There’s a famous little town in the province of Salerno, Italy, with a shade over 5000 inhabitants: it’s Amalfi, a beautiful corner of the world nestled between the Valle dei Mulini (Valley of the Mills) and the sea, a place full of stunning views and, of course, tourists. Amalfi was a maritime republic renowned the world over not just as a trading powerhouse, but also as a leader in paper making.

Paper was invented in China in the first century AD and reached Amalfi just as the republic was establishing trading relations with the Arabs. From the Arabs, the Amalfitans learnt various techniques for making paper, which became known as Charta Bambagina, some say after the city of El Mambig, others after the eponymous cotton used to make it. At one point, in the city of Amalfi there were 16 paper mills dotted along a street below which the River Canneto ran.

Amalfi paper is world-renowned for its extra-fine quality: it was initially used for private correspondence and legal documents throughout southern Italy by the houses of Anjou, Aragon and Bourbon, and by Naples’ Spanish Viceroys. Word of the paper’s quality soon spread overseas, and foreigners began flocking to Amalfi specifically to print their work on its paper. Today, Amalfi paper is still used for a variety of purposes, from watercolour drawing to ceremonial invitations and more.

We saw how paper can be made by hand today, as it was centuries ago.

Thanks to a descendant of an old family of papermakers, Nicola Milano, Amalfi has its own paper museum, which lies in the aptly named Via delle Cartiere (Paper Mill Street). The museum is housed in a former paper mill, dating to sometime between the mid-13th and the 14th century, which was donated to a charitable trust that has managed it since 1969.

We paid a visit and were amazed to discover that it contains fully functioning machines from the period, including the mill, as was explained to us by director Emilio De Simone, who has run the museum for almost 20 years: “We try to preserve this rarity and tradition, this Amalfi excellence. In fact, it’s the only paper mill in Europe where original machinery is still functioning, and we provide a chance to see it at work”.

The museum shows the functioning of a variety of technologies used to produce paper in centuries past. The machinery is powered by water from the nearby River Canneto. This is a genuine paper mill which also serves as a museum (with guides in various languages), housing machinery dating back to the 1700s that is used for making paper by hand. So, what is the ancient process adopted to make such top-notch quality paper? Today, of course, production processes are technologically advanced (see our in-depth look at Fedrigoni) but it was fascinating to watch, in 2018, paper being made by hand using 400-year-old machinery.

How to make paper by hand: the demonstration

What sets Amalfi paper apart is the distinctive production process, which doesn’t use cellulose obtained from wood. Essential to the process is a pulp that, when diluted with water, can be used to make paper. Instead of cellulose, the “ingredients” are white linen, cotton and hemp rags. In the past, these rags were pulped in a machine called a hammer mill, which consisted of a battery of spiked hammers: it was powered by water, and wind was then used to dry the paper. We saw this in action too.

The pulping process continued with the cleaning and further breaking down of the cloth to isolate any sprouting or threaded fibres which would ruin the machines and compromise the quality of the product. Then came garnetting, a procedure which reduced woven fabric to its constituent fibres, leaving the latter intact.

After further cleaning, a fibrous mass was obtained, called the “half-stuff”. This contrasted with the “whole stuff”, the refined material obtained by beating and grinding the pulp with large wooden hammers in stone basins.

The end result was a pulp which, when diluted with water, was ready for making paper.

