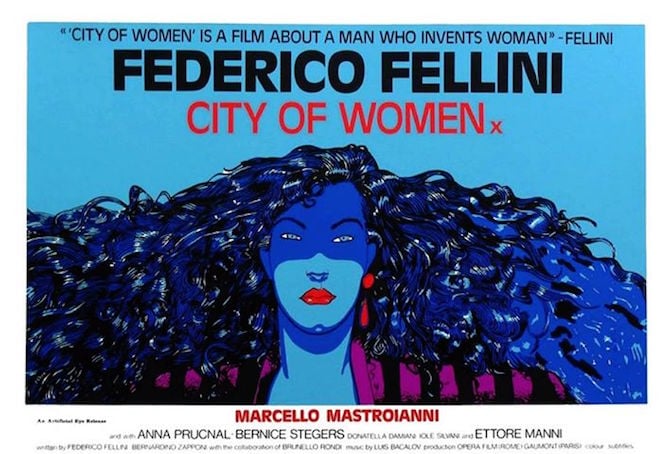

From 1978 onwards, Andrea Pazienza became a rockstar of the comic book world: he drew album covers for musicians Roberto Vecchioni and PFM, as well as the posters for Federico Fellini’s “City of Women” and Bernardo Bertolucci’s “1900”.

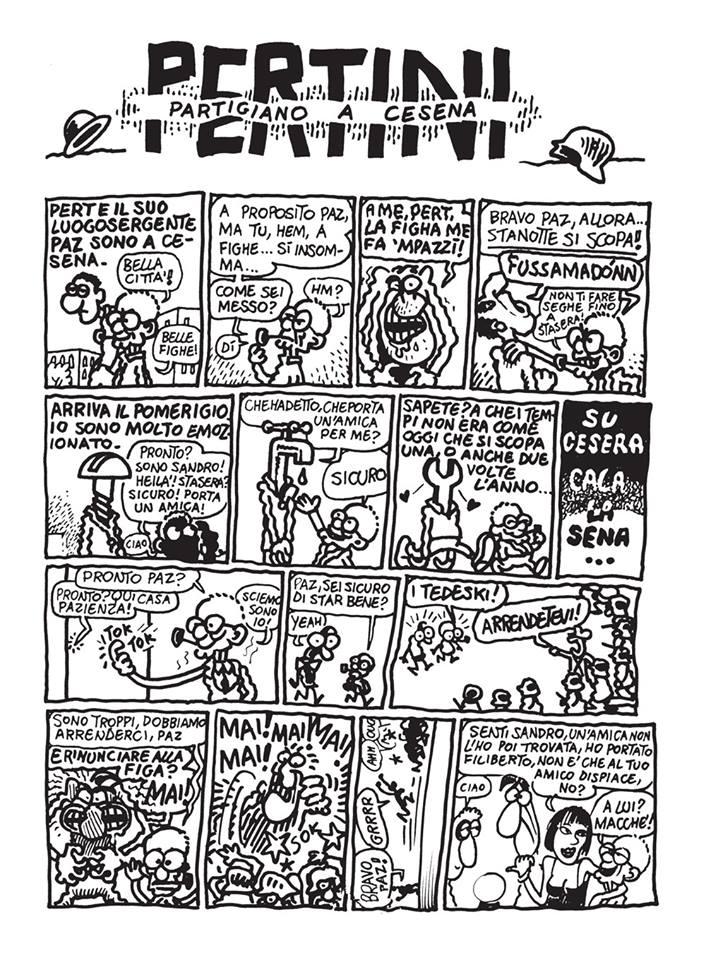

This was also a period of experimentation and satire, including a series of cartoons featuring then president of Italy, Sandro Pertini, which were published in all the magazines Pazienza worked with, from Il Male to Frigidaire and Cannibale. Pazienza was fascinated by Pertini and his moral integrity, so much so that he created a series called “Pertini the Partisan”, in which the president (jokingly called “Pert” by Pazienza) was accompanied by a young “Paz” as his right-hand man, giving us the ridiculous duo “Pert and Paz”.

