Table of Contents

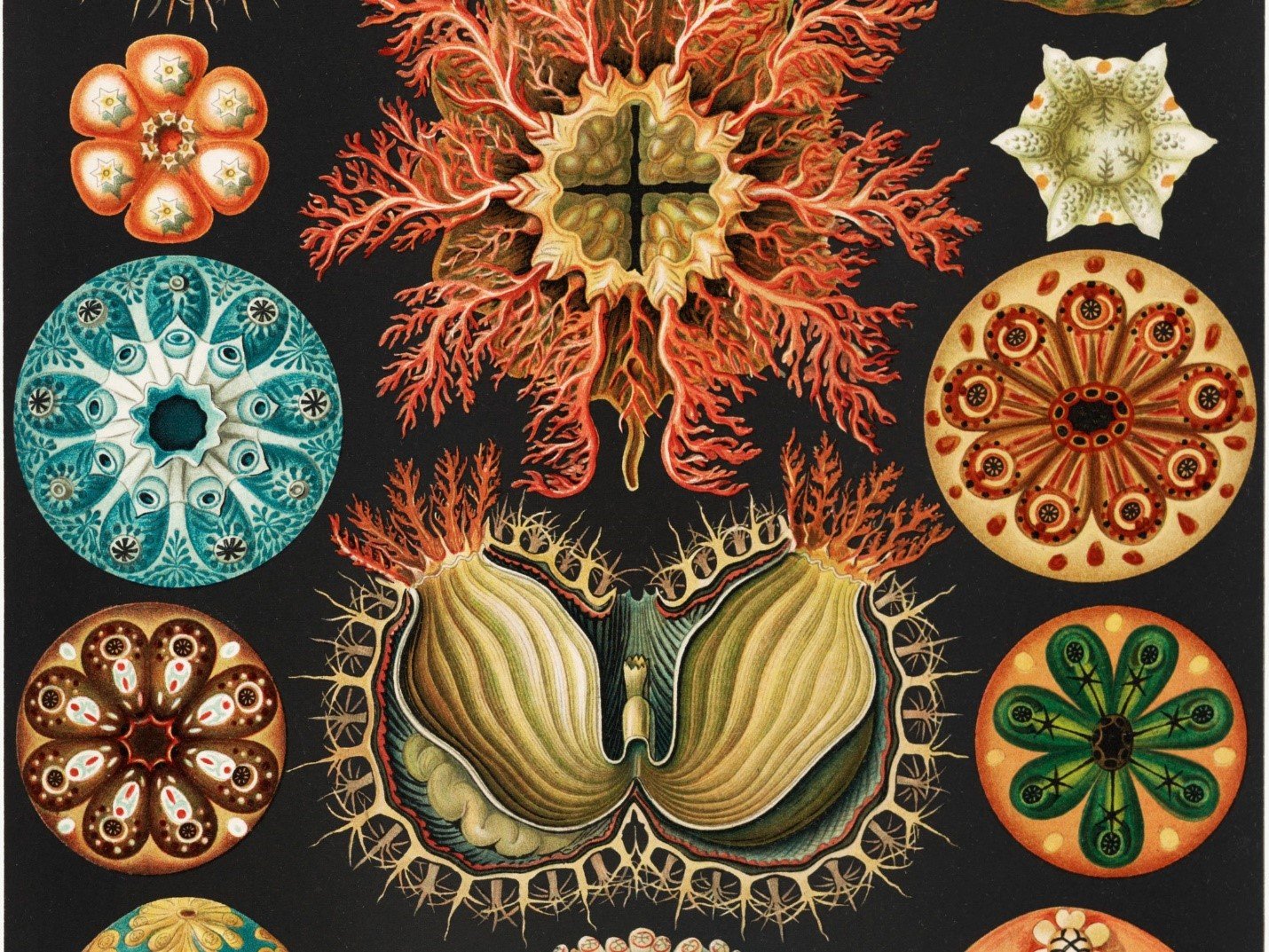

Colourful anemones with meticulous detail; fish and bats depicted in perfect symmetry; voluptuous orchids and microscopic marine creatures with amazing geometric shapes: the biological illustrations published by Ernst Haeckel at the turn of the 20th century are still just as draw dropping today as they were then.

Throughout his life, Ernst Haeckel, an esteemed German scientist, created over a 1000 watercolours and sketches of weird and wonderful plants and animals, some only visible through a microscope, others discovered by the man himself during his research. In 1904, the lithographer Adolf Glitsch printed 100 of them in a volume entitled Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms in Nature). Haeckel’s images quickly spread across the globe and would influence many artists and architects of the era, so much so that they became an inspiration for Art Nouveau.

And yet, just a few decades earlier, Ernst Haeckel was a young, slightly insecure scientist, unsure whether to go into science or follow his passion for art, threatened by his father who feared his artistic leanings, but absolutely enchanted by the beauty of the natural world.

Today we tell the story behind the man, his illustrations and how they became so famous.