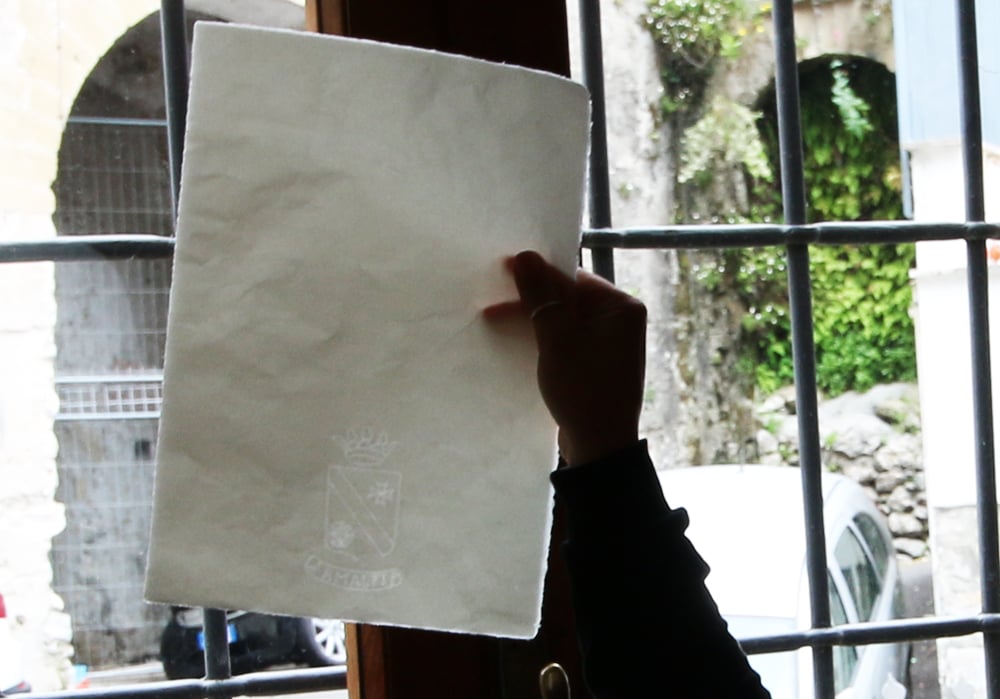

Dissolved with water in a vat, the fibre was then made into sheets by hand, using frames made of cotton and bronze threads, and which carried the watermarks of the city’s noble families. In the vat, the papermaker would immerse a special frame covered in a metallic mesh and scoop up an amount of pulp which was then spread in a mould and drained of water to leave a thin layer of material.

The sheet of paper was then laid on a felt pad and covered with another felt pad.

The sheets were then pressed to eliminate any residual water.

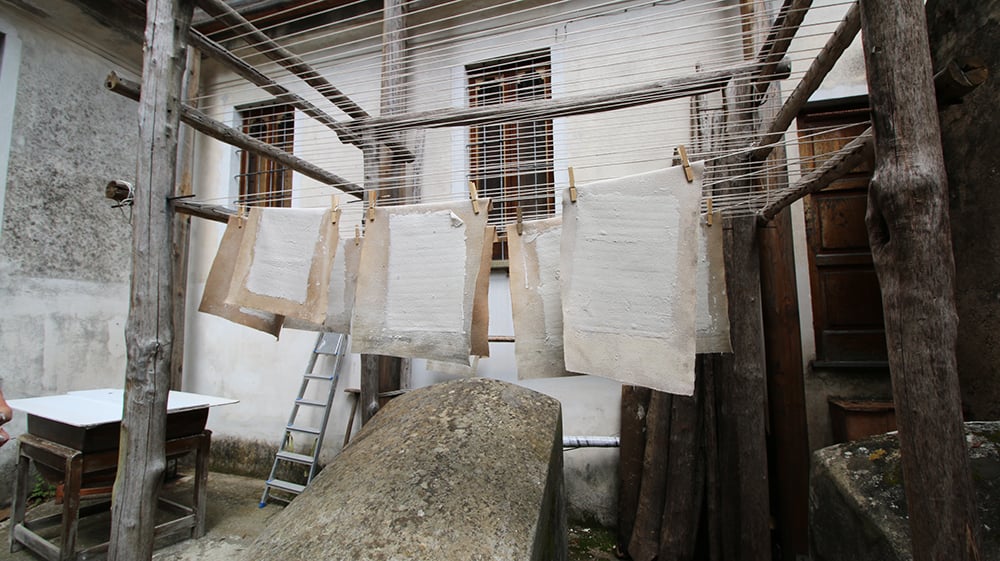

The last stage in the process involved leaving the paper to dry on special racks.

In Amalfi, the hammer mill was replaced by the Hollander beater in the mid-1700s. As well as for refining, this machine was also used for washing and garnetting. The device consisted of a stone and cement basin with a wall down the middle dividing it into two channels. In the wider channel, known as the working channel, spun a cylinder fitted with paddles.

The Hollander beater was more productive because it sped up the process, thus reducing costs. When the basin was filled with rags, clean water was poured in. Insoluble impurities like sand dropped down to the bottom and the process was considered complete when the waste water coming out of the machine was clear. Next came garnetting, when the rags were passed through the blades to break down any remaining traces of fabric, leaving a fibrous mass. At this point, the pulp was sufficiently homogenous and fibrous to be fed through a Fourdrinier machine to be rolled out.

This machine turned the “whole stuff” into actual sheets of paper. Finally, the paper was pressed between two big copper cylinders.

Once you’ve finished this fascinating visit, you can find out more in the library dedicated to papermaker Nicola Milano, the museum’s founder. It contains some 3,520 volumes, including foreign publications, covering everything from the latest technology to the history of the paper industry.

An absorbing adventure into the world of traditional paper-making using technologies that focus on recycled materials and quality.