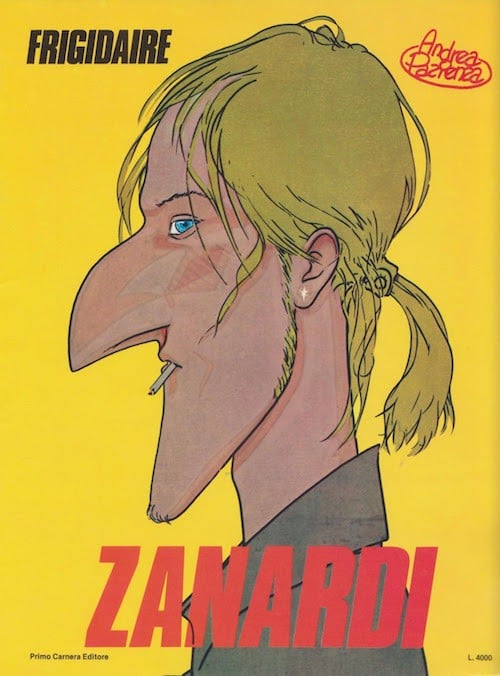

In subsequent years, however, we saw an Andrea Pazienza increasingly worried about the world. Out of this came his second iconic character: Zanardi, his sad and angry alter ego.

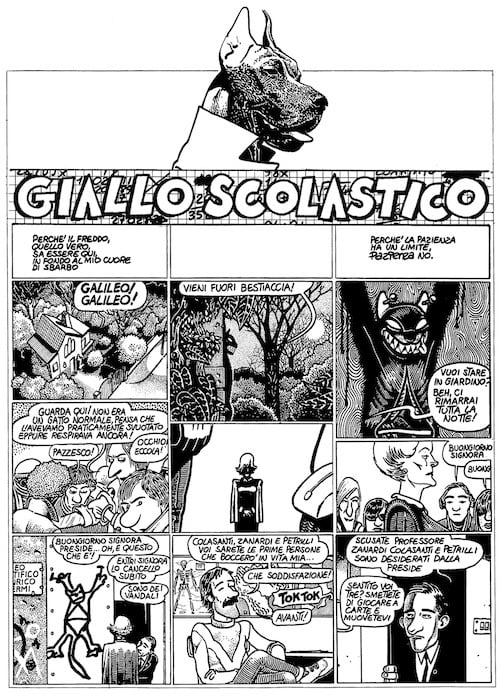

Appearing for the first time in “Giallo Scolastico” in a 1981 issue of Frigidaire, it was the character that really brought Pazienza to fame. The mass movements of 1968 and 1977 were giving way to the hedonism, drugs, money and individualism of the 1980s. And this was reflected in a morally depraved character, who, alongside his trusty sidekicks, was dedicated to pulling the cruellest pranks and taking every drug he can get his hands on.

Always accompanied partners in crime Colasanti and Petrilli, Zanardi is an anarchic and obnoxious sixth-form student who perfectly embodies nihilistic rebellion against any type of so-called respectability. Pazienza described Zanardi thus: “His main character trait is shallowness. A complete shallowness that permeates everything his does”.

At this point, Pazienza’s influence on Italian comics and popular culture was unstoppable. His popularity was exploding and he was collaborating on many new projects. He worked on Avaj, founded together with Jacopo Fo, and then taught comic arts the Libera Università di Alcatraz, set up by Dario Fo at Santa Cristina, near Gubbio. In Bologna, meanwhile, the “Zio Feininger” comic art school was established. Pazienza taught here too, alongside Igort, Magnus, Lorenzo Mattotti and many more major artists from both Italy and abroad.

These were prolific years for Pazienza, which saw him branch out into screenplays, theatre and advertising design. But heroin – the drug that would eventually kill him – had also become a part of his life.

Pompeo, his semi-autobiographical graphic novel

In 1984, Andrea Pazienza moved from Bologna to Montepulciano, Tuscany, but continued travelling around Italy for work and even started contributing to renowned magazine Linus. In June 1985, in Rome, he met Marina Comandini, who became his wife in 1986 and moved to Tuscany with him.

