Table of Contents

The life and work of Alberto Breccia, a master of black and white comics and one of the greatest exponents of Argentine historieta.

Contents

- Masters of comics: Alberto Breccia

- Scraping a living as a cartoonist

- Working with Oesterheld: Mort Cinder, Life of Che and the Eternaut

- The 70s and 80s: the collaboration with Trillo and Perramus

- The legacy of Alberto Breccia

Born in Montevideo, Uruguay, on 15 April 1919, Alberto Breccia is widely considered one of the greatest masters of comics. He inspired and continues to inspire hundreds of comic book artists with his expressionist aesthetic, striking use of black and white, experimentation with unconventional tools and innate ability to span different genres and styles.

To truly grasp the significance of his life and work, it’s essential to understand the political context in Argentina from the 1930s onwards, which had a huge impact on the stories that he illustrated and the writers he worked with.

In 1930, there was a violent military coup, which ushered in a decades-long period of coups, dictators and revolutions which lasted until the start of the1980s. During this time, civil and constitutional rights were practically non-existent: anybody could be considered a political dissident (and be imprisoned or worse). This is the context in which Breccia worked for much of his extraordinary career.

Scraping a living as a cartoonist

Alberto Breccia moved to Buenos Aires with this family at the age of three. He began publishing his work from the age of 17: at the time, he worked as a warehouseman for a firm that refrigerated meat. His earliest work was short strips for newspapers and magazines like TitBits Magazine, El Gorion and Rataplan, for which he drew horror and science fiction stories, as well as comic book adaptations of stories by Edgar Allan Poe.

“I started drawing to escape the awful work that I had to do to earn a living. I was paid very little for these comics. I think I earned about enough to buy a handkerchief to dry my tears!”, he once joked in a documentary about his life and work.

But his work for these magazines opened doors. In 1945 he became an illustrator for Patoruzito magazine, producing the drawings for his first long story, Jean de la Martinica, and then Vito Nervio, a sort of Argentine James Bond. That same year, his first son was born, Enrique Breccia. Enrique would follow in his father’s footsteps and the pair later worked together on various projects.

Over the next decade, Breccia continued to develop his own distinctive style, which showed clear influences of American artists like Alex Raymond, Milton Caniff and Burne Hogarth. His signature expressionist tones started to shine through, and his graphic and narrative experiments began in earnest.

Working with Oesterheld: Mort Cinder, Life of Che and The Eternaut

As well as illustrating various children’s books, Breccia looked increasingly towards the European comic book market. Key to this shift in focus was an encounter with Hugo Pratt, the celebrated creator of Corto Maltese.

Pratt had a profound influence Breccia’s change in approach to his work: “We were walking around Palermo, talking about our work and Pratt said to me: ‘you’re producing shit and you can do better’. I was angry and I’d almost given up drawing. I didn’t speak to him for a long time, but slowly I realised that he was right”, he said (the subsequent improvements were plain for all to see).

Again thanks to Pratt, Breccia met the writer and political activist Hector German Oesterheld in 1950. Both we’re deeply unhappy with the trivial themes tackled in the pages of the popular magazines that published their work. The comic book, or historieta as it was called in South America, had the potential to address weightier issues. So Oesterheld decided to found his own publishing house, Frontera Editorial.

One of Frontera Editorial’s seminal publications was the magazine Hora Cero in whose pages appeared Sherlock Time, a space-travelling detective. Breccia illustrated this science-fiction story and in it we can see the evolution of his style, with big backgrounds and the expert use of white to convey light.

Undoubtedly a major influence was the Argentine dictatorship in which both authors lived: there was the ever-present threat of being labelled as subversives, so all of Oesterheld’s stories and Breccia’s drawings refer to power and society indirectly through metaphor and allegory. This gave the stories multiple layers of meaning that were illustrated with Breccia’s lunar drawings.

After leaving Argentina and working for Fleetway Publications in the UK, Breccia was forced to return home in 1961 to care for his gravely ill wife. While his spouse was slowly losing her fight for life in the next room, Breccia drew the Mort Cinder series, which was also written by Oesterheld, and published in 1962 in Misterix magazine.

Mort Cinder consists of ten series of stories published over two years. The main character, Mort Cinder, is practically immortal: whenever he seemingly dies, he comes back to life again. Cinder is a space and time traveller who lives in various times and places, from the Tower of Babbel to the Battle of Thermopylae to the First World War. Condemned to eternal suffering, he witnesses event after historical event, bringing readers first-hand accounts of the people who were there. Cinder is accompanied by his right-hand man Ezra Winston, an antique dealer who bears a striking resemblance to Breccia.

In doing so, they showed how history can be told non-chronologically and unconventionally by literally “deconstructing it”. The influence of Jorge Luis Borges is clear, with episodes presented as a fragment of history experienced at first hand by the characters.

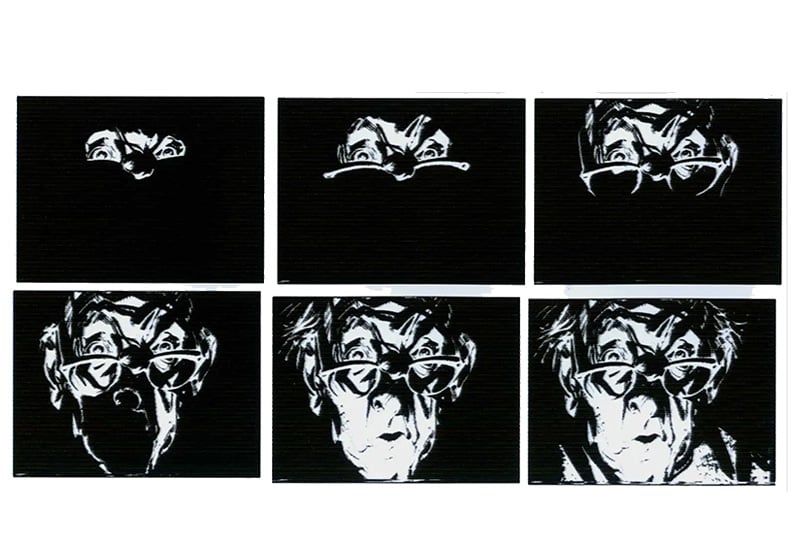

In Mort Cinder, Alberto Breccia’s art evolves further: there are more light effects that dramatise the story, along with new approaches to page composition and visual sequencing. The shadows are more striking and he also experiments with new graphic techniques, using razor blades to bring out whites in darker areas of drawings.

In 1966, he also turned his hand to teaching: together with Hugo Pratt and Arturo del Castillo, he co-founded the Escuela Panamericana de Arte, the first art school in Argentina to teach comic book art alongside other artistic disciplines.

Breccia partnered with Oesterheld again in 1968, doing the penwork for Life of Che, a comic that told the life story of leftist revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara. The project also saw Alberto work together with his son Enrique Breccia for the first time.

It was meant to be the first in a series of biographies about key figures in South American history. However, only one more title was actually published, the story of Eva “Evita” Peron (in 1970), because Argentina’s dictatorship would have dramatic consequences for the project.

Oesterheld and Breccia wanted to tell the life story of someone who was viewed as a symbol of hope and liberation for Latin America. They took an almost journalistic approach, with Breccia creating highly descriptive illustrations that often comprised three big horizontal panels.

In 1969, another Oesterheld/Breccia masterpiece was released: The Eternaut. First published in 1957 in Hora Cero magazine and originally drawn by Francisco Solano López, this science-fiction comic was a smash hit. It tells the story of ordinary people’s resistance to an alien invasion in which the extra-terrestrials use huge snow falls as a weapon of mass destruction against Earth’s inhabitants.

But Oesterheld was not happy with López’s didactic style of visual storytelling, so he re-wrote the comic in 1969 with much more explicit references to the Argentine dictatorship and South America’s geopolitical situation at the time.

While the first version of The Eternaut was written following the overthrow of the Peron regime in a military coup, the new version drawn by Breccia was seen to foreshadow the Argentine coup of 1976 led by Jorge Videla, which would culminate in the so-called dirty war and the dark days of the desaparecidos.

Oesterheld and Breccia’s The Eternaut hit the shelves at time when Oesterheld was very close to left-wing activists: it’s much darker as a result and tells the story of Earth’s inhabitants as they form resistance groups to fight the alien invaders.

The new version had a completely different atmosphere and, despite not achieving the hoped-for success, it remains some of Breccia’s finest work.

Life of Che and The Eternaut marked two enormous milestones in Oesterheld’s growing political consciousness. Tragically, he was arrested and secretly murdered, together with his whole family: he was just one of the thousands of desaparecidos (disappeared) from this dark period in Argentine history.

Life of Che was banned by the regime: Alberto Breccia hid his copies and drafts by burying them in his garden.

The 70s and 80s: the collaboration with Trillo and Perramus

Alberto Breccia continued to work, publishing various pieces for Italian titles such as Corriere dei Piccoli and Corrier Boy, as well as the Squadra Zenith series, which appeared in Corriere dei ragazzi.

He continued his graphical experimentation with The Cthulhu Mythos, adapting the works of Lovecraft for comic books in a series that is notable for the use of diluted ink.

In 1974, Breccia began a collaboration with the writer Carlos Trillo, which resulted in masterpieces like Nadie, Gli occhi e la mente and Chi ha paura delle fiabe, in which his caricatural style leaps of the page.

The pinnacle of Breccia’s career came in 1985 with the publication of Perramus, which won him an award from Amnesty International. Over 700 pages long, this richly allegorical comic book is about a man living under a violent dictatorship and whose job it is to dispose of the bodies of the desaparecidos. It tells the story of his daring escape to freedom: although the main characters are fictitious, they meet real people along the way, such as Jorge Luis Borges, with whom they share this perilous journey.

The legacy of Alberto Breccia

Alberto Breccia is the quintessential master of comics. With his flair for weaving together dark and light, real and unreal, Breccia pushed the boundaries of creativity.

Whether created using brush, pen, blade or sponge, his illustration transformed panels into paintings packed with emotion and tension. His style influenced and will continue to influence not just comic book creators, but the wider world of art.

His legacy lives on in the dozens of artists who have been inspired by his work, as well as the thousands of pages that he drew and painted with such mastery: they are part of humanity’s heritage and stand as a warning about all forms of dictatorship and repression of individual freedom.