Ernst Haeckel – the scientist with the artist’s soul

At the time that Kunstformen der Natur was published, Ernst Haeckel needed no introduction: he was a renowned German scientist, one of the first to popularise Darwin’s ideas in Germany, the discoverer of numerous species and known in academia for having coined various new scientific terms (some of which we still use to this day).

Athletic and enthralled by the natural world, the young Ernst Haeckel was very restless. Forced to study medicine by his father, he decided to become a zoologist so he could indulge his passion for nature. It was during a trip to Italy in search of a scientific project to pursue that he met German poet and painter Hermann Allers. Quickly developing an obsession with art, Ernst stopped his research and began living as an artist. It was only after threats from his father that he returned to his main occupation: he had to find a scientific project so that he could start his career.

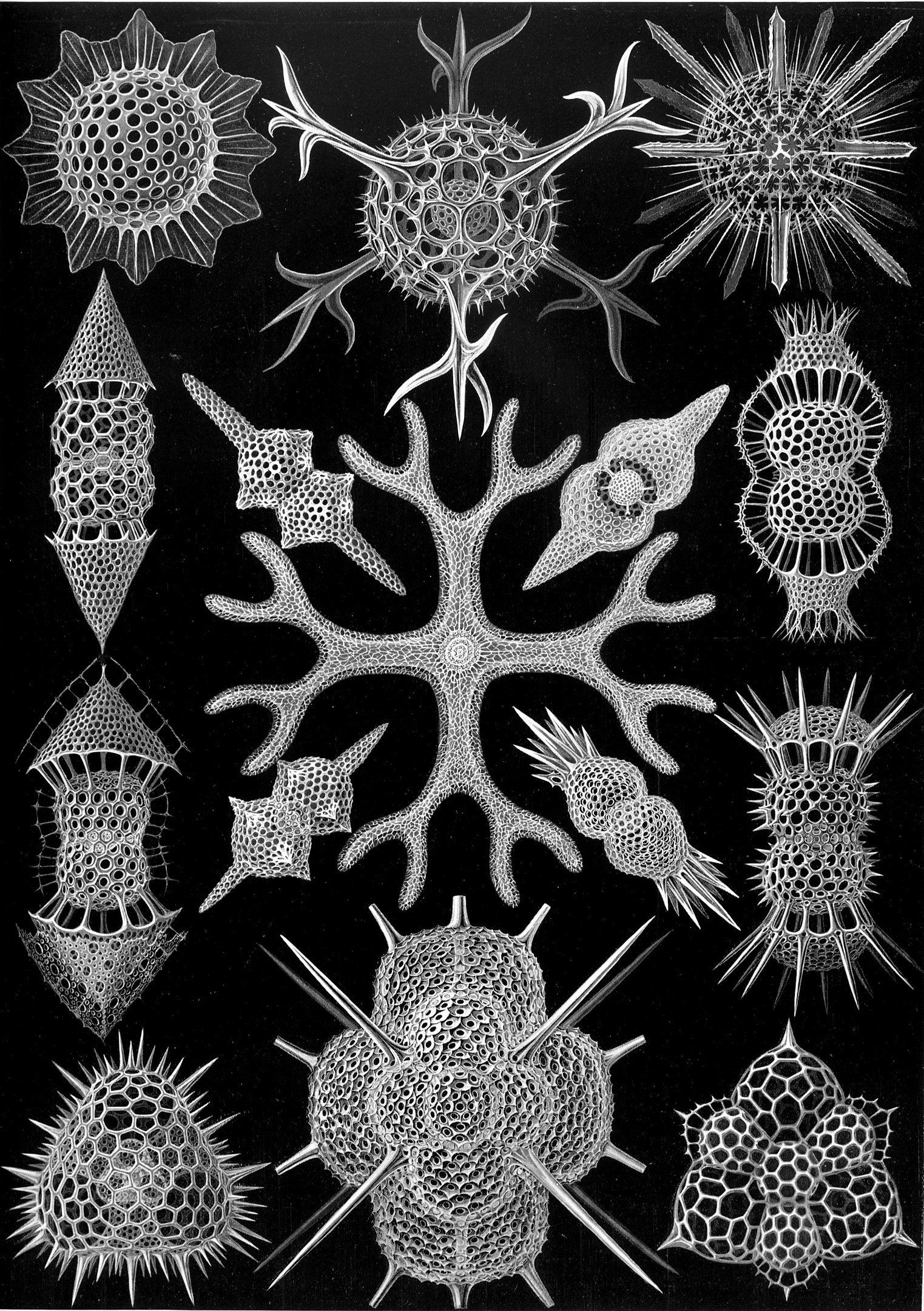

Everything came together a few months later in Messina, when some fishermen brought him buckets of water full of minuscule invertebrates: they were radiolarians, marine organisms that nobody had ever seen before. Haeckel put them under a microscope and discovered their incredible geometric structure.

This research became the project that started his scientific career. But it was much more than that: Ernst Haeckel spent hours and hours looking through the microscope, mesmerised by the beauty of the creatures he had just discovered. And he drew them with painstaking care in his very own artistic style. The conflict between his love of art and scientific ambitions had finally been resolved. Below is a print of Haeckel’s original illustrations of radiolarians.

The influence of Ernst Haeckel’s drawings on Art Nouveau

Almost as if to make peace between Ernst Haeckel’s two souls, his stunning biological illustrations were used by Art Nouveau artists to reconcile an ever more technological and industrial society with nature.

At the end of the 19th century, society was changing rapidly: industrialisation was growing and with it pollution, cities were becoming ever bigger and more chaotic. Art Nouveau artists wanted to reset the relationship between man and nature, so they looked to the natural world to inspire their art, design and architecture.

Many artists from this era, like French designer Émile Gallé, Dutch architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage and French designer René Lalique, kept a copy of Ernst Haeckel’s illustrations at home.

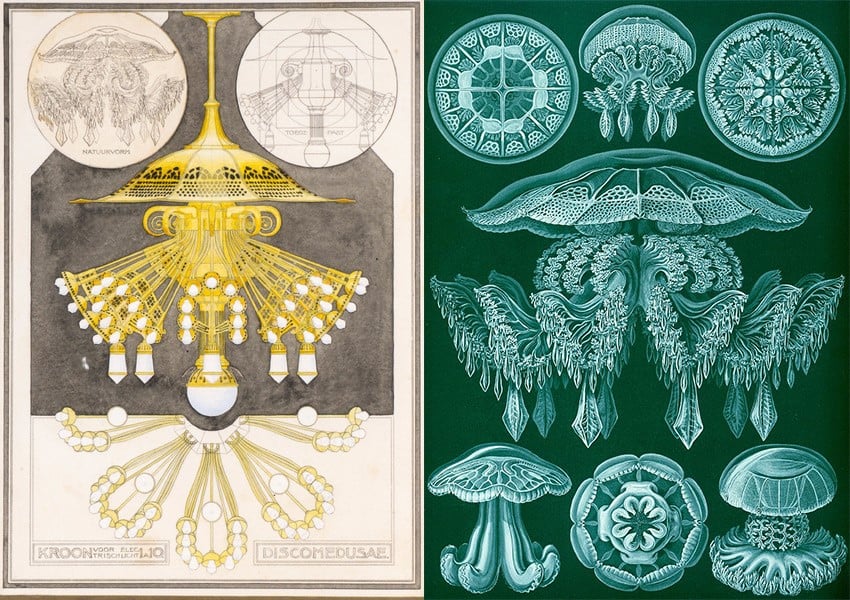

Below, for example, is a decorative chandelier designed by Berlage and inspired by the discomedusa drawn by Ernst Haeckel.

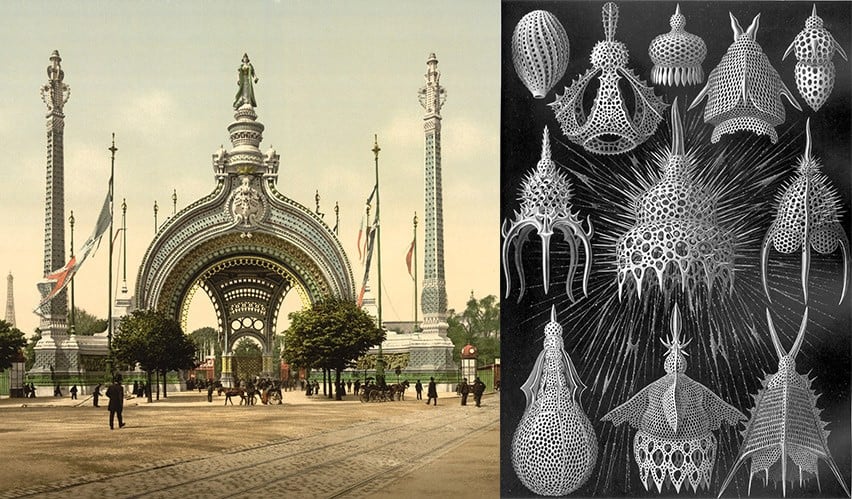

At the 1900 Paris Exposition – the greatest exhibition ever held in France, which was supposed to mark a triumphant start to a century of progress – there were more references to Haeckel’s work. For his ambitious “Porte Monumentale” in full Liberty style, René Binet was inspired by animal and plant shapes, and the railings explicitly borrow elements from the radiolarians drawn by Haeckel.

Even Antoni Gaudì, the famous Catalan modernist architect, used Haeckel’s marine organisms for architectural details such as balustrades and arches, while Louis Sullivan – the father of skyscrapers – had copies of Haeckel’s books, and decorated the facades of his buildings with floral motifs. These and other examples of influences and inspirations are outlined by Andrea Wulf in her book The Invention of Nature, which has a whole chapter dedicated to Haeckel.

The images of Ernst Haeckel – free to download and use

If you too are fascinated by the story of Ernst Haeckel and his biological illustrations, there’s good news. Most prints from Kunstformen der Natur can be downloaded in high definition and used freely as they’re in the public domain. On the Wikipedia page dedicated to Kunstformen der Natur, for example, you’ll find many of the plates have been scanned and are free to download.

All of which means you too can find inspiration in nature’s beauty!