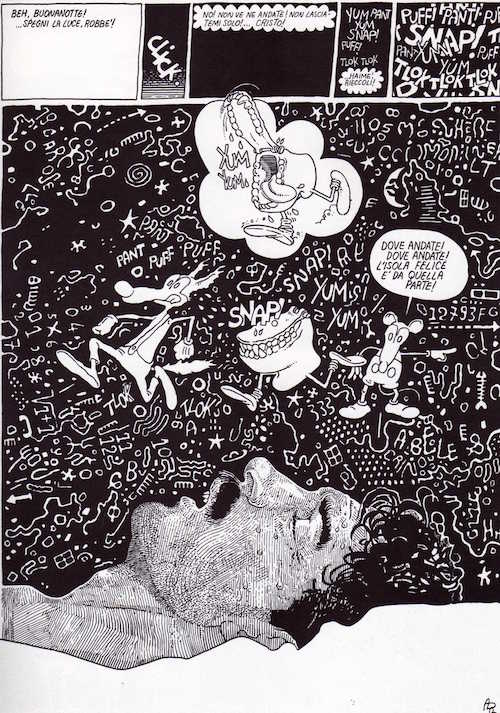

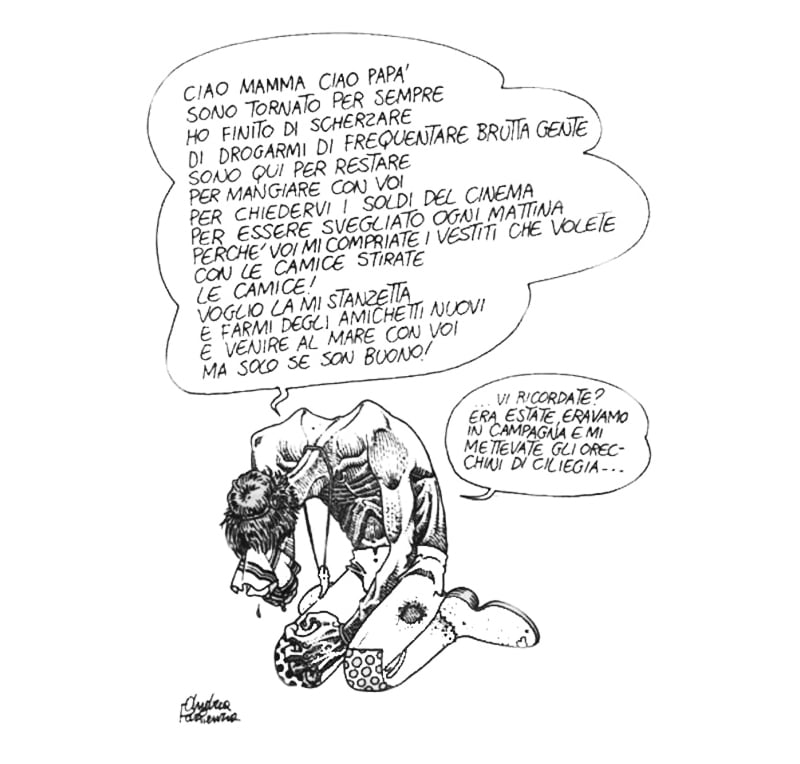

It was here that he created one of his most iconic characters in Pompeo, which was published by Editori del Glifo at the end of 1987. What today we would call a graphic novel, it is in many ways an autobiographical story of a spiral into heroin addiction with nods Pazienza’s past work. It is an introspective piece with rich but extremely uneven pen work.

Especially moving and prophetic are the last pages showing “The last days of Pompeo” in which Pazienza undertakes a sort of final introspection that foreshadows his own death.

On 16 June 1988 in Montepulciano, Andrea Pazienza died of a heroin overdose. Yet dependence was never what characterised the work of one of Italy’s greatest ever artists. His exuberant and uneven style, his flexibility in storytelling both in comic strips and more complex formats, and his ability to effortlessly move from one medium to another made Pazienza an extremely rare artist who revolutionised comics and inspired hundreds of artists in the decades after